Khosrow and Shirin

It tells a highly elaborated fictional version of the story of the love of Khosrow II for the Christian Shirin, who became the queen consort of the Sasanian Empire.

The two lovers keep travelling to opposite places until Khosrow is overthrown by a general named Bahrām Chobin and flees to Armenia.

Khosrow cannot abide Farhad, so he sends him as an exile to Behistun mountain with the impossible task of carving stairs out of the cliff rocks.

Khosrow, before proposing marriage to Shirin, tries to get intimate with another woman named Shekar in Isfahan, which further delays the lovers' union.

There are many references to the legend throughout the poetry of other Persian poets including Farrokhi, Qatran, Mas'ud-e Sa'd-e Salman, Othman Mokhtari, Naser Khusraw, Anwari and Sanai.

The story has a constant forward drive with exposition, challenge, mystery, crisis, climax, resolution, and finally, catastrophe.

Besides Ferdowsi, Nizami's poem was influenced by Asad Gorgani and his "Vis and Rāmin",[8] which is of the same meter and has similar scenes.

According to the Encyclopædia Iranica: "The influence of the legend of Farhad is not limited to literature, but permeates the whole of Persian culture, including folklore and the fine arts.

"[6] In 2011, the Iranian government's censors refused permission for a publishing house to reprint the centuries-old classic poem that had been a much-loved component of Persian literature for 831 years.

While the Iranian Ministry of Culture and Islamic Guidance offered no immediate official explanation for refusing to permit the firm to publish their eighth edition of the classic, the Islamic government's concerns reportedly centered on the "indecent" act of the heroine, Shirin, in embracing her husband.

[9] Orhan Pamuk's novel My Name Is Red (1998) has a plot line between two characters, Shekure and Black, which echoes the Khosrow and Shirin story, which is also retold in the book.

The tale was also an inspiration for the 2012 Bollywood romantic comedy film, Shirin Farhad Ki Toh Nikal Padi.

[23] These other illustrations are influenced by European styles of art and the variations in text to picture interpretations are reflections of previous artistic deviations from Nizami's story.

The illustrated copy of Hatifi's poem dates from the reign of the Ottoman sultan Bayezid II, a celebrated patron of the arts.

[24] The colophon indicates that the author, who went by the pseudonym Sūzī, meaning "burning one", [25]copied the entire text as well as painted the illustrations by themselves.

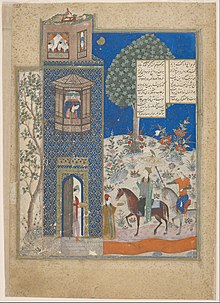

The manuscript starts with a double frontispiece that resembles the first pages in luxury Qur'ans produced at the time, albeit less elaborate (figure 1).

The balconies and curved, leaded roofs of the palace building exemplify the Ottoman architectural style, as do the arched openings and iron grilles on the garden walls.

This incorporation of realism is distinctly Ottoman, with Persian art styles typically foregrounding idealism and romanticism.

The variations in depictions of the same scene demonstrate influences of other art styles and stylistic choices of each illustrator.

In Nizami's text, Khosrow accidentally sees Shīrīn bathing when he rides by a pool of water in disguise.

One depiction of the scene hangs in the Seattle Art Museum and is titled Khusraw Discovers Shirin Bathing in a Pool.

There is a sense of intimacy in this scene due to the languid way Shīrīn's clothes hang from the tree branch.

A second illustration, titled Khusrau Catches Sight of Shirin Bathing, by Shaikh Zada is from 1524 CE (figure 4).

Art historian, Abolala Soudavar, believes that Khusrau is actually a portrait of Hosayn Khān, the patron of the manuscript for which this illustration was produced.

[31] Its materials are similar to Murshid al-Shirazi's illustration and include watercolor, ink, and gold on paper.

A fourth painting of the scene, titled Khusraw Discovers Shirin Bathing, comes from an unknown artist from the 18th century.

Khosrow is in his princely attire, rather than in disguise, and Shīrīn's horse is silver and brown, instead of black (figure 6) .

However, the painter of this miniature decided to add three extra people to the scene, disrupting the intimacy between the two lovers in the text.

[32] Although the lack of perspective in the illustration is a sign of Persian miniature art style,[33] the muted colors, use of chiaroscuro, and materials (oil on canvas) all show the influence of European artistry.

[35] A depiction of the same scene, from the rare books department of the Free Library of Philadelphia, has the same overall structure as that of the Princeton illustration (figure 7).