Fall of Outremer

Traditionally, the end of Western European presence in the Holy Land is identified as their defeat at the Siege of Acre in 1291, but the Christian forces managed to hold on to the small island fortress of Ruad until 1302.

At the Second Council of Lyon in 1274, Gregory X, who had accompanied Edward I of England to the Holy Land, preached a new crusade to an assembly which included envoys from both the Byzantine emperor Michael VIII Paliollogos and the Mongol Ilkhan Abaqa, as well as from the princes of the West.

Gregory was successful in temporarily uniting the churches of Rome and Constantinople, and in securing Byzantine support for his new crusade, which reflected a general alarm at the plans of Charles I of Anjou.

The Mamluks conveyed a forged letter from Grand Master Hugues de Revel directing the surrender of the garrison and on 8 April they capitulated and were allowed to travel to Tripoli.

Barthélémy de Maraclée, a vassal of Bohemond, fled the attack and took refuge in Persia at the court of Abaqa, where he pleaded with the Mongol Ilkhan to intervene in the Holy Land.

Notable examples included the following:[14] The Second Council of Lyon convened the next year to consider three major themes: (1) union with the Greeks, (2) the crusade, and (3) the reform of the church.

[24] In 1273, Gregory had prepared for the union of the churches by sending an embassy to Constantinople, and by inducing Charles I of Anjou and Philip I of Courtenay, Latin Emperor in exile, to moderate their political ambitions.

On 6 July, after a sermon by Pierre de Tarentaise and the public reading of the letter from the emperor, the Byzantines pledged fidelity to Rome and promised protection of Christians in the Holy Land.

[26] The council followed Gregory's lead and drew up plans for a crusade to recover the Holy Land, to be financed by a tithe imposed for six years on all the benefices of Christendom.

This text put forward four main milestones to accomplish the Crusade: (1) the imposition of a new tax over three years; (2) the interdiction of any kind of trade with the Muslims; (3) the supply of ships by the Italian maritime republics; and (4) the alliance of the West with Byzantium and the Ilkhanate.

During John's eight-month papacy, he attempted to launch a crusade for the recovery of the Holy Land, pushed for a union with the Eastern church, and did what he could to maintain peace between the Christian nations.

[36] Honorius inherited plans for another crusade, but confined himself to collecting the tithes imposed at Lyon, arranging with the great banking houses of Italy to act as his agents.

A new crusade to the Holy Land remained his principal goal and persuaded Charles to start negotiations with Maria of Antioch about purchasing her claim to the Kingdom of Jerusalem.

Nicholas III died on 22 August 1280 and, after much intrigue, one of Charles' staunchest supporter was elected as pope Martin IV on 22 February 1281, dismissing his predecessor's relatives.

They were willing to unite their troops to prevent Charles' army from taking possession of the kingdom, but Philip III of France strongly opposed his mother's plan and Edward I would not promise any assistance to them.

In 1279, a former chancellor of Manfred of Sicily named John of Procida is credited with plotting against Charles convincing Michael VIII Palaeologus, the Sicilian barons and Nicholas III to support a revolt.

Through John's secret diplomatic actions the conditions were set enabling the destruction of Charles' crusading invasion fleet (aimed first at recapturing Constantinople) at anchor in Messina.

With a succession of new popes that year, the Papal Curia was very influential and strongly influenced by Charles I of Anjou, who disliked the Mongols intensely as the friends of his enemies, the Byzantines and the Genoese.

As his predecessor had, Qalawun entered into land control treaties with what was left of the Crusader states, Military Orders and individual lords who wished to remain independent.

[71] Qalawun's early reign was marked by policies that were meant to gain the support of important societal elements, namely the merchant class, the Muslim bureaucracy and the religious establishment.

In contrast to his Mamluk predecessors who focused on establishing madrasas, the complex was built to gain the goodwill of the public, create a lasting legacy, and secure his spot in the afterlife.

The Aragonese seized Reggio Calabria in February and the Sicilian admiral, Roger of Lauria, annihilated a newly raised Provençal fleet at Malta in April.

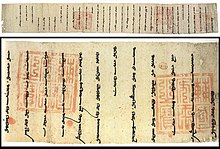

The letter was delivered by a Christian on the khan's court, Isa Kelemechi, who offered to remove the Mamluks and divide Egypt (called the land of Sham) with the Franks.

He and Gobert de Helleville left Rome in the late spring of 1288, laden with precious relics including a tiara to be presented to Yahballaha and with letters to the Ilkhan court and the Jacobite bishop of Tabriz.

In 1289, Nicholas dispatched the Franciscan Giovanni da Montecorvino[97] as papal legate to Kubilai Khan, Arghun, and other leading personages of the Mongol Empire, as well as to Yagbe'u Seyon, emperor of Ethiopia.

[104] The city and port, as the last remnant of the Principality of Antioch, was not covered by the truce with Tripoli, and so Qalawun sent the Aleppine emir Husam ad-Din Turantai, to take the town.

James II of Aragon pledged to provide a force of almogavares and crossbowmen over the next two years, despite having promised Qalawun not to join a crusade in exchange for trading privileges.

Reflecting on this event, Kurdish historian Abu'l Fida wrote: These conquests [meant that] the whole of Palestine was now in Muslim hands, a result that no one would have dared to hope for or to desire.

This story of wishful thinking was so popular in France that in 1846, a large-scale painting was created by Claude Jacquand titled Molay Prend Jerusalem, 1299 , which depicts the supposed event.

[142] The principal work that chronicling the fall of Outremer is Les Gestes des Chiprois (Deeds of the Cypriots),[143] by an unknown historian referred to as Templar of Tyre.