Sociocultural evolution

More recent approaches focus on changes specific to individual societies and reject the idea that cultures differ primarily according to how far each one has moved along some presumed linear scale of social progress.

Although such theories typically provide models for understanding the relationship between technologies, social structure or the values of a society, they vary as to the extent to which they describe specific mechanisms of variation and change.

While the history of evolutionary thinking with regard to humans can be traced back at least to Aristotle and other Greek philosophers, early sociocultural-evolution theories – the ideas of Auguste Comte (1798–1857), Herbert Spencer (1820–1903) and Lewis Henry Morgan (1818–1881) – developed simultaneously with, but independently of, the work of Charles Darwin (1809-1882) and were popular from late in the 19th century to the end of World War I.

While earlier authors such as Michel de Montaigne (1533–1592) had discussed how societies change through time, the Scottish Enlightenment of the 18th century proved key in the development of the idea of sociocultural evolution.

Although imperial powers settled most differences of opinion with their colonial subjects through force, increased awareness of non-Western peoples raised new questions for European scholars about the nature of society and of culture.

Industrialisation, combined with the intense political change brought about by the French Revolution of 1789 and the U.S. Constitution, which paved the way for the dominance of democracy, forced European thinkers to reconsider some of their assumptions about how society was organised.

[15] Erasmus Darwin therefore flits with abandon through his chronology: Priestman notes that it jumps from the emergence of life onto land, the development of opposable thumbs, and the origin of sexual reproduction directly to modern historical events.

Confronted with these twin issues, Knight's theory ascribes progress to conflict: 'partial discord lends its aid, to tie the complex knots of general harmony'.

The influential German zoologist Ernst Haeckel even wrote that 'natural men are closer to the higher vertebrates than highly civilized Europeans', including not just a racial hierarchy but a civilizational one.

Adam Smith (1723–1790), who held a deeply evolutionary view of human society,[33] identified the growth of freedom as the driving force in a process of stadial societal development.

[36] Both in Darwin's theory of the evolution of species and in Smith's accounts of political economy, competition between selfishly functioning units plays an important and even dominating rôle.

[50] He stressed that humans, driven by emotions, create goals for themselves and strive to realize them (most effectively with the modern scientific method) whereas there is no such intelligence and awareness guiding the non-human world.

[64] This complexity notwithstanding, Boas and Benedict used sophisticated ethnography and more rigorous empirical methods to argue that Spencer, Tylor, and Morgan's theories were speculative and systematically misrepresented ethnographic data.

[65] In sociology, rationalization is the process whereby an increasing number of social actions become based on considerations of teleological efficiency or calculation rather than on motivations derived from morality, emotion, custom, or tradition.

Modern theories are careful to avoid unsourced, ethnocentric speculation, comparisons, or value judgments; more or less regarding individual societies as existing within their own historical contexts.

By the 1940s cultural anthropologists such as Leslie White and Julian Steward sought to revive an evolutionary model on a more scientific basis, and succeeded in establishing an approach known as neoevolutionism.

It bases its theories on empirical evidence from areas of archaeology, palaeontology, and historiography and tries to eliminate any references to systems of values, be it moral or cultural, instead trying to remain objective and simply descriptive.

Leslie White, author of The Evolution of Culture: The Development of Civilization to the Fall of Rome (1959), attempted to create a theory explaining the entire history of humanity.

He questioned the possibility of creating a social theory encompassing the entire evolution of humanity; however, he argued that anthropologists are not limited to describing specific existing cultures.

[70] In his Power and Prestige (1966) and Human Societies: An Introduction to Macrosociology (1974), Gerhard Lenski expands on the works of Leslie White and Lewis Henry Morgan,[70] developing the ecological-evolutionary theory.

[71] He shows those processes on 4 stages of evolution: (I) primitive or foraging, (II) archaic agricultural, (III) classical or "historic" in his terminology, using formalized and universalizing theories about reality and (IV) modern empirical cultures.

For Foucault, the many modern concepts and practices that attempt to uncover "the truth" about human beings (either psychologically, sexually, religion or spiritually) actually create the very types of people they purport to discover.

Sociobiology has remained highly controversial as it contends genes explain specific human behaviours, although sociobiologists describe this role as a very complex and often unpredictable interaction between nature and nurture.

The most notable critics of the view that genes play a direct role in human behaviour have been biologists Richard Lewontin, Steven Rose, and Stephen Jay Gould.

[84] Since the rise of evolutionary psychology, another school of thought, Dual Inheritance Theory, has emerged in the past 25 years that applies the mathematical standards of Population genetics to modeling the adaptive and selective principles of culture.

[87] While they have been developed and popularized in the 1950s and 1960s, their ideological and epistemic ancestors can be traced back until at least the early 20th century when progressivist historians and social scientists, building upon Darwinian ideas that the roots of economic success in the US had to be found in its population structure, which, as an immigrant society, was composed of the strongest and fittest individuals of their respective countries of origin, had started to supply the national myth of US-American manifest destiny with evolutionary reasoning.

The theory of modernization has been subject to some criticism similar to that levied against classical social evolutionism, especially for being too ethnocentric, one-sided and focused on the Western world and its culture.

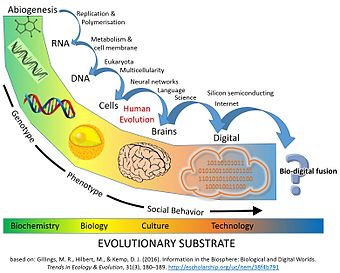

We spend most of our waking time communicating through digitally mediated channels, ...most transactions on the stock market are executed by automated trading algorithms, and our electric grids are in the hands of artificial intelligence.

This approach has been criticised by pointing out that there are a number of historical examples of indigenous peoples doing severe environmental damage (such as the deforestation of Easter Island and the extinction of mammoths in North America) and that proponents of the goal have been trapped by the European stereotype of the noble savage.

An example of this is Ian Morris who argues that given the right geographic conditions, war not only drove much of human culture by integrating societies and increasing material well-being, but paradoxically also made the world much less violent.