Lichen

A lichen (/ˈlaɪkən/ LIE-kən, UK also /ˈlɪtʃən/ LI-chən) is a hybrid colony of algae or cyanobacteria living symbiotically among filaments of multiple fungi species, along with yeasts and bacteria[1][2] embedded in the cortex or "skin", in a mutualistic relationship.

Lichens have since been recognized as important actors in nutrient cycling and producers which many higher trophic feeders feed on, such as reindeer, gastropods, nematodes, mites, and springtails.

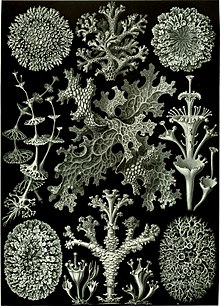

They may have tiny, leafless branches (fruticose); flat leaf-like structures (foliose); grow crust-like, adhering tightly to a surface (substrate) like a thick coat of paint (crustose);[13] have a powder-like appearance (leprose); or other growth forms.

[16][18] They are abundant growing on bark, leaves, mosses, or other lichens[15] and hanging from branches "living on thin air" (epiphytes) in rainforests and in temperate woodland.

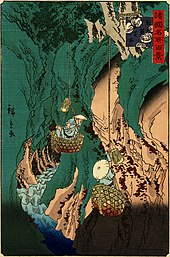

Various lichens have adapted to survive in some of the most extreme environments on Earth: arctic tundra, hot dry deserts, rocky coasts, and toxic slag heaps.

[15][20] They can be seen as being relatively self-contained miniature ecosystems, where the fungi, algae, or cyanobacteria have the potential to engage with other microorganisms in a functioning system that may evolve as an even more complex composite organism.

When a crustose lichen gets old, the center may start to crack up like old-dried paint, old-broken asphalt paving, or like the polygonal "islands" of cracked-up mud in a dried lakebed.

[41] Colonies of lichens may be spectacular in appearance, dominating much of the surface of the visual landscape in forests and natural places, such as the vertical "paint" covering the vast rock faces of Yosemite National Park.

[citation needed] In lichens that include both green algal and cyanobacterial symbionts, the cyanobacteria may be held on the upper or lower surface in small pustules called cephalodia.

[45] Algae produce sugars that are absorbed by the fungus by diffusion into special fungal hyphae called appressoria or haustoria in contact with the wall of the algal cells.

A few lichen species can tolerate fairly high levels of pollution, and are commonly found in urban areas, on pavements, walls and tree bark.

Since industrialisation, many of the shrubby and leafy lichens such as Ramalina, Usnea and Lobaria species have very limited ranges, often being confined to the areas which have the cleanest air.

In an experiment led by Leopoldo Sancho from the Complutense University of Madrid, two species of lichen—Rhizocarpon geographicum and Rusavskia elegans—were sealed in a capsule and launched on a Russian Soyuz rocket 31 May 2005.

Some lichen fungi belong to the phylum Basidiomycota (basidiolichens) and produce mushroom-like reproductive structures resembling those of their nonlichenized relatives.

[15]: 14 A "podetium" (plural: podetia) is a lichenized stalk-like structure of the fruiting body rising from the thallus, associated with some fungi that produce a fungal apothecium.

Living as a symbiont in a lichen appears to be a successful way for a fungus to derive essential nutrients, since about 20% of all fungal species have acquired this mode of life.

[45] Approximately 100 species of photosynthetic partners from 40[45] genera and five distinct classes (prokaryotic: Cyanophyceae; eukaryotic: Trebouxiophyceae, Phaeophyceae, Chlorophyceae) have been found to associate with the lichen-forming fungi.

[37] If putting a drop on a lichen turns an area bright yellow to orange, this helps identify it as belonging to either the genus Cladonia or Lecanora.

[107] Lichen fragments are also found in fossil leaf beds, such as Lobaria from Trinity County in northern California, US, dating back to the early to middle Miocene.

[131] Lecanoromycetes, one of the most common classes of lichen-forming fungi, diverged from its ancestor, which may have also been lichen forming, around 258 million years ago, during the late Paleozoic period.

They can survive in some of the most extreme environments on Earth: arctic tundra, hot dry deserts, rocky coasts, and toxic slag heaps.

For example, there is an ongoing lichen growth problem on Mount Rushmore National Memorial that requires the employment of mountain-climbing conservators to clean the monument.

[140] A major ecophysiological advantage of lichens is that they are poikilohydric (poikilo- variable, hydric- relating to water), meaning that though they have little control over the status of their hydration, they can tolerate irregular and extended periods of severe desiccation.

Also lacking stomata and a cuticle, lichens may absorb aerosols and gases over the entire thallus surface from which they may readily diffuse to the photobiont layer.

[citation needed] In the past, Iceland moss (Cetraria islandica) was an important source of food for humans in northern Europe, and was cooked as a bread, porridge, pudding, soup, or salad.

[153][154][155] Many lichens produce secondary compounds, including pigments that reduce harmful amounts of sunlight and powerful toxins that deter herbivores or kill bacteria.

Historically, in traditional medicine of Europe, Lobaria pulmonaria was collected in large quantities as "lungwort", due to its lung-like appearance (the "doctrine of signatures" suggesting that herbs can treat body parts that they physically resemble).Similarly, Peltigera leucophlebia ("ruffled freckled pelt") was used as a supposed cure for thrush, due to the resemblance of its cephalodia to the appearance of the disease.

[162] The 10th century Arab physician Al-Tamimi mentions lichens dissolved in vinegar and rose water being used in his day for the treatment of skin diseases and rashes.

[164] Schwendener's hypothesis, which at the time lacked experimental evidence, arose from his extensive analysis of the anatomy and development in lichens, algae, and fungi using a light microscope.

[164] Other prominent biologists, such as Heinrich Anton de Bary, Albert Bernhard Frank, Beatrix Potter, Melchior Treub and Hermann Hellriegel, were not so quick to reject Schwendener's ideas and the concept soon spread into other areas of study, such as microbial, plant, animal and human pathogens.

(a) The cortex is the outer layer of tightly woven fungus filaments ( hyphae )

(b) This photobiont layer has photosynthesizing green algae

(c) Loosely packed hyphae in the medulla

(d) A tightly woven lower cortex

(e) Anchoring hyphae called rhizines where the fungus attaches to the substrate