First-wave feminism

[1] The term first-wave feminism itself was coined by journalist Martha Lear in a New York Times Magazine article in March 1968, "The Second Feminist Wave: What do these women want?

[5] The wave metaphor is well established, including in academic literature, but has been criticized for creating a narrow view of women's liberation that erases the lineage of activism and focuses on specific visible actors.

The issues of inclusion that began during the first-wave of the feminist movement in the United States and persisted throughout subsequent waves of feminism are the topic of much discussion on an academic level.

Well known European, Latin, and North American workers, intellectuals, thinkers and professionals like Marie Curie, Emilia Pardo Bazán, Ellen Key, Maria Montessori and many others presented and discussed their ideas research work and studies on themes of gender, political and civil right, divorce, economy, education, health and culture.

In 1882, Rose Scott, a women's rights activist, began to hold weekly salon meetings in her Sydney home left to her by her late mother.

[31] The First wave women's movement in France organized when the Association pour le Droit des Femmes was founded by Maria Deraismes and Léon Richer in 1870.

Wilhelmina Drucker (1847–1925) was a politician, a prolific writer and a peace activist, who fought for the vote and equal rights through political and feminist organisations she founded.

Selma Meyer (1890–1941), Secretary of the Dutch Women's International League for Peace and Freedom [WILPF] Early New Zealand feminists and suffragettes included Maud Pember Reeves (Australian-born; later lived in London), Kate Sheppard and Mary Ann Müller.

[37] Feminist issues and gender roles were discussed in media and literature during the 18th century by people such as Margareta Momma, Catharina Ahlgren, Anna Maria Rückerschöld and Hedvig Charlotta Nordenflycht, but it created no movement of any kind.

The first person to hold public speeches and agitate in favor of feminism was Sophie Sager in 1848,[38] and the first organization created to deal with a women's issue was Svenska lärarinnors pensionsförening (Society for Retired Female Teachers) by Josefina Deland in 1855.

Antoinette Burton writes that rather than upending Victorian gendered assumptions, "early feminist theorist used [them] to justify female involvement in the public sphere by claiming that the woman's moral attributes was crucial to social improvement.

"[58] Burton calls to our attention that women exerted real power over their male counterparts by making claims to the very moral assumptions that bound them to the home.

It would be naïve to suggest that these women were not complicit in or did not contribute to imperial oppression abroad, but what is missed by previous treatments of feminisms and feminist movements is the diversity and flexibility of power relationships that navigated the superstructure of the moral order.

[61] Leading up to the early 19th century, white women in Colonial America were socially expected to remain domestically confined and their property and political rights were severely limited and controlled by marriage.

Thus the impact of alcohol on many men post Civil War became not only a moral motivation for women to become active in the Temperance Movement but also a way to exert control over finances and property.

Judith Sargent Murray published the early and influential essay On the Equality of the Sexes in 1790, blaming poor standards in female education as the root of women's problems.

[64] However, scandals surrounding the personal lives of English contemporaries Catharine Macaulay and Mary Wollstonecraft pushed feminist authorship into private correspondence from the 1790s through the early decades of the nineteenth century.

[65] Feminist essays from John Neal in Blackwood's Magazine and The Yankee in the 1820s filled an intellectual gap between Murray and the leaders of the 1848 Seneca Falls Convention,[66] which is generally considered the beginning of the first wave of feminism.

[67] As a male writer insulated from many common forms of attack against female feminist thinkers, Neal's advocacy was crucial to bringing feminism back into the American mainstream.

Other important leaders included several women who dissented against the law in order to have their voices heard, (Sarah and Angelina Grimké), in addition to other activists such as Carrie Chapman Catt, Alice Paul, Sojourner Truth, Ida B.

The creation of these organizations was a direct result of the Second Great Awakening, a religious movement in the early 19th century, that inspired female reformers in the United States.

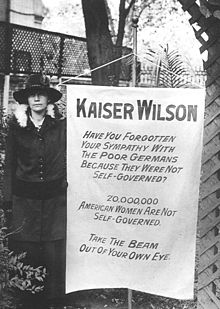

The NWSA was known for having more publicly aggressive tactics (such as picketing and hunger strikes) whereas the AWSA used more traditional strategies like lobbying, delivering speeches, applying political pressure, and gathering signatures for petitions.

Frederick Douglass was heavily involved in both movements and believed that it was essential for both to work together in order to attain true equality in regards to race and sex.

[80] Marylynn Salmon argues that each state developed different ways of dealing with a variety of legal issues pertaining to women, especially in the case of property laws.

Anxiety in the United States over the moral degeneracy and temptation of American men in the Philippines inspired women's involvement in the politics of the colonial government.

An article published in The Washington Post in 1900 describes the Philippines as an environment where relatively permissive conceptions of morality caused white men to "lose all notions of right and wrong".

Black Americans regardless of gender face a violent history of oppression that exploited, abused and commoditized the body for labor as an essential aspect of the early development and success of the United States' economy.

The goal of first-wave feminism being mainly to resolve legal issues, chiefly to secure voting rights, only considered the needs of white high class women.

[99] The National American Woman Suffrage Association, established by Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton[100] did not invite black women to attend specific meetings, excluding them entirely.

"[234] From this perspective, 19th- and early 20th-century feminisms reproduced the very social hierarchies they had the potential to struggle against, exemplifying the claim of Michel Foucault in his The History of Sexuality, Volume I: An Introduction that "resistance is never in a position of exteriority in relation to power.