Expulsion of congregations

This strengthening of the regime was marked by militant anticlericalism from moderate Republicans and Radicals [fr] and by a desire to remove education from the influence of congregations, which were mocked as a "Roman militia" and accused of being seeds of counter-revolution.

Some opted to persist in living in small community groups in houses provided by laypeople, while others chose to exile themselves to reconstitute their congregations abroad, with Spain being the principal destination for Congregationalists.

[5] The flagship of their educational enterprise, the Collège de la Montagne Sainte-Geneviève, located on Rue des Postes [fr], prepared its students for the entrance examinations to the École Polytechnique and Saint-Cyr.

[4] This anticlericalism was further fueled by French Freemasonry, which sought to eradicate the regular clergy, viewing their vow of obedience as enslaving their lives to an obscurantist authority, in contradiction to Article 1780 of the Civil Code, which states that "no one can bind their services except for a limited time.

Their religious teachings were also subjected to criticism, with casuistry being accused of promoting immorality; this was particularly evident in the pamphlet La Morale des Jésuites by Republican Paul Bert, who later became the founder of secular education.

[11] From 1877, the year in which the Center-Left assumed power and permanently displaced the monarchists, a purge of the civil service commenced, intending to remove officials affiliated with the Moral Order [fr].

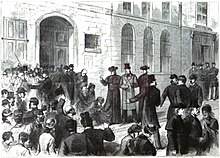

[12] From 1878 to 1880, a series of violent attacks on religious congregations accompanied a press campaign targeting the clergy in the context of the secularization of communal schools by the Paris Municipal Council, which had been authorized by a circular issued in 1878.

[18] On June 10, 1880, the Minister of Justice summoned the attorneys general to the ministry and provided them with verbal instructions, emphasizing the necessity of strict adherence to the established standards to avoid dismissal.

However, clandestine discussions resumed, and the resulting accord entailed the following stipulations: in exchange for the congregations' formal attestation of their fidelity and acquiescence to the Republican order, the government would refrain from enforcing the second decree.

Colonel Riu rushes through the benches, descends into the hemicycle, checking to see if his men are following him, imitating his valiant ardor, then he ascends towards Mr. Baudry d'Asson, adopts a courteous demeanor, and orders his soldiers to form a circle around the honorable deputy and his friends.

[36] Speaking on behalf of Catholics, he denounced the arbitrary nature of the government's measures and proposed a vote on a law to regularize the existence of unauthorized congregations by recognizing the right of association.

[41] This internal dissension can be explained by Pope Leo XIII's conciliatory approach, which sought a resolution through negotiation and only raised protests in a measured manner once a breach had occurred.

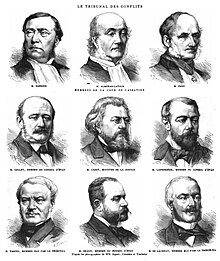

[51] Many court presidents voiced opposition to the enforcement of the March 1880 decrees by extending a favorable reception to the requests of expelled religious individuals and issuing orders for their expeditious reinstatement to their properties.

[48] The courts of Aix-en-Provence, Angers, Avignon, Béthune, Bordeaux, Bourges, Clermont, Douai, Grenoble, La Flèche, Le Puy-en-Velay, Lille, Limoges, Lyon, Marseille, Nancy, Nantes, Paris, Périgueux, Quimper, Rouen, and Toulouse deemed themselves to possess the requisite competence.

This ruling was based on a legally acceptable foundation;the 1880 decrees specified the application of the decree-law of 3 Messidor, Year XII (June 22, 1804), which stipulated that "our attorneys general and our imperial prosecutors are obliged to [...] "Prosecute and have prosecuted, even by extraordinary means, as the cases require, persons of any sex who would directly or indirectly violate this decree," thus placing the prohibition of congregations under the sanction of judicial authority and not explicitly excluding the intervention of the judicial judge to guarantee the fundamental rights of the individual.

