Fearsome critters

Fearsome critters were an integral part of oral tradition in North American logging camps during the turn of the twentieth century,[1] principally as a means to pass time (such as in tall tales)[4] or as a jest for hazing newcomers.

[5] In a typical fearsome critter gag, a person would casually remark about a strange noise or sight they encountered in the wild, and another accomplice would join in with a similar anecdote.

Meanwhile, an eavesdropper would begin to investigate, as Henry H. Tryon recorded in his book, Fearsome Critters (1939) — Sam would lead with a colorful bit of description, and Walter would follow suit with an arresting spot of personal experience, every detail being set forth with the utmost solemnity, and with exactly the correct degree of emphasis.

The mangrove killifish, which takes up shelter in decaying branches after leaving the water,[8] exhibits similarities to the upland trout, a legendary fish purported to nest in trees.

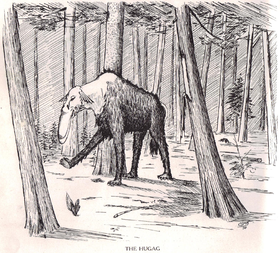

Both the tripodero[6] and snoligoster[4] demonstrate facets more in common with mechanical apparatuses than animals, and the hugag and sidehill gouger[5] seem to be more a play on applied physics than fanciful inspiration.

For instance, in Henry H. Tryon's Fearsome Critters, the wampus cat is described as having pantographic forelimbs[5] while in Vance Randolph's We Always Lie to Strangers, it is portrayed as a supernatural, aquatic panther.

In his 1939 book, Fearsome Critters, Henry H. Tryon recounted that "... much true folk-lore was born, lived and died with no chance of ever becoming a part of our permanent records.