Five precepts

In countries where Buddhism had to compete with other religions, such as China, the ritual of undertaking the five precepts developed into an initiation ceremony to become a Buddhist layperson.

[29] The five precepts are also partly found in the teaching called the ten good courses of action, referred to in Theravāda (Pali: dasa-kusala-kammapatha) and Tibetan Buddhism (Sanskrit: daśa-kuśala-karmapatha; Wylie: dge ba bcu).

[31] In conclusion, the five precepts lie at the foundation of all Buddhist practice, and in that respect, can be compared with the Ten Commandments in Christianity and Judaism[6][7] or the ethical codes of Confucianism.

[37] The prohibition on killing had motivated early Buddhists to form a stance against animal sacrifice, a common religious ritual practice in ancient India.

Lastly, the precepts, together with the triple gem, become a required condition for the practice of Buddhism, as laypeople have to undergo a formal initiation to become a member of the Buddhist religion.

In countries in which Buddhism was adopted as the main religion without much competition from other religious disciplines, such as Thailand, the relation between the initiation of a layperson and the five precepts has been virtually non-existent.

[43][44] These strict attitudes were formed partly because of the religious writings, but may also have been affected by the bloody An Lushan Rebellion of 775, which had a sobering effect on 8th-century Chinese society.

)[51]The format of the ceremony for taking the precepts occurs several times in the Chinese Buddhist Canon, in slightly different forms.

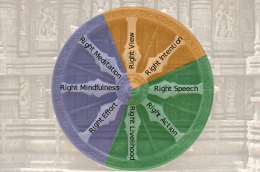

[60] The precepts are normative rules, but are formulated and understood as "undertakings"[61] rather than commandments enforced by a moral authority,[62][63] according to the voluntary and gradualist standards of Buddhist ethics.

[70] Ethicist Pinit Ratanakul argues that the compassion which motivates upholding the precepts comes from an understanding that all living beings are equal and of a nature that they are 'not-self' (Pali: anattā).

[80][83] For example, anthropologist Stanley Tambiah found in his field studies that strict observance of the precepts had "little positive interest for the villager ... not because he devalues them but because they are not normally open to him".

Scholar of religion Richard Jones concludes that the moral motives of Buddhists in adhering to the precepts are based on the idea that renouncing self-service, ironically, serves oneself.

[94] Several modern teachers such as Thich Nhat Hanh and Sulak Sivaraksa have written about the five precepts in a wider scope, with regard to social and institutional relations.

[111] Asian studies scholar Giulio Agostini argues, however, that Buddhist commentators in India from the 4th century onward thought abortion did not break the precepts under certain circumstances.

Buddhologist André Bareau points out that the Buddha was reserved in his involvement of the details of administrative policy, and concentrated on the moral and spiritual development of his disciples instead.

[50][99] In some traditional communities, such as in Kandal Province in pre-war Cambodia, as well as Burma in the 1980s, it was uncommon for Buddhists to slaughter animals, to the extent that meat had to be bought from non-Buddhists.

[123] In modern times, referring to the law of supply and demand or other principles, some Theravādin Buddhists have attempted to promote vegetarianism as part of the five precepts.

Vietnamese teacher Thich Nhat Hanh gives a list of examples, such as working in the arms industry, the military, police, producing or selling poison or drugs such as alcohol and tobacco.

For example, in the twentieth century, some Japanese Zen teachers wrote in support of violence in war, and some of them argued this should be seen as a means to uphold the first precept.

[128] There is some debate and controversy surrounding the problem whether a person can commit suicide, such as self-immolation, to reduce other people's suffering in the long run, such as in protest to improve a political situation in a country.

[64] Although capital punishment goes against the first precept, as of 2001, many countries in Asia still maintained the death penalty, including Sri Lanka, Thailand, China and Taiwan.

Ethicist Roy W. Perrett, following Ratanakul, argues that this field research data does not so much indicate hypocrisy, but rather points at a "Middle Way" in applying Buddhist doctrine to solve a moral dilemma.

[144][145] In traditional Buddhist societies such as Sri Lanka, pre-marital sex is considered to violate the precept, though this is not always adhered to by people who already intend to marry.

[150] The accompanying virtue is being honest and dependable,[26][102] and involves honesty in work, truthfulness to others, loyalty to superiors and gratitude to benefactors.

[152] Some modern teachers such as Thich Nhat Hanh interpret this to include avoiding spreading false news and uncertain information.

[138] Terwiel reports that among Thai Buddhists, the fourth precept is also seen to be broken when people insinuate, exaggerate or speak abusively or deceitfully.

[81] The fifth precept prohibits intoxication through alcohol, drugs or other means, and its virtues are mindfulness and responsibility,[12][13] applied to food, work, behavior, and with regard to the nature of life.

[166] Furthermore, Buddhist teachers such as Philip Kapleau, Thich Nhat Hanh and Robert Aitken have promoted mindful consumption in the West, based on the five precepts.

Specifically, to prevent organizations from using mindfulness training to further an economical agenda with harmful results to its employees, the economy or the environment, the precepts could be used as a standardized ethical framework.

He argues that human beings do have natural rights from a Buddhist perspective, and refers to the attūpanāyika-dhamma, a teaching in which the Buddha prescribes a kind of Golden Rule of comparing oneself with others (see § Principles, above).