Externality

Marshall's formulation of externalities laid the groundwork for subsequent scholarly inquiry into the broader societal impacts of economic actions.

While Marshall provided the initial conceptual framework for externalities, it was Arthur Pigou, a British economist, who further developed the concept in his influential work, "The Economics of Welfare," published in 1920.

Knight's work highlighted the inherent challenges in quantifying and mitigating externalities within market systems, underscoring the complexities involved in achieving optimal resource allocation.

Scholars such as Ronald Coase and Harold Hotelling made significant contributions to the understanding of externalities and their implications for market efficiency and welfare.

The recognition of externalities as a pervasive phenomenon with wide-ranging implications has led to its incorporation into various fields beyond economics, including environmental science, public health, and urban planning.

Contemporary debates surrounding issues such as climate change, pollution, and resource depletion underscore the enduring relevance of the concept of externalities in addressing pressing societal challenges.

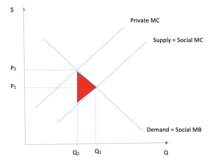

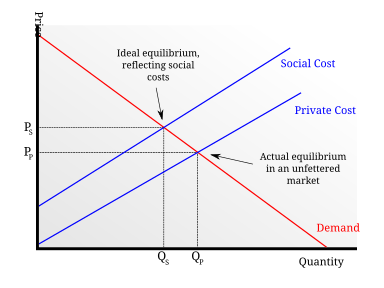

The consequences of producer or consumer behaviors that result in external costs or advantages imposed on others are not taken into account by market pricing and can have both positive and negative effects.

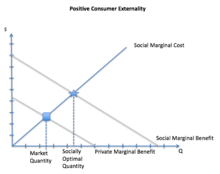

On the other hand, positive externalities occur when the activities of producers or consumers benefit other parties in ways that are not accounted for in market exchanges.

Through the integration of externalities into economic research and policy formulation, society may endeavor to get results that optimize aggregate well-being and foster sustainable growth.

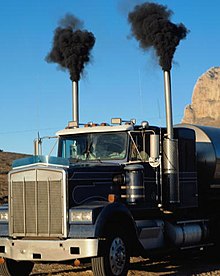

The person who is affected by the negative externalities in the case of air pollution will see it as lowered utility: either subjective displeasure or potentially explicit costs, such as higher medical expenses.

The market-driven approach to correcting externalities is to internalize third party costs and benefits, for example, by requiring a polluter to repair any damage caused.

This hypothesis challenges the conventional microeconomic model, as outlined by the Common Pool Resource (CPR) mechanism, which typically assumes that an individual's utility derived from consuming a particular good or service remains unaffected by other's consumption choices.

Prices rise in response to shifts in consumer preferences or income levels, which raise demand for a product and benefit suppliers by increasing sales and profits.

As a result, consumers who were not involved in the initial transaction suffer a monetary externality in the form of diminished buying power, while producers profit from increased prices.

Consequently, early adopters could gain financially from positive pecuniary externalities such as enhanced network effects or greater resale prices of related products or services.

In addition, workers in some industries may experience job displacement and unemployment as a result of disruptive developments in labor markets brought about by technological improvements.

For instance, individuals with outdated skills may lose their jobs as a result of the automation of manufacturing processes through robots and artificial intelligence, causing social and economic unrest in the affected areas.

The result in an unfettered market is inefficient since at the quantity Qp, the social benefit is greater than the societal cost, so society as a whole would be better off if more goods had been produced.

While property rights to some things, such as objects, land, and money can be easily defined and protected, air, water, and wild animals often flow freely across personal and political borders, making it much more difficult to assign ownership.

Due to their rivalrous usage and non-excludability, common pool resources including fisheries, forests, and grazing areas are vulnerable to abuse and deterioration when access is unrestrained.

Without clearly defined property rights or efficient management structures, people or organizations may misuse common pool resources without thinking through the long-term effects, which might have detrimental externalities on other users and society at large.

In order to maintain their way of life and earn income, fishers are motivated to maximize their catches, which eventually causes overfishing and the depletion of fish populations.

He does, however, contend that private parties can establish mutually advantageous arrangements to internalize externalities without the involvement of the government, provided that there are minimal transaction costs and clearly defined property rights.

In a society where property rights are well-defined and transaction costs are minimal, the farmer and rancher can work out a voluntary agreement to settle the dispute.

In a dynamic setup, Rosenkranz and Schmitz (2007) have shown that the impossibility to rule out Coasean bargaining tomorrow may actually justify Pigouvian intervention today.

Knight argues that, if a large number of vehicles operate between the two destinations and have freedom to choose between the routes, they will distribute themselves in proportions such that the cost per unit of transportation will be the same for every truck on both highways.

The negative effect of carbon emissions and other greenhouse gases produced in production exacerbate the numerous environmental and human impacts of anthropogenic climate change.

The tax incentivised producers to either lower their production levels or to undertake abatement activities that reduce emissions by switching to cleaner technology or inputs.

[77] These arguments are developed further by Hawken, Amory and Hunter Lovins to promote their vision of an environmental capitalist utopia in Natural Capitalism: Creating the Next Industrial Revolution.

[79] Rather than assuming some (new) form of capitalism is the best way forward, an older ecological economic critique questions the very idea of internalizing externalities as providing some corrective to the current system.