History of Finland

[2] Due to the Northern Crusades and Swedish colonisation of some Finnish coastal areas, most of the region became a part of the Kingdom of Sweden and the realm of the Catholic Church from the 13th century onwards.

[10] In recent years, a dig at the Kierikki site north of Oulu on the River Ii has changed the image of Finnish neolithic Stone Age culture.

Numerous other sources from the Roman period onwards contain brief mentions of ancient Finnish kings and place names, as such defining Finland as a kingdom and noting the culture of its people.

[17] However, as the long continuum of the Finnish Iron Age into the historical Medieval period of Europe suggests, the primary source of information of the era in Finland is based on archaeological findings[14] and modern applications of natural scientific methods like those of DNA analysis[18] or computer linguistics.

[14] The Migration period saw the expansion of land cultivation inland, especially in Southern Bothnia, and the growing influence of Germanic cultures, both in artifacts like swords and other weapons and in burial customs.

[14] The Merovingian period in Finland gave rise to a distinctive fine crafts culture of its own, visible in the original decorations of domestically produced weapons and jewelry.

It was for a long time widely[dubious – discuss] believed[19][20][21] that Finno-Ugric (the western branch of the Uralic) languages were first spoken in Finland and the adjacent areas during the Comb Ceramic period, around 4000 BC at the latest.

Artifacts found in Kalanti and the province of Satakunta, which have long been monolingually Finnish, and their place names have made several scholars argue for an existence of a proto-Germanic speaking population component a little later, during the Early and Middle Iron Age.

From 1611 to 1632, Sweden was ruled by King Gustavus Adolphus, whose military reforms transformed the Swedish army from a peasant militia into an efficient fighting machine, possibly the best in Europe.

In 1630, the Swedish (and Finnish) armies marched into Central Europe, as Sweden had decided to take part in the great struggle between Protestant and Catholic forces in Germany, known as the Thirty Years' War.

[47] The rigorous requirements of orthodoxy were revealed in the dismissal of the Bishop of Turku, Johan Terserus, who wrote a catechism which was decreed heretical in 1664 by the theologians of the academy of Åbo.

A combination of an early frost, the freezing temperatures preventing grain from reaching Finnish ports, and a lackluster response from the Swedish government saw about one-third of the population die.

However, during the Lesser Wrath (1741–1742), Finland was again occupied by the Russians after the government, during a period of Hat party dominance, had made a botched attempt to reconquer the lost provinces.

The integrity and the credibility of the political system waned, and in 1771 the young and charismatic king Gustav III staged a coup d'état, abolished parliamentarism and reinstated royal power in Sweden—more or less with the support of the parliament.

At the turn of the 19th century, the Swedish-speaking educated classes of officers, clerics and civil servants were mentally well prepared for a shift of allegiance to the strong Russian Empire.

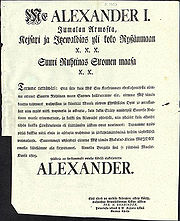

Meanwhile, the Finnish areas belonging to Russia after the peace treaties in 1721 and 1743 (not including Ingria), called "Old Finland", were initially governed with the old Swedish laws (a not uncommon practice in the expanding Russian Empire in the 18th century).

However, gradually the rulers of Russia granted large estates of land to their non-Finnish favorites, ignoring the traditional landownership and peasant freedom laws of Old Finland.

Snellman sought to apply philosophy to social action and moved the basis of Finnish nationalism to establishment of the language in the schools, while remaining loyal to the czar.

Finland considered the personal union with Russia to be over after the dethroning of the Tsar—although the Finns had de facto recognized the Provisional government as the Tsar's successor by accepting its authority to appoint a new Governor General and Senate.

The suppression of the Power Act, and the cooperation between Finnish non-Socialists and Russia provoked great bitterness among the Socialists, and had resulted in dozens of politically motivated attacks and murders.

After the civil war, the parliament controlled by the Whites voted to establish a constitutional monarchy to be called the Kingdom of Finland, with German prince Frederick Charles of Hesse as king.

[90] Finland managed to defend its democracy, contrary to most other countries within the Soviet sphere of influence, and suffered comparably limited losses in terms of civilian lives and property.

Gripenberg (1956–1959), followed by Ralph Enckell (1959–1965), Max Jakobson (1965–1972), Aarno Karhilo (1972–1977), Ilkka Pastinen (1977–1983), Keijo Korhonen (1983–1988), Klaus Törnudd (1988–1991), Wilhelm Breitenstein (1991–1998) and Marjatta Rasi (1998–2005).

Officially claiming to be neutral, Finland lay in the grey zone between the Western countries and the Soviet Union, and it also developed into one of the centres of the East-West espionage, in which both the KGB and the CIA played their parts.

Local education markets expanded and an increasing number of Finns also went abroad to study in the United States or Western Europe, bringing back advanced skills.

[105] Building on its status as western democratic country with friendly ties with the Soviet Union, Finland pushed to reduce the political and military tensions of cold war.

[106] When baby boomers entered the workforce, the economy did not generate jobs fast enough and hundreds of thousands emigrated to the more industrialized Sweden, migration peaking in 1969 and 1970 (today 4.7 percent of Swedes speak Finnish).

Causes of change included the growth of a mass culture, international standards, social mobility, and acceptance of democracy and equality as typified by the welfare state.

[108] The generous system of welfare benefits emerged from a long process of debate, negotiations and maneuvers between efficiency-oriented modernizers on the one hand and Social Democrats and labor unions.

On 25 February, a Russian Foreign Ministry spokesperson threatened Finland and Sweden with "military and political consequences" if they attempted to join NATO, which neither were actively seeking.