Marianne

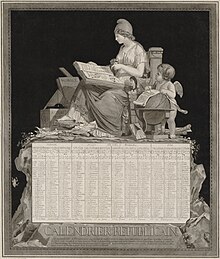

[2] In September 1792, the National Convention decided by decree that the new seal of the state would represent a standing woman holding a spear with a Phrygian cap held aloft on top of it.

Historian Maurice Agulhon, who in several works set out on a detailed investigation to discover the origins of Marianne, suggests that it is the traditions and mentality of the French that led to the use of a woman to represent the Republic.

Although the image of Marianne did not garner significant attention until 1792, the origins of this "goddess of Liberty" date back to 1775, when Jean-Michel Moreau painted her as a young woman dressed in Roman style clothing with a Phrygian cap atop a pike held in one hand[5] that years later would become a national symbol across France.

Although she is standing and holding a pike, this depiction of Marianne is "not exactly aggressive",[7] representing the ideology of the moderate-liberal Girondins in the National Convention as they tried to move away from the "frantic violence of the revolutionary days".

By 1793, the conservative figure of Marianne had been replaced by a more violent image; that of a woman, bare-breasted and fierce of visage, often leading men into battle.

In the Official Vignette of the Executive Directory, 1798, Marianne made a return, still depicted wearing the Phrygian cap, but now surrounded by different symbols.

The symbol of Marianne continued to evolve in response to the needs of the State long after the Directory was dissolved in 1799 following the coup spearheaded by Emmanuel-Joseph Sieyès and Napoleon Bonaparte.

One is fighting and victorious, recalling the Greek goddess Athena: she has a bare breast, the Phrygian cap and a red corsage, and has an arm lifted in a gesture of rebellion.

"[11] Hobsbawm argued for this reason, that unlike Marianne who was a symbol of the republic and freedom in general, her German counterpart, Deutscher Michel "...seems to have been essentially an anti-foreign image".

Aimé-Jules Dalou lost the contest against the Morice brothers, but the City of Paris decided to build his monument on the Place de la Nation, inaugurated for the centenary of the French Revolution, in 1889, with a plaster version covered in bronze.

Dalou's Marianne had the lictor's fasces, the Phrygian cap, a bare breast, and was accompanied by a Blacksmith representing Work, and allegories of Freedom, Justice, Education and Peace: all that the Republic was supposed to bring to its citizens.

[13] In Imperial Germany, Marianne was usually portrayed in a manner that was very vulgar, usually suggesting that she was a prostitute or at any rate widely promiscuous while at the same time being a hysterically jealous and insane woman who however always cowered in fear at the sight of a German soldier.

[14] The German state in the Imperial period promoted a very xenophobic militarism, which portrayed the Reich as forever in danger from foreigners and in need of an authoritarian government.

[14] The American historian Michael Nolan wrote in the "hyper-masculine world of Wilhelmine Germany" with its exaltation of militarism and masculine power, the very fact that Marianne was the symbol of the republic was used to argue that French men were effeminate and weak.

[12] For those on the French right, who still hankered for the House of Bourbon like Action Française, Marianne was always rejected for her republican associations, and the preferred symbol of France was Joan of Arc.

[16] As Joan of Arc was devoutly Catholic, committed to serving King Charles VII, and fought for France against England, she perfectly symbolized the values of Catholicism, royalism, militarism and nationalism that were so dear for French monarchists.

[17] Joan was apparently asexual, and her chaste and virginal image stood in marked contrast to Marianne, whom Action Française depicted as a prostitute or as a "slut" to symbolize the "degeneracy" of the republic.

[20] In the middle of the 19th century, Marianne was usually portrayed in France as a young woman, but by late 19th century, Marianne was more commonly presented as a middle aged, maternal woman, reflecting the fact that the republic was dominated by a centre-right coalition of older male politicians, who disliked the image of a militant young female revolutionary.

During World War II, Marianne represented Liberty against the Nazi invaders, and the Republic against the Vichy regime (see Paul Collin's representation).

[27] Marianne's presence became less important in French imagery after World War II, although under the presidency of Charles de Gaulle she was often used, in particular on stamps or for referendums.

The liberal and conservative president Valéry Giscard d'Estaing replaced Marianne by La Poste on stamps, changed the rhythm of the Marseillaise and suppressed the commemoration of 8 May 1945.

The Socialist President François Mitterrand aimed to make the celebrations a consensual event, gathering all citizens, recalling more the Republic than the Revolution.

The American opera singer Jessye Norman took Marianne's place, singing La Marseillaise as part of an elaborate pageant orchestrated by avant-garde designer Jean-Paul Goude.

A recent discovery establishes that the first written mention of the name of Marianne to designate the Republic appeared in October 1792 in Puylaurens in the Tarn département near Toulouse.

"[citation needed] The description by artist Honoré Daumier in 1848, as a mother nursing two children, Romulus and Remus, or by sculptor François Rude, during the July Monarchy, as a warrior voicing the Marseillaise on the Arc de Triomphe, are uncertain.

[4] She was followed by Michèle Morgan (1972), Mireille Mathieu (1978), Catherine Deneuve (1985), Inès de La Fressange (1989), Laetitia Casta (2000) and Évelyne Thomas (2003).

[31] In July 2013, a new stamp featuring the Marianne was debuted by President François Hollande, allegedly designed by the team of Olivier Ciappa and David Kawena.

Ciappa claimed that Inna Shevchenko, a high-profile member of the Ukrainian protest group FEMEN who had recently been granted political asylum in France, was a main inspiration for the new Marianne.

[41] Angelique Chisafis of The Guardian newspaper reported: "The inference that bare breasts were a symbol of France while the Muslim headscarf was problematic sparked scorn from politicians and derision from historians and feminists".

[41] The French president François Hollande sparked much debate in France with his controversial statement "The veiled woman will be the Marianne of tomorrow".