First aerial circumnavigation

[1] The team generally traveled east to west, around the northern Pacific Rim, through to South Asia and Europe and back to Seattle's Sand Point Airfield in the United States.

Airmen Lowell H. Smith and Leslie P. Arnold, and Erik H. Nelson and John Harding Jr. made the trip in two single-engined open-cockpit Douglas World Cruisers (DWC) configured as floatplanes for most of the journey.

[3]: 4 The War Department instructed the Air Service to look at both the Fokker T-2 transport and the Davis-Douglas Cloudster to see if either would be suitable and to acquire examples for testing.

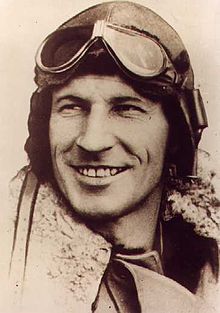

The Air Service agreed and sent Lieutenant Erik Henning Nelson (1888–1970), a member of the planning group, to California to work out the details with Douglas.

Shortly after departing Prince Rupert Island on 15 April, the lead aircraft Seattle, flown by Martin with Harvey (the only fully qualified mechanic in the flight), blew a 3-inch (8 cm) hole in its crankcase and was forced to land on Portage Bay.

[N 3] Tracing the Aleutian Islands, the flight traveled across the North Pacific, landing in the Soviet Union notwithstanding the lack of entry permission.

After leaving Haiphong in the Gulf of Tonkin, the Chicago's engine broke a connecting rod and it was forced to land in a lagoon near Huế.

The aircraft was considered a novelty in this region and missionary priests supplied the pilots with food and wine while locals climbed aboard its pontoons.

The other flyers, who had continued on to Tourane (Da Nang), searched for Chicago by boat and found the crew sitting on the wing in the early morning hours.

[3]: 190 After carrying out the major operation of exchanging the Cruisers' floats for wheeled undercarriage at Calcutta, on the evening of 29 June Smith, in the dark after dinner, slipped and broke a rib.

From Paris the aircraft flew to London and on to the north of England in order to prepare for the Atlantic Ocean crossing by re-installing pontoons and changing engines.

The accompanying Chicago flew on to the Faroes where it dropped a note onto the supporting U.S. Navy light cruiser USS Richmond about the troubled aircraft.

After a long stay in Reykjavík, Iceland, where they met Italian Antonio Locatelli and his crew, also in the course of a circumnavigation attempt, and there accompanied by five navy vessels and their 2,500 seaman, Chicago, with Smith and Arnold still in the lead, and the New Orleans, with Nelson and Harding, continued for Fredricksdal, Greenland.

[17] The trip had taken 363 flying hours 7 minutes, over 175 calendar days, and covered 26,345 miles (42,398 km),[3]: 315 [2] succeeding where the British, Portuguese,[24] French, Italians and Argentinians failed.

[25][N 4] The American team had greatly increased their chances of success by using several aircraft and pre-positioning large caches of fuel, spare parts, and other support equipment along the route.

In 1974, Chicago was restored under the direction of Walter Roderick,[29] and transferred to the new National Air and Space Museum building for display in their Barron Hilton Pioneers of Flight exhibition gallery.

Nelson rose to the rank of colonel and became one of General Henry Arnold's chief trouble-shooters on the development and operational deployment of the Boeing B-29 Superfortress.

The first aerial circumnavigation of the world that involved the crossing of the equator twice occurred from 1928 to 1930, and was made using a single aircraft, the Southern Cross, a Fokker F.VII trimotor monoplane[36] crewed by Charles Kingsford Smith (lead pilot), Charles Ulm (relief pilot), James Warner (radio operator), and Harry Lyon (navigator and engineer).

[37] They flew the Southern Cross to England in June 1929, then across the Atlantic and North America, returning, in 1930, to Oakland where their 1928 trans-Pacific flight had begun.