History of Poland

The roots of Polish history can be traced to ancient times, when the territory of present-day Poland was inhabited by diverse ethnic groups, including Celts, Scythians, Sarmatians, Slavs, Balts and Germanic peoples.

The period of the Jagiellonian dynasty in the 14th–16th centuries brought close ties with the Lithuania, a cultural Renaissance in Poland and continued territorial expansion as well as Polonization that culminated in the establishment of the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth in 1569, one of Europe's great powers.

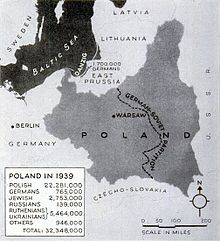

The territorial adjustments mandated by the Allies at the end of World War II in 1945 shifted Poland's geographic centre of gravity towards the west, and the re-defined Polish lands largely lost their historic multi-ethnic character.

[36] The Polish–Lithuanian partnership brought vast areas of Ruthenia controlled by the Grand Duchy of Lithuania into Poland's sphere of influence and proved beneficial for the nationals of both countries, who coexisted and cooperated in one of the largest political entities in Europe for the next four centuries.

This agreement transferred Ukraine from the Grand Duchy of Lithuania to Poland and transformed the Polish–Lithuanian polity into a real union,[36] preserving it beyond the death of the childless Sigismund II, whose active involvement made the completion of this process possible.

The Kingdom of Prussia became a strong regional power and succeeded in wresting the historically Polish province of Silesia from the Habsburg monarchy in the Silesian Wars; it thus constituted an ever-greater threat to Poland's security[improper synthesis?].

The reform activity, initially promoted by the magnate Czartoryski family faction known as the Familia, provoked a hostile reaction and military response from neighboring powers, but it did create conditions that fostered economic improvement.

[60] The royal election of 1764 resulted in the elevation of Stanisław August Poniatowski,[61] a refined and worldly aristocrat connected to the Czartoryski family, but hand-picked and imposed by Empress Catherine the Great of Russia, who expected him to be her obedient follower.

In order to cripple the manpower potential of the Reds, Aleksander Wielopolski, the conservative leader of the government of Congress Poland, arranged for a partial selective conscription of young Poles for the Russian army in the years 1862 and 1863.

[77][78] On 2 March 1864, the Russian authority, compelled by the uprising to compete for the loyalty of Polish peasants, officially published an enfranchisement decree in Congress Poland along the lines of an earlier land reform proclamation of the insurgents.

Piłsudski had entertained far-reaching anti-Russian cooperative designs in Eastern Europe, and in 1919 the Polish forces pushed eastward into Lithuania, Belarus and Ukraine by taking advantage of the Russian preoccupation with a civil war, but they were soon confronted with the Soviet westward offensive of 1918–1919.

Lurking on the sidelines was a disgusted army officer corps unwilling to subject itself to civilian control, but ready to follow the retired Piłsudski, who was highly popular with Poles and just as dissatisfied with the Polish system of government as his former colleagues in the military.

According to Norman Davies, the failures of the Sanation government (combined with the objective economic realities) caused a radicalization of the Polish masses by the end of the 1930s, but he warns against drawing parallels with the incomparably more oppressive Nazi Germany or the Stalinist Soviet Union.

[99][152][153][154] In the late 1930s, the exile bloc Front Morges united several major Polish anti-Sanation figures, including Ignacy Paderewski, Władysław Sikorski, Wincenty Witos, Wojciech Korfanty and Józef Haller.

[183] At a time of increasing cooperation between the Western Allies and the Soviet Union in the wake of the Nazi invasion of 1941, the influence of the Polish government-in-exile was seriously diminished by the death of Prime Minister Władysław Sikorski, its most capable leader, in a plane crash on 4 July 1943.

[204] In an attempt to incapacitate Polish society, the Nazis and the Soviets executed tens of thousands of members of the intelligentsia and community leadership during events such as the German AB-Aktion in Poland, Operation Tannenberg and the Katyn massacre.

[220] Many exiled Poles could not return to the country for which they had fought because they belonged to political groups incompatible with the new communist regimes, or because they originated from areas of pre-war eastern Poland that were incorporated into the Soviet Union (see Polish population transfers (1944–1946)).

[230] In the immediate post-war years, the emerging communist rule was challenged by opposition groups, including militarily by the so-called "cursed soldiers", of whom thousands perished in armed confrontations or were pursued by the Ministry of Public Security and executed.

[231] In times of severe political confrontation and radical economic change, members of Mikołajczyk's agrarian movement (the Polish People's Party) attempted to preserve the existing aspects of mixed economy and protect property and other rights.

[243][244][245] The ruling communists, who in post-war Poland preferred to use the term "socialism" instead of "communism" to identify their ideological basis,[246][f] needed to include the socialist junior partner to broaden their appeal, claim greater legitimacy and eliminate competition on the political Left.

Motivated in part by the Prague Spring movement, the Polish opposition leaders, intellectuals, academics and students used a historical-patriotic Dziady theater spectacle series in Warsaw (and its termination forced by the authorities) as a springboard for protests, which soon spread to other centers of higher education and turned nationwide.

[281] In the final major achievement of Gomułka diplomacy, the governments of Poland and West Germany signed in December 1970 the Treaty of Warsaw, which normalized their relations and made possible meaningful cooperation in a number of areas of bilateral interest.

[288] Fueled by large infusions of Western credit, Poland's economic growth rate was one of the world's highest during the first half of the 1970s, but much of the borrowed capital was misspent, and the centrally planned economy was unable to use the new resources effectively.

[295] The United States, under presidents Jimmy Carter and Ronald Reagan, repeatedly warned the Soviets about the consequences of a direct intervention, while discouraging an open insurrection in Poland and signaling to the Polish opposition that there would be no rescue by the NATO forces.

[304] The fitful bargaining and intra-party squabbling led to the official Round Table Negotiations in 1989, followed by the Polish legislative election in June of that year, a watershed event marking the fall of communism in Poland.

[356][357] According to the historians Czesław Brzoza and Andrzej Leon Sowa, orders of further military offensives, issued at the end of August 1944 as a continuation of Operation Tempest, show a loss of the sense of responsibility for the country's fate on the part of the underground Polish leadership.

Military raids, public beatings, property confiscations and the closing and destruction of Orthodox churches aroused lasting enmity in Galicia and antagonized Ukrainian society in Volhynia at the worst possible moment, according to Timothy D. Snyder.

The inability of Polish kings to levy and collect taxes (and therefore sustain a standing army) and conduct independent foreign policy were among the chief obstacles to Poland competing effectively on the changed European scene, where absolutist power was a prerequisite for survival and became the foundation for the abolition of serfdom and gradual formation of parliamentarism.

According to this view, the Lusatian Culture, which flourished between the Oder and the Vistula in the early Iron Age, was said to be Slavonic; all non-Slavonic tribes and peoples recorded in the area at various points in ancient times were dismissed as "migrants" and "visitors".

In contrast, the critics of this theory, such as Marija Gimbutas, regarded it as an unproved hypotheses and for them the date and origin of the westward migration of the Slavs were largely uncharted; the Slavonic connections of the Lusatian Culture were entirely imaginary; and the presence of an ethnically mixed and constantly changing collection of peoples on the North European Plain was taken for granted.