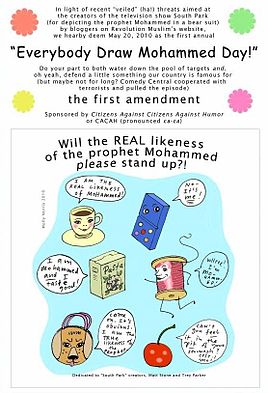

Everybody Draw Mohammed Day

U.S. cartoonist Molly Norris of Seattle, Washington, created the artwork in reaction to Internet death threats that had been made against animators Trey Parker and Matt Stone for depicting Muhammad in an episode of South Park.

[1] Postings on RevolutionMuslim.com (under the pen name Abu Talha al-Amrikee, later identified as Zachary Adam Chesser) had said that Parker and Stone could wind up like Theo van Gogh, a Dutch filmmaker who was stabbed and shot to death.

The group running the website said it was not threatening Parker and Stone, but it also posted the addresses of Comedy Central's New York office and the California production studio where South Park is made.

[18] Bloggers at The Atlantic, Reason, National Review Online and Glenn Reynolds in his "Instapundit" blog, all posted comments and links about the proposed day, giving it wide publicity.

"[30] William Wei of The Business Insider was more critical of the decision by the cartoonist to withdraw from the protest movement, with an article titled, "Artist Who Proposed 'Everybody Draw Mohammed Day!'

"[32] Ron Nurwisah of National Post noted, "Norris' backtracking might be a bit late as the event seems to have taken a life of its own,"[33] and Fox 9 also pointed out, "she may have started something she can't stop.

"[34] Writing for ComicsAlliance, Laura Hudson noted that the website supported the protest movement and would participate in the event on May 20, 2010: "There is power in numbers, and if you're an artist, creator, cartoonist, or basically anyone who would like to exercise your right to free speech in a way that it is actively threatened, that would be the day to do it.

"[36] A columnist for The Washington Post Writers Group wrote that Norris should not be regarded as having further responsibility related to the movement, and affirmed that her Muhammad cartoon had significantly impacted a greater discussion about the issue.

"[41] Gillespie asserted, "Our Draw Mohammed contest is not a frivolous exercise of hip, ironic, hoolarious sacrilege toward a minority religion in the United States (though even that deserves all the protection that the most serioso political commentary commands).

"[51] A representative of the Karachi-based Internet company Creative Chaos named Shakir Husain told The Guardian that a ban of Facebook would not be easy to carry out due to the ability to circumvent it using tactics such as proxy servers.

"[79] The Gabriel Consulting Group analyst Dan Olds commented about the Pakistan government's ban to Computerworld, "I think we can expect to see more of this type of thing coming from dictatorial countries as they try to keep their citizenry locked down.

"[82] Indonesia Communication and Information Minister Tifatul Sembiring stated to The Jakarta Globe, "I consider this an act of provocation to mess up religious harmony enjoyed by Indonesians.

[96] Agence France-Presse noted, "The Pakistan Telecommunications Authority (PTA) extended a ban on Facebook, ordered by a court until May 31, to popular video sharing website YouTube and restricted Wikipedia.

[109] The idea for the May 20 protest received support from Kathleen Parker, an opinion columnist for The Washington Post: "Americans love their free speech and have had enough of those who think they can dictate the limits of that fundamental right.

"[113] Andrew Mellon of Big Journalism wrote in favor of the protest movement, commenting, "The bottom line is that the First Amendment guarantees free speech including criticism of all peoples.

"[115] Writing for The American Spectator, Jeremy Lott commented positively about the protest movement: "While the suits at Comedy Central and Yale University Press have been cowed, people across the country have decided to speak up and thereby magnify the offense a thousandfold.

[117] Law professor and blogger Ann Althouse rejected the Everybody Draw Mohammed Day idea because "depictions of Muhammad offend millions of Muslims who are no part of the violent threats.

"[118] James Taranto, writing in the "Best of the Web Today" column at The Wall Street Journal, also objected to the idea, not only because depicting Mohammed "is inconsiderate of the sensibilities of others", but also because "it defines those others—Muslims—as being outside of our culture, unworthy of the courtesy we readily accord to insiders.

"[119] Bill Walsh of Bedford Minuteman wrote critically of the initiative, which seemed "petulant and childish" to him: "It attempts to battle religious zealotry with rudeness and sacrilege, and we can only wait to see what happens, but I fear it won't be good.

"[121] Writing for New York University's Center for Religion and Media publication, The Revealer, Jeremy F. Walton called the event a "blasphemous faux holiday", which would "only serve to reinforce broader American misunderstandings of Islam and Muslims".

[122] Franz Kruger, writing for the Mail & Guardian, called Everybody Draw Mohammed Day a "silly Facebook initiative" and found "the undertone of a 'clash of civilisations'" in it "disturbing", noting that "it is clear that some feel great satisfaction at what they see as 'sticking it to the Muslims'.

"[123] The Mail & Guardian, which had itself published a controversial cartoon of Mohammed in its pages, distanced itself from the group, noting that it "claimed to be a protest against restrictions on freedom of speech and religious fanaticism, but had seemingly become a forum for venting Islamophobic sentiment.

"[126] In Pakistan, an editorial in Dawn, the country's oldest English-language newspaper, said that there was no doubt that the Facebook initiative "was in poor taste and deserving of strong condemnation," adding that it was "debatable whether freedom of expression should extend to material that is offensive to the sensibilities, traditions and beliefs of religious, ethnic or other communities."

[128] Stephanie Gutmann of The Daily Telegraph wrote that she had joined the Facebook group, and commented that if the 2010 Times Square car bomb attempt was found to be related to the South Park episode "200", "this sort of protest will be more important than ever.

"[132] In an analysis of the protest movement for the Daily Bruin, journalist Jordan Manalastas commented, "Everybody Draw Mohammed Day is a chance to reinstate offense and sincerity to their proper place, freed from terror or silence.

"[133] In an analysis of the protest movement for Spiked, Brendan O'Neill was critical of the concept of "mocking Muhammad," writing, "... these two camps – the Muhammad-knockers and the Muslim offence-takers – are locked in a deadly embrace.

[135] The president of the Association of American Editorial Cartoonists opposed involvement because, "something like that can be too easily co-opted by interest groups who, I suspect, have an agenda that goes beyond a simple defense of free expression.

In the English version of the al-Qaeda magazine Inspire, Al-Awlaki wrote, "The medicine prescribed by the Messenger of Allah is the execution of those involved," and was quoted as saying, The large number of participants makes it easier for us because there are more targets to choose from in addition to the difficulty of the government offering all of them special protection ...

"[140][141][142][143] The threat against Norris appeared to be renewed when Al Qaeda's Inspire included her in its March 2013 edition with eleven others in a pictorial spread entitled "Wanted: Dead or Alive for Crimes Against Islam," and captioned, "Yes We Can: A Bullet A Day Keeps the Infidel Away.

"[144][145] The cartoonist Stéphane "Charb" Charbonnier was also added to Al-Qaeda's most wanted list, along with Lars Vilks and three Jyllands-Posten staff members: Kurt Westergaard, Carsten Juste, and Flemming Rose.