Fall of Saigon

The aftermath ushered in a transition period under North Vietnamese control, culminating in the formal reunification of the country as the Socialist Republic of Vietnam under communist rule on 2 July 1976.

Even as that memo was being released, Dũng was preparing a major offensive in the Central Highlands of Vietnam, which began on 10 March and led to the capture of Buôn Ma Thuột.

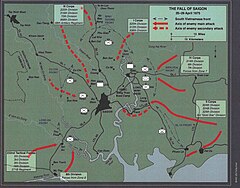

[27] Supported by artillery and armor, the PAVN continued to march towards Saigon, capturing the major cities of northern South Vietnam at the end of March—Huế on the 25th and Đà Nẵng on the 28th.

After the loss of Đà Nẵng, those prospects had already been dismissed as nonexistent by CIA officers in Vietnam, who believed that nothing short of B-52 strikes against Hanoi could possibly stop the North Vietnamese.

[29] By 8 April, the North Vietnamese Politburo, which in March had recommended caution to Dũng, cabled him to demand "unremitting vigor in the attack all the way to the heart of Saigon.

[31] Meanwhile, South Vietnam failed to garner any significant increase in military aid from the United States, snuffing out President Nguyễn Văn Thiệu's hopes for renewed American support.

On 9 April, PAVN forces reached Xuân Lộc, the last line of defense before Saigon, where the ARVN 18th Division made a last stand and held the city through fierce fighting for 11 days.

[citation needed] The rapid PAVN advances of March and early April led to increased concern in Saigon that the city, which had been fairly peaceful throughout the war and whose people had endured relatively little suffering, was soon to come under direct attack.

[36] More recently, eight Americans captured in Buôn Ma Thuột had vanished and reports of beheadings and other executions were filtering through from Huế and Đà Nẵng, mostly spurred on by government propaganda.

His desire for this was to prevent total chaos and to deflect the real possibility of South Vietnamese turning against Americans and to keep all-out bloodshed from occurring.

[citation needed] Ford approved a plan between the extremes in which all but 1,250 Americans—few enough to be removed in a single day's helicopter airlift—would be evacuated quickly; the remaining 1,250 would only leave when the airport was threatened.

National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger was opposed to a full-scale evacuation as long as the aid option remained on the table because the removal of American forces would signal a loss of faith in Thiệu and severely weaken him.

Eventually, White House lawyers determined that the use of American forces to rescue citizens in an emergency was unlikely to run afoul of the law, but the legality of using military assets to withdraw refugees was unknown.

[45] Those who owned property in the city were often forced to sell it at a substantial loss or abandon it altogether; the asking price of one particularly impressive house was cut 75 percent within a two-week period.

On 8 April, a South Vietnamese pilot and secret communist, Nguyễn Thành Trung, bombed the Independence Palace and then flew to a PAVN-controlled airstrip; Thiệu was not hurt.

[55][56] As Bien Hoa was falling, Toan fled to Saigon, informing the government that most of the top ARVN leadership had virtually resigned themselves to defeat.

This plan was altered at a critical time when a South Vietnamese pilot decided to defect, and jettisoned his ordnance along the only runways still in use (which had not yet been destroyed by shelling).

Under pressure from Kissinger, Martin forced Marine guards to take him to Tan Son Nhat in the midst of continued shelling, so he might personally assess the situation.

"Lady Ace 09" from USMC squadron HMM-165 and piloted by Berry, took off at 04:58—though he didn't know it, had Martin refused to leave, the Marines had a reserve order to arrest him and carry him away to ensure his safety.

[69] Martin was flown out to the USS Blue Ridge, where he pleaded for helicopters to return to the embassy compound to pick up the few hundred remaining hopefuls waiting to be evacuated.

Although his pleas were overruled by Ford, Martin was able to convince the Seventh Fleet to remain on station for several days so any locals who could make their way to sea via boat or aircraft might be rescued by the waiting Americans.

[citation needed] Many Vietnamese nationals who were evacuated were allowed to enter the United States under the Indochina Migration and Refugee Assistance Act.

The historic staircase that led to the rooftop helicopter pad in the nearby apartment building used by the CIA and other U.S. government employees was salvaged and is on permanent display at the Gerald R. Ford Museum in Grand Rapids, Michigan.

The ARVN 3rd Task Force, 81st Ranger Group commanded by Major Pham Chau Tai defended Tan Son Nhut and they were joined by the remnants of the Loi Ho unit.

At 07:15 on 30 April, the PAVN 24th Regiment approached the Bay Hien intersection (10°47′35″N 106°39′11″E / 10.793°N 106.653°E / 10.793; 106.653) 1.5 km from the main gate of Tan Son Nhat Air Base.

The PAVN 10th Division ordered eight more tanks and another infantry battalion to join the attack, but as they approached the Bay Hien intersection they were hit by an airstrike from RVNAF jets operating from Binh Thuy Air Base which destroyed two T-54s.

[76] At approximately 10:30 Pham at Tan Son Nhut Air Base heard of the surrender broadcast and went to the Joint General Staff Compound to seek instructions.

The Viet Cong machinery in South Vietnam was weakened, owing in part to the Phoenix Program, so the PAVN was responsible for maintaining order and General Trần Văn Trà, Dũng's administrative deputy, was placed in charge of the city.

[93] Following the end of the war, according to official and non-official estimates, between 200,000 and 300,000 South Vietnamese were sent to re-education camps, where many endured torture, starvation, and disease while they were being forced to do hard labor.

[citation needed] The U.S. State Department estimated that the Vietnamese employees of the U.S. Embassy in South Vietnam, past and present, and their families totaled 90,000 people.