Tests of special relativity

The strength of the theory lies in its unique ability to correctly predict to high precision the outcome of an extremely diverse range of experiments.

Beginning with the work of François Arago (1810), a series of optical experiments had been conducted, which should have given a positive result for magnitudes of first order in

In general, Hendrik Lorentz (1892, 1895) introduced several new auxiliary variables for moving observers, demonstrating why all first-order optical and electrostatic experiments have produced null results.

[1] The stationary aether theory, however, would give positive results when the experiments are precise enough to measure magnitudes of second order in

In addition, the Experiments of Rayleigh and Brace intended to measure some consequences of length contraction in the laboratory frame, for example the assumption that it would lead to birefringence.

(The Trouton–Rankine experiment conducted in 1908 also gave a negative result when measuring the influence of length contraction on an electromagnetic coil.

Henri Poincaré declared in 1905 that the impossibility of demonstrating absolute motion (principle of relativity) is apparently a law of nature.

Lodge expressed the paradoxical situation in which physicists found themselves as follows: "...at no practicable speed does ... matter [have] any appreciable viscous grip upon the ether.

Atoms must be able to throw it into vibration, if they are oscillating or revolving at sufficient speed; otherwise they would not emit light or any kind of radiation; but in no case do they appear to drag it along, or to meet with resistance in any uniform motion through it.

Besides the derivation of the Lorentz transformation, the combination of these experiments is also important because they can be interpreted in different ways when viewed individually.

For example, isotropy experiments such as Michelson-Morley can be seen as a simple consequence of the relativity principle, according to which any inertially moving observer can consider himself as at rest.

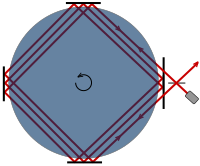

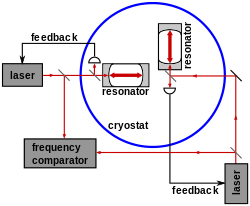

Modern variants of Michelson-Morley and Kennedy–Thorndike experiments have been conducted in order to test the isotropy of the speed of light.

Laser, maser and optical resonators are used, reducing the possibility of any anisotropy of the speed of light to the 10−17 level.

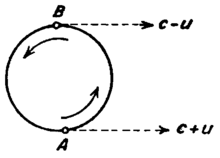

Emission theories, according to which the speed of light depends on the velocity of the source, can conceivably explain the negative outcome of aether drift experiments.

In addition, the de Sitter double star experiment (1913) was repeated by Brecher (1977) under consideration of the extinction theorem, ruling out a source dependence as well.

They are experimentally equivalent to special relativity because all of these models include effects like time dilation of moving clocks, that compensate any measurable anisotropy.

However, of all models having isotropic two-way speed, only special relativity is acceptable for the overwhelming majority of physicists since all other synchronizations are much more complicated, and those other models (such as Lorentz ether theory) are based on extreme and implausible assumptions concerning some dynamical effects, which are aimed at hiding the "preferred frame" from observation.

They are not restricted to the photon sector as Michelson-Morley but directly determine any anisotropy of mass, energy, or space by measuring the ground state of nuclei.

In modern Ives-Stilwell experiments in heavy ion storage rings using saturated spectroscopy, the maximum measured deviation of time dilation from the relativistic prediction has been limited to ≤ 10−8.

Direct confirmation of length contraction is hard to achieve in practice since the dimensions of the observed particles are vanishingly small.

However, there are indirect confirmations; for example, the behavior of colliding heavy ions can be explained if their increased density due to Lorentz contraction is considered.

Contraction also leads to an increase of the intensity of the Coulomb field perpendicular to the direction of motion, whose effects already have been observed.

Starting with 1901, a series of measurements was conducted aimed at demonstrating the velocity dependence of the mass of electrons.

The results actually showed such a dependency but the precision necessary to distinguish between competing theories was disputed for a long time.

Today, special relativity's predictions are routinely confirmed in particle accelerators such as the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider.

For example, the increase of relativistic momentum and energy is not only precisely measured but also necessary to understand the behavior of cyclotrons and synchrotrons etc., by which particles are accelerated near to the speed of light.

Several test theories have been developed to assess a possible positive outcome in Lorentz violation experiments by adding certain parameters to the standard equations.

Because "local Lorentz invariance" (LLI) also holds in freely falling frames, experiments concerning the weak Equivalence principle belong to this class of tests as well.