Experience curve effects

The effect has large implications for costs[3] and market share, which can increase competitive advantage over time.

[4] An early empirical demonstration of learning curves was produced in 1885 by the German psychologist Hermann Ebbinghaus.

[5][6] He found that performance increased in proportion to experience (practice and testing) on memorizing the word set.

This relationship was probably first quantified in the industrial setting in 1936 by Theodore Paul Wright, an engineer at Curtiss-Wright in the United States.

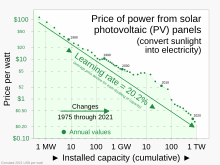

The learning curve model posits that for each doubling of the total quantity of items produced, costs decrease by a fixed proportion.

Each time cumulative volume doubles, value-added costs (including administration, marketing, distribution, and manufacturing) fall by a constant percentage.

The phrase experience curve was proposed by Bruce D. Henderson, the founder of the Boston Consulting Group (BCG), based on analyses of overall cost behavior in the 1960s.

The equations for these effects come from the usefulness of mathematical models for certain somewhat predictable aspects of those generally non-deterministic processes.

[4][13] According to Henderson, BCG's first "attempt to explain cost behavior over time in a process industry" began in 1966.

"[4]The suggestion was that failure of production to show the learning curve effect was a risk indicator.

One consequence of experience curve strategy is that it predicts that cost savings should be passed on as price decreases rather than kept as profit margin increases.

High profits would encourage competitors to enter the market, triggering a steep price decline and a competitive shakeout.