Finger

A finger is a prominent digit on the forelimbs of most tetrapod vertebrate animals, especially those with prehensile extremities (i.e. hands) such as humans and other primates.

In humans, the fingers are flexibly articulated and opposable, serving as an important organ of tactile sensation and fine movements, which are crucial to the dexterity of the hands and the ability to grasp and manipulate objects.

Within the taxa of the terrestrial vertebrates, the basic pentadactyl plan, and thus also the metacarpals and phalanges, undergo many variations.

[7] Research has been carried out on the embryonic development of domestic chickens showing that an interdigital webbing forms between the tissues that become the toes, which subsequently regresses by apoptosis.

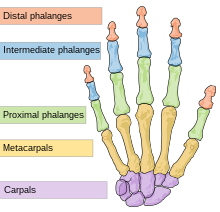

[8][9][10] Usually humans have five digits,[11] the bones of which are termed phalanges,[2] on each hand, although some people have more or fewer than five due to congenital disorders such as polydactyly or oligodactyly, or accidental or intentional amputations.

Each of the fingers has three joints: Sesamoid bones are small ossified nodes embedded in the tendons to provide extra leverage and reduce pressure on the underlying tissue.

The muscle bulks that move each finger may be partly blended, and the tendons may be attached to each other by a net of fibrous tissue, preventing completely free movement.

The long tendons that deliver motion from the forearm muscles may be observed to move under the skin at the wrist and on the back of the hand.

The lumbricals arise from the deep flexor (and are special because they have no bony origin) and insert on the dorsal extensor hood mechanism.

Aside from the genitals, the fingertips possess the highest concentration of touch receptors and thermoreceptors among all areas of the human skin,[17] making them extremely sensitive to temperature, pressure, vibration, texture and moisture.

A study in 2013 suggested fingers can feel nano-scale wrinkles on a seemingly smooth surface, a level of sensitivity not previously recorded.

[19] Although a common phenomenon, the underlying functions and mechanism of fingertip wrinkling following immersion in water are relatively unexplored.

[23] However, a 2014 study attempting to reproduce these results was unable to demonstrate any improvement of handling wet objects with wrinkled fingertips.

This works because the distal phalanges are regenerative in youth, and stem cells in the nails create new tissue that ends up as the fingertip.

[29] A rare anatomical variation affects 1 in 500 humans, in which the individual has more than the usual number of digits; this is known as polydactyly.

A damaged tendon can cause significant loss of function in fine motor control, such as with a mallet finger.

Raynaud's phenomenon and Paroxysmal hand hematoma are neurovascular disorders that affect the fingers.

Linguists generally assume that *fingraz is a ro-stem deriving from a previous form *fimfe, ultimately from Proto-Indo-European *pénkʷe ('five').