Geography of Paraguay

About 95 percent of Paraguay's population resides in the Paraneña region, which has all the significant orographic features and a more predictable climate.

The plateau slopes moderately to east and south, its remarkably uniform surface interrupted only by the narrow valleys carved by the westward-flowing tributaries of the Río Paraná.

Between these two upland subregions lies the Central Lowland, an area of low elevation and relief, sloping gently upward from the Río Paraguay toward the Paraná Plateau.

The valleys of the Central Lowland's westward-flowing rivers are broad and shallow, and periodic flooding of their courses creates seasonal swamps.

Apparently the weathered remnants of rock related to geological formations farther to the east, these hills are called islas de monte (mountain islands), and their margins are known as costas (coasts).

The Cordillera de Amambay extends from the northeast corner of the region south and slightly east along the Brazilian border.

The main chain, 200 kilometers (120 mi) long, has smaller branches that extend to the west and die out along the banks of the Río Paraguay in the Northern Upland.

The Río Paraná forms the Salto del Guairá waterfall where it cuts through the mountains of the Cordillera de Mbaracayú to enter Argentina.

The Cordillera de Caaguazú falls where the other two main mountain ranges meet and extends south, with an average height of 400 meters (1,300 ft).

The Serranía de Mbaracayú extends east and then south to parallel the Río Paraná; the mountain chain has an average height of 500 meters (1,600 ft).

One prominent wetland of the Bajo Chaco is the Estero Patiño, which at 1,500 km2 (580 sq mi) forms the largest swamp in the country.

A belt about 50 km (30 mi) in length along the Paraguay River again has a different evergreen vegetation of wetlands and palm tree forests (Bajo Chaco).

The lowlands facing the Paraguay River have insufficient drainage and seasonal flooding (which again increases soil fertility) as a constraint.

The word Paraguay can be translated as the Paradise of Waters, as there is plenty to be found all around the country, including underneath it; see Guarani Aquifer.

Medium-sized ocean vessels can sometimes reach Asunción, but the twisting meanders and shifting sandbars can make this transit difficult.

The major tributaries entering the Paraguay River from the Paraneña region—such as the Apa, Aquidabán, and Tebicuary Rivers—descend rapidly from their sources in the Paraná Plateau to the lower lands.

In general, the Río Paraná is navigable by large ships only up to Encarnación in Southern Paraguay but smaller boats may go somewhat further north.

In many parts of the region, the water table is only a meter beneath the surface of the ground, and there are numerous small ponds and seasonal marshes.

Because of the seasonal overflow of the numerous westward-flowing streams, the lowland areas of the Paraneña region also experience poor drainage conditions, particularly in the Ñeembucú Plain in the southwest, where an almost impervious clay subsurface prevents the absorption of excess surface water into the aquifer.

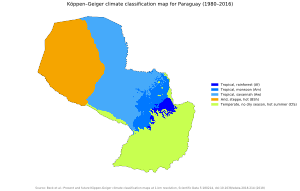

During the Southern Hemisphere's summer, which corresponds to the northern winter, the dominant influence on the climate is the warm sirocco winds blowing out of the northeast.

During the winter, the dominant wind is the cold pampero from the South Atlantic, which blows across Argentina and is deflected northeastward by the Andes in the southern part of that country.

Because of the lack of topographic barriers within Paraguay, these opposite prevailing winds bring about abrupt and irregular changes in the usually moderate weather.

The number of days with temperatures falling below freezing ranges from as few as three to as many as sixteen yearly, and with even wider variations deep in the interior.

No part of the Paraneña region is entirely free from the possibility of frost and consequent damage to crops, and snow flurries have been reported in various locations.

As the soggy heat nears intolerable limits, thunderstorms preceding a cold front will blow in from the south, and temperatures will drop as much as 15 °C (25 °F) in a few minutes.

Although local meteorological conditions play a contributing role, rain usually falls when tropical air masses are dominant.

Current environmental issues include deforestation (Paraguay lost an estimated 20,000 km2 of forest land between 1958 and 1985) and water pollution (inadequate means for waste disposal present health risks for many urban residents).