Old Straight Road

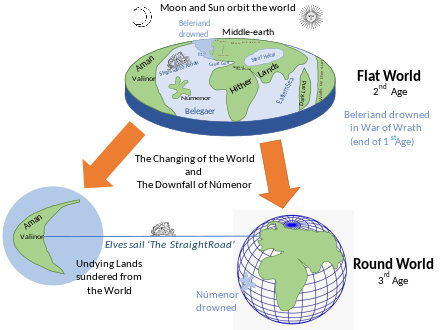

He destroys Númenor and its army, in the process reshaping Arda into a sphere, and separating it and its continent of Middle-earth from Valinor so that men can no longer reach it.

Other possible inspirations for the theme include a novel by John Buchan, and a literary crux in Beowulf in the shape of the character Scyld Scefing.

He arrives in the world as a baby in a boat filled with gifts, and he departs from it in a ship-burial, with the odd feature that the ship is not set on fire, as in the typical Viking ritual.

When Ar-Pharazôn landed, Ilúvatar destroyed his forces and sent a great wave to submerge Númenor, killing all but those Númenóreans, led by Elendil, who had remained loyal to the Valar, and who escaped to Middle-earth.

And of old many of the Númenóreans could see or half see the paths of the True West, ... [able perhaps to make out] the peaks of Taniquetil at the end of the straight road, high above the world.

[T 4]Tolkien made two attempts at a time travel novel, both remaining unfinished: first in the 1936 The Lost Road,[T 5] and then in 1945 The Notion Club Papers.

Tom Shippey writes that Tolkien's personal First World War experience was Manichean: evil seemed at least as powerful as good, and could easily have been victorious, a strand which can also be seen in Middle-earth.

The two time travel novels both foundered on the problem that while they made perfect sense to him as frame stories, which he worked out in some detail, this was at the expense of their actual narratives, which he never got around to writing.

[7] Verlyn Flieger writes that Tolkien's essay "Beowulf: the Monsters and the Critics", his "On Fairy-Stories", and The Lost Road all indicate his "desire to pass through that open door into Other Time.

[10] Beowulf, an Anglo-Saxon poem that Tolkien knew well, contains, among its cruxes, its unexplained or problematic passages, a mention at the start of Scyld Scefing.

[7] Dimitra Fimi notes that Beowulf (lines 26–52) describes Scyld's funeral ship sailing "on its own accord" to its unknown harbour.

Shippey notes that the pronoun þā ("those") is, unusually for such an insignificant part of speech, both stressed and alliterated, a heavy emphasis (marked in the text):[7] Nalæs hī hine lǣssan / lācum tēodan, þeodgestrēonum, / þon þā dydon þē hine æt frumsceafte / forð onsendon ǣnne ofer ǣðe / umborwesende.

þā gǣt hīe him āsetton / segen geldenne hēah ofer hēafod, / lēton holm beran, gēafon on gārsecg; / him wæs geōmor sefa, murnende mōd.

Then yet they set up / standard golden high over head, / they let sea carry, gave to ocean; / in them was gloomy heart, mourning mind.

In The Lost Road and Other Writings, Christopher Tolkien quotes from one of his father's lectures: "the [Beowulf] poet is not explicit, and the idea was probably not fully formed in his mind—that Scyld went back to some mysterious land whence he had come.

[14] The level bridge "imperceptibly" departs from the earth at a tangent, but enough of the earlier cosmology remains "in the mind of the Gods" for the Elves and the Valar to be able to travel that Straight Road.

[15] John Garth similarly states that while the Straight Road linking Valinor with Middle-Earth after the Second Age mirrors Bifröst, the Valar themselves resemble the Æsir, the gods of Asgard.

[17] Fimi was surprised that Tolkien apparently linked immram in the shape of St. Brendan's voyages to Ælfwine's journey into the uttermost West, and went on doing so.

[18][19] The Tolkien scholar David Bratman writes that there is a recurring theme of locale in her fantasy stories, especially in her 1985 novel, Always Coming Home.