Feudalism in the Holy Roman Empire

[citation needed] Feudalism in Europe emerged in the Early Middle Ages, based on Roman clientship and the Germanic social hierarchy of lords and retainers.

In turn, they could award fiefs to other nobles, who wanted to be enfeoffed by them and who were often subordinate to the liege lord in the aristocratic hierarchy.

A fief (also fee, feu, feud, tenure or fiefdom, German: Lehen, Latin: feudum, feodum or beneficium) was understood to be a thing (land, property), which its owner, the liege lord (Lehnsherr), had transferred to the hereditary ownership of the beneficiary on the basis of mutual loyalty, with the proviso that it would return to the lord under certain circumstances.

Enfeoffment gave the vassal extensive, hereditary usufruct of the fief, founded and maintained on a relationship of mutual loyalty between the lord and the beneficiary.

The beneficiary was his vassal, liegeman or feudatory (German: Vasall, Lehnsmann, Knecht, Lehenempfänger or Lehensträger; Latin: vassus or vasallus).

During the latter years of the period of clan society with Germanic kingdoms on Roman soil, it was common for all the land to belong to the king.

Over time, a practice developed that the person enfeoffed with the land, together with his family, became the beneficiaries of the fief and remained permanently bound to it.

This means that, in the event of war, they had to provide soldiers and assistance, or if money ran short or a ransom was needed, they were expected to support the king.

The enforcement of Lehnsrecht is associated with the reduced circulation of money in the Late Antiquity and Early Medieval periods.

The handgang, which together with the oath of loyalty (Treueid), became referred to as homagium (Latin), homage (French), or mannschaft (German), became the decisive legal device until well into the 12th century.

Counts and bishops still functioned as royal appointees rather than hereditary lords, and it was still common for the peasants to be free tenants or freeholders instead of serfs.

However, with the civil wars in the reign of Henry IV and the suppression of the Duchy of Saxony by Frederick Barbarossa, the Holy Roman Empire rapidly fragmented into feudal estates.

Not until the 13th century, did the importance of the feudal system decline, because instead of vassals (Vassallen), liegemen (Dienstmannen) - well-educated men (c.f.

The kings encouraged this development, for political reasons, and so strengthened territorial lordship (Landesherrschaft), which replaced the feudal system empire-wide.

This strengthening of territorial rulers had an impact that could not be reversed, so that the power of the various principalities did not reduce, unlike the situation in France and England.

Legally, it was abolished inter alia by the Confederation of the Rhine acts, in the Final Recess of the Reichsdeputation and the Frankfurt Constitution of 1849.

One of the last fiefs was awarded in 1835, when the ailing Count Friedrich Wilhelm von Schlitz, known as Görtz, was enfeoffed with the spring at Salzschlirf and began to excavate it again.

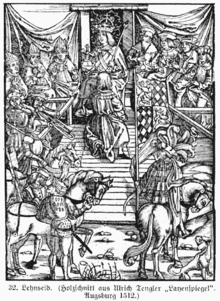

Feoffment (constitutio feudi, infeudatio) involved the vassal being formally seized of his fief through a commendation ceremony.

From the end of the 9th century, this act was expanded to include an oath of allegiance, which was usually sworn on a religious relic.

As literacy rose, a charter of feoffment was also made out as part of the act that, over time, listed the feoffed estate and benefits that the vassal was to receive in ever increasing detail.

In the late Middle Ages, an entry fee was demanded for feoffment, which was often based on the fief's annual income.

Sometimes the vassal even sold or gifted over his possessions to the lord (Lehnsauftragung) and then received it back as a fief (oblatio feudi).

The lord purchased or accepted the gift because he might have the intention or hope, for example, of merging unrelated fiefdoms into a whole and thus extending his sphere of influence, for example, in terms of jurisdiction, or the appointment of clergy.

This could be unlimited, i.e. the vassal had to assist his lord in every conflict, or it could be limited in time, space and in the number of troops to be raised.

With the advent of the mercenaries, the reliance on vassals became less important and their service increasingly took the form of administration and court duties.

Depending on local law, the vassal might be liable, apart from the fee, for the renewal of the enfeoffment (called the Schreibschilling or Lehnstaxe), to pay a special tax (the Laudemium, Lehnsgeld, Lehnsware or Handlohn).

Finally, in the event of a felony by the vassal, the lord could confiscate the fief under the so-called Privationsklage action or step in to prevent the deterioration of the estate, if necessary, by legal means.

In central Europe, kings and counts probably were willing to allow the inheritance of small parcels of land to the heirs of those who had offered military or other services in exchange for tenancy.

The Bishop of Worms issued a statement in 1120 indicating the poor and unfree should be allowed to inherit tenancy without payment of fees.

Also, the opportunity to inherit a fief diminished the ability of the lord to intervene and loosened the personal loyalty of liegemen.