Evolutionary mismatch

In recent times, humans have had a large, rapid, and trackable impact on the environment, thus creating scenarios where it is easier to observe evolutionary mismatch.

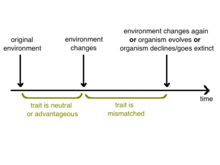

Because evolution is gradual and environmental changes often occur very quickly on a geological scale, there is always a period of "catching-up" as the population evolves to become adapted to the environment.

A coalition of modern scientists and community organizers assembled to found the Evolution Institute in 2008, and in 2011 published a more recent culmination of information on evolutionary mismatch theory in an article by Elisabeth Lloyd, David Sloan Wilson, and Elliott Sober.

This transition quickly and dramatically changed the way that humans interact with the environment, with societies taking up practices of farming and animal husbandry.

In some human societies that now function in a vastly different way from the hunter-gatherer lifestyle, these outdated adaptations now lead to the presence of maladaptive, or mismatched, traits.

This trait serves as the main basis for the "thrifty gene hypothesis", the idea that "feast-or-famine conditions during human evolutionary development naturally selected for people whose bodies were efficient in their use of food calories".

[14] Hunter-gatherers, who used to live under environmental stress, benefit from this trait; there was an uncertainty of when the next meal would be, and they would spend most of their time performing high levels of physical activity.

Fast food combined with decreased physical activity means that the "thrifty gene" that once benefit human predecessors now works against them, causing their bodies to store more fat and leading to higher levels of obesity in the population.

[16] The hygiene hypothesis, a concept initially theorized by immunologists and epidemiologists, has been proved to have a strong connection with evolutionary mismatch through recent studies.

Such environmental conditions favor the development of the inflammatory chronic diseases because human bodies have been selected to adapt to a pathogen-rich environment in the history of evolution.

[19] For example, studies have shown that change in our symbiont community can lead to the disorder of immune homeostasis, which can be used to explain why antibiotic use in early childhood can result in higher asthma risk.

But now, when there are fewer challenges to survival and reproducing, certain activities in the present environment (gambling, drug use, eating) exploit this system, leading to addictive behaviors.

Prehistoric human brains have evolved to assimilate to this particular environment; creating reactions such as anxiety to solve short-term problems.

In summation, traits like anxiety have become outdated as the advancement of society has allowed humans to no longer be under constant threat and instead worry about the future.

Unlike our hunter-gatherer ancestors who lived in small egalitarian societies, the modern work place is large, complex, and hierarchical.

These basic instincts misfire in the modern workplace, causing conflicts at work, burnout, job alienation and poor management practices.

Human ancestors lived in an environment that lacked drug use of this nature, so the reward system was primarily used in maximizing survival and reproductive success.

Now that food is readily available, the neurological system that once helped people recognize the survival advantages of essential eating has now become disadvantageous as it promotes overeating.

Due to human influences, such as global warming and habitat destruction, the environment is changing very rapidly for many organisms, leading to numerous cases of evolutionary mismatch.

Female sea turtles create nests to lay their eggs by digging a pit on the beach, typically between the high tide line and dune, using their rear flippers.

[28] This is because the open horizon of the ocean, illuminated by celestial light, tends to be much brighter in a natural undeveloped beach than the dunes and vegetation.

[29] Numerous cases show that misoriented hatchling sea turtles either die from dehydration, get consumed by a predator, or even burn to death in an abandoned fire.

[32] Before the English Industrial Revolution of the late 18th and early 19th centuries, the most common phenotypic color of the peppered moth was white with black speckles.

When higher air pollution in urban regions killed the lichens adhering to trees and exposed their darker bark,[33] the light-colored moths were easier for predators to see.

Natural selection began favoring a previously rare darker variety of the peppered moth referred to as "carbonaria" because the lighter phenotype had become mismatched to its environment.

Carbonaria frequencies rose above 90% in some areas of England until efforts in the late 1900s to reduce air pollution caused a resurgence of epiphytes, including lichens, to again lighten the color of trees.

The result is an evolutionary mismatch, as a habit that evolved to aid in reproduction has become disadvantageous due to the anthropogenic littering of beer bottles.

[38][39] More specifically, birds often observe the behavior of other organisms to gain valuable information, such as the presence of predators, good breeding sites,[40][41][42] and optimal feeding spots.

To make it less likely to lose a social confrontation, healthy finches are inclined to forage near individuals that are lethargic or listless due to disease.

The relatively short duration of the disease's introduction has caused an inability for the finches to adapt quickly enough to avoid nearing sick individuals, which ultimately results in the mismatch between their behavior and the changing environment.