Expressionist music

Adorno also describes it as concerned with the unconscious, and states that "the depiction of fear lies at the centre" of expressionist music, with dissonance predominating, so that the "harmonious, affirmative element of art is banished".

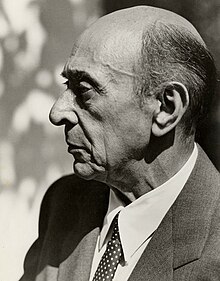

[4] The three central figures of musical expressionism are Arnold Schoenberg (1874–1951) and his pupils, Anton Webern (1883–1945) and Alban Berg (1885–1935), the so-called Second Viennese School.

23b, 1922, setting six poems of Georg Trakl), Igor Stravinsky (1882–1971) (Three Japanese Lyrics, 1913), Alexander Scriabin (1872–1915) (late piano sonatas).

[5] Another significant expressionist was Béla Bartók (1881–1945) in early works, written in the second decade of the 20th century, such as Bluebeard's Castle (1911),[6] The Wooden Prince (1917),[7] and The Miraculous Mandarin (1919).

[8] American composers with a sympathetic "urge for such intensification of expression" who were active in the same period as Schoenberg's expressionist free atonal compositions (between 1908 and 1921) include Carl Ruggles, Dane Rudhyar, and, "to a certain extent", Charles Ives, whose song "Walt Whitman" is a particularly clear example.

[10]Mitchell 2005, 334 Later composers, such as Peter Maxwell Davies (1934–2016), "have sometimes been seen as perpetuating the Expressionism of Schoenberg, Berg, and Webern",[11] and Heinz Holliger's (b.

1939) most distinctive trait "is an intensely engaged evocation of ... the essentially lyric expressionism found in Schoenberg, Berg and, especially, Webern".

[citation needed] The author of the libretto, Marie Pappenheim, was a recently graduated medical student familiar with Freud's newly developed theories of psychoanalysis, as was Schoenberg himself.

These were constructed freely, based upon the subconscious will, unmediated by the conscious, anticipating the main shared ideal of the composer's relationship with the painter Wassily Kandinsky.

In around 1911, the painter Wassily Kandinsky wrote a letter to Schoenberg, which initiated a long lasting friendship and working relationship.

This heightens the immediacy and intelligibility of the plot, but is somewhat contradictory with the ideals of Schoenberg's expressionism, which seeks to express musically the subconscious unmediated by the conscious.

According to one view, "Musically complex and highly expressionistic in idiom, Lulu was composed entirely in the 12-tone system",[17] but this is by no means a universally accepted interpretation.

[19] In contrast to the plainly expressionist manner of Wozzeck, therefore, Lulu is closer to the Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity) of the 1920s, and to Bertolt Brecht's epic theatre.

As can be seen, Arnold Schoenberg was a central figure in musical expressionism, although Berg, Webern, and Bartók did also contribute significantly, along with various other composers.