Fizeau experiment

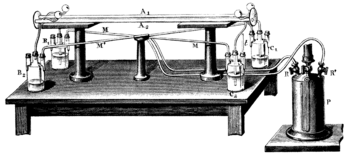

Fizeau used a special interferometer arrangement to measure the effect of movement of a medium upon the speed of light.

His results seemingly supported the partial aether-drag hypothesis of Augustin-Jean Fresnel, a situation that was disconcerting to most physicists.

Over half a century passed before a satisfactory explanation of Fizeau's unexpected measurement was developed with the advent of Albert Einstein's theory of special relativity.

Einstein later pointed out the importance of the experiment for special relativity, in which it corresponds to the relativistic velocity-addition formula when restricted to small velocities.

As scientists in the 1700's worked on a theory of light and of electromagnetism, luminiferous aether, a medium that would support waves, was the focus of many experiments.

For example, astronomical aberration, the apparent motion of stars observed at different times of year, was proposed to be related to starlight propagated through an aether.

This guaranteed that the opposite beams would pass through equivalent paths, so that fringes readily formed even when using the sun as a light source.

The double transit of the light was for the purpose of augmenting the distance traversed in the medium in motion, and further to compensate entirely any accidental difference of temperature or pressure between the two tubes, from which might result a displacement of the fringes, which would be mingled with the displacement which the motion alone would have produced; and thus have rendered the observation of it uncertain.

After passing back and forth through the tubes, both rays unite at S, where they produce interference fringes that can be visualized through the illustrated eyepiece.

[S 4] According to the Stokes' hypothesis, the speed of light should be increased or decreased when "dragged" along by the water through the aether frame, dependent upon the direction.

The interference pattern between the two beams when the light is recombined at the observer depends upon the transit times over the two paths.

The Fizeau experiment forced physicists to accept the empirical validity of an Fresnel's model, that a medium moving through the stationary aether drags light propagating through it with only a fraction of the medium's speed, with a dragging coefficient f related to the index of refraction: Although Fresnel's hypothesis was empirically successful in explaining Fizeau's results, many experts in the field, including Fizeau himself, found Fresnel's hypothesis partial aether-dragging unsatisfactory.

[S 4] In 1870 Wilhelm Veltmann demonstrated that Fresnel's formula worked for different frequencies (colors) of light.

However, if Fresnel's dragging coefficient is applied to the water in the aether frame, the travel time difference (to first order in v/c) vanishes.

Upon turning the apparatus table 180 degrees, altering the direction of a hypothetical aether wind, Hoek obtained a null result, confirming Fresnel's dragging coefficient.

[S 5][S 1]: 111 In the particular version of the experiment shown here, Hoek used a prism P to disperse light from a slit into a spectrum which passed through a collimator C before entering the apparatus.

With the apparatus oriented parallel to the hypothetical aether wind, Hoek expected the light in one circuit to be retarded 7/600 mm with respect to the other.

[P 3][S 5] Éleuthère Mascart (1872) demonstrated a result for polarized light traveling through a birefringent medium gives different velocities in accordance with Fresnel's empirical formula.

Michelson redesigned Fizeau's apparatus with larger diameter tubes and a large reservoir providing three minutes of steady water flow.

His common-path interferometer design provided automatic compensation of path length, so that white light fringes were visible at once as soon as the optical elements were aligned.

[S 8] This offered extremely stable fringes that were, to first order, completely insensitive to any movement of its optical components.

[P 6] Using a scaled-up version of Michelson's apparatus connected directly to Amsterdam's main water conduit, Zeeman was able to perform extended measurements using monochromatic light ranging from violet (4358 Å) through red (6870 Å) to confirm Lorentz's modified coefficient.

[S 10] Since then, many experiments have been conducted measuring such dragging coefficients in a diversity of materials of differing refractive index, often in combination with the Sagnac effect.

[P 12][P 13][P 14] Also a transverse dragging effect was observed, i.e. when the medium is moving at right angles to the direction of the incident light.

He succeeded in deriving Fresnel's dragging coefficient as the result of an interaction between the moving water with an undragged aether.

These are now called the Lorentz transformations in his honor, and are identical in form to the equations that Einstein was later to derive from first principles.

Unlike Einstein's equations, however, Lorentz's transformations were strictly ad hoc, their only justification being that they seemed to work.

[S 12][S 13]: 27–30 Einstein showed how Lorentz's equations could be derived as the logical outcome of a set of two simple starting postulates.

In addition Einstein recognized that the stationary aether concept has no place in special relativity, and that the Lorentz transformation concerns the nature of space and time.

"They were enough," he said.Max von Laue (1907) demonstrated[P 16] that the Fresnel drag coefficient can be explained as a natural consequence of the relativistic formula for addition of velocities.