Scandinavian Mountains

To the north they form the border between Norway and Sweden, reaching 2,000 metres (6,600 ft) high at the Arctic Circle.

The mountain range just touches northwesternmost Finland but are scarcely more than hills at their northernmost extension at the North Cape (Nordkapp).

The Scandinavian montane birch forest and grasslands terrestrial ecoregion is closely associated with the mountain range.

In Swedish, the mountain range is called Skandinaviska fjällkedjan, Skanderna (encyclopedic and professional usage), Fjällen ('the Fells', common in colloquial speech) or Kölen ('the Keel').

In Norwegian, it is called Den skandinaviske fjellkjede, Fjellet, Skandesfjellene, Kjølen ('the Keel') or Nordryggen ('the North Ridge', name coined in 2013).

The names Kölen and Kjølen are often preferentially used for the northern part, where the mountains form a narrow range near the border region of Norway and Sweden.

In South Norway, there is a broad scatter of mountain regions with individual names, such as Dovrefjell, Hardangervidda, Jotunheimen, and Rondane.

[10] This part of the mountain chain is also broader and contains a series of plateaux and gently undulating surfaces[8][11] that hosts scattered inselbergs.

[12] In south-western Norway, the plateaux and gently undulating surfaces are strongly dissected by fjords and valleys.

While lower than the Scandinavian Mountains proper, the förfjäll's pronounced relief, its large number of plateaux, and its coherent valley system distinguish it from so-called undulating hilly terrain (Swedish: bergkullsterräng) and plains with residual hills (Swedish: bergkullslätt) found further east.

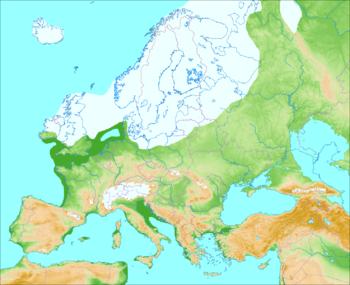

[17] The climate of the Nordic countries is maritime along the coast of Norway, and much more continental in Sweden in the rain shadow of the Scandinavian Mountains.

The combination of a northerly location and moisture from the North Atlantic Ocean has caused the formation of many ice fields and glaciers.

[22][23] The Caledonian Mountains began a post-orogenic collapse in the Devonian, implying tectonic extension and subsidence.

[32] The various episodes of uplift of the Scandinavian Mountains were similar in orientation and tilted land surfaces to the east while allowing rivers to incise the landscape.

Folding could have been caused by horizontal compression acting on a thin to thick crust transition zone (as are all passive margins).

[25] One hypothesis states that the early uplift of the Scandinavian Mountains could be indebted to changes in the density of the lithosphere and asthenosphere caused by the Iceland plume when Greenland and Scandinavia rifted apart about 53 million years ago.

[13] Karst systems, with their characteristic caves and sinkholes, occur at various places in the Scandinavian Mountains, but are more common in the northern parts.

[13] Much of the mountain range is mantled by deposits of glacial origin including till blankets, moraines, drumlins and glaciofluvial material in the form of outwash plains and eskers.

These two centres were for a time linked, so that the linkage constituted a major drainage barrier that formed various large ephemeral ice-dammed lakes.

About 10 ka BP, the linkage had disappeared and so did the southern centre of the ice sheet a thousand years later.

The northern centre remained a few hundred years more, and by 9,7 ka BP the eastern Sarek Mountains hosted the last remnant of the Fennoscandian Ice Sheet.

[44] Of the 10 highest mountain peaks in Scandinavia (prominence greater than 30 m or 98 ft), six are situated in Oppland, Norway.