President Leroux de Bretagne, portraying himself as a champion of individual liberties, declared the decrees invalid and issued a reinstatement order in early July 1880, thereby annulling the expulsion of the Christian Brothers congregation.

Conflicts raised everywhere claim for the government alone the absolute, indefinite, sovereign, uncontrollable right to dispose of the property, freedom, and homes of citizens, as necessary for the dispersal of unauthorized congregations!

And today, while even at the very hour I speak, the public force may still be continuing its sad task, while the government sits in person within this tribunal, you are asked, not to give judges, but to suppress them!

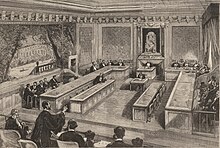

The latter presided over the Tribunal as Minister of Justice, yet Me Bosviel questioned his impartiality due to Cazot's role as one of the authors of the March 1880 decrees and his repeated declaration of himself as "the worst enemy" of the congregations.

[57] Following a period of deliberation, the court concluded that "the Tribunal des Conflits, established to ensure the application of the principle of the separation of administrative and judicial powers, is not called upon to rule on any private interest dispute."

The Tribunal's rationale for this decision is as follows:[58] Considering that it cannot be the role of the judiciary to annul the effects and prevent the execution of this administrative act; that, certainly, as a formal exception to the principle of the separation of powers, this authority can assess the legality of police actions when it is called upon to impose a penalty against offenders, but that this exception does not apply to the present case; — Considering that if Mr. Marquigny and others believed they were justified in arguing that the measure taken against them was not authorized by any law and that, consequently, the decree of March 29, 1880, and the aforementioned order were tainted with excess of power, it was to the administrative authority that they should have turned to seek the annulment of these acts; — Considering that the president of the Lille Tribunal, in declaring himself competent, misunderstood the principle of the separation of powers, [...]Subsequently, the Tribunal rendered a similar decision in favor of the Prefect of Vaucluse [fr].

[62] On November 8, 1880, in Limoges, the Tribunal des Conflits was deemed powerless to act in the face of the "rigorous duty of a magistrate to hear the complaints of citizens violently thrown out of their homes."

In his investigation, Judge Rogues de Fursac invoked the decree of September 8, 1870, to challenge the immunity [fr] of high-ranking officials and justify the lawsuit filed by the Oblates of Mary Immaculate and the Franciscans.

[43] The Minister of Public Instruction, Jules Ferry, who was opposed to the continued existence of these institutions, ordered their closure through academic councils [fr] under the pretext of "reconstitution de congrégation."

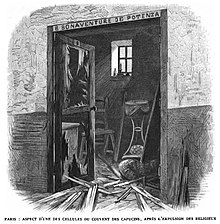

A second door was then forced open to gain access to the cloister, where Father Provincial Arsène, the other religious, and thirty laypeople, including Libman, Ozanam, Ponton d'Amécourt, and de Fourcy, were located.

The police, with the assistance of the gendarmerie, were unable to execute the decrees due to the fact that approximately sixty religious figures had barricaded themselves within the abbey with three thousand laypeople,[76] including Frédéric Mistral,[38] Joseph de Cadillan [fr] (former deputy and mayor of Tarascon), Hyacinthe Chauffard (former master of requests and publicist Count Hélion de Barrème, and Count Pierre Terray [fr] (future mayor of Barbentane).

The Marquis of Molins, the Spanish ambassador, observed that the actions of the opportunist republicans "enact[ed] the most severe measures against clergy, while a broad amnesty is proclaimed towards the murderers and arsonists of the Commune."

[95] For Jules Ferry and the Republican Left [fr], the expulsion of the congregations represented merely a preliminary step in their broader campaign against clericalism and in favor of secularizing education.

Consequently, on December 21, 1880, shortly after the implementation of the decrees, Deputy Camille Sée, a close associate of Jules Ferry, proposed a legislative measure to establish public secondary education for girls [fr], wherein catechism would be replaced by courses in secular morality.

Subsequently, Jules Ferry facilitated the establishment of the École Normale Supérieure de Sèvres, which was designed to train female teachers for the newly created girls' lycées.