Flagellum

: flagella) (Latin for 'whip' or 'scourge') is a hair-like appendage that protrudes from certain plant and animal sperm cells, from fungal spores (zoospores), and from a wide range of microorganisms to provide motility.

[6] Across the three domains of Bacteria, Archaea, and Eukaryota, the flagellum has a different structure, protein composition, and mechanism of propulsion but shares the same function of providing motility.

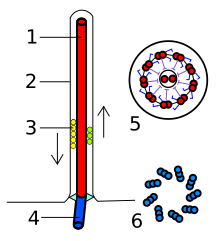

It is helical and has a sharp bend just outside the outer membrane; this "hook" allows the axis of the helix to point directly away from the cell.

A shaft runs between the hook and the basal body, passing through protein rings in the cell's membrane that act as bearings.

[21][22] The flagellar filament is the long, helical screw that propels the bacterium when rotated by the motor, through the hook.

[23] The basal body has several traits in common with some types of secretory pores, such as the hollow, rod-like "plug" in their centers extending out through the plasma membrane.

The atomic structure of both bacterial flagella as well as the TTSS injectisome have been elucidated in great detail, especially with the development of cryo-electron microscopy.

The engine is powered by proton-motive force, i.e., by the flow of protons (hydrogen ions) across the bacterial cell membrane due to a concentration gradient set up by the cell's metabolism (Vibrio species have two kinds of flagella, lateral and polar, and some are driven by a sodium ion pump rather than a proton pump[26]).

[29] The production and rotation of a flagellum can take up to 10% of an Escherichia coli cell's energy budget and has been described as an "energy-guzzling machine".

At such a speed, a bacterium would take about 245 days to cover 1 km; although that may seem slow, the perspective changes when the concept of scale is introduced.

In comparison to macroscopic life forms, it is very fast indeed when expressed in terms of number of body lengths per second.

[32] Through use of their flagella, bacteria are able to move rapidly towards attractants and away from repellents, by means of a biased random walk, with runs and tumbles brought about by rotating its flagellum counterclockwise and clockwise, respectively.

[34] During flagellar assembly, components of the flagellum pass through the hollow cores of the basal body and the nascent filament.

[35] In vitro, flagellar filaments assemble spontaneously in a solution containing purified flagellin as the sole protein.

However, the flagellar system appears to involve more proteins overall, including various regulators and chaperones, hence it has been argued that flagella evolved from a T3SS.

[37] Furthermore, several processes have been identified as playing important roles in flagellar evolution, including self-assembly of simple repeating subunits, gene duplication with subsequent divergence, recruitment of elements from other systems ('molecular bricolage') and recombination.

Spirochetes, in contrast, have flagella called endoflagella arising from opposite poles of the cell, and are located within the periplasmic space as shown by breaking the outer-membrane and also by electron cryotomography microscopy.

[51] The rotation of the filaments relative to the cell body causes the entire bacterium to move forward in a corkscrew-like motion, even through material viscous enough to prevent the passage of normally flagellated bacteria.

This may cause the cell to stop its forward motion and instead start twitching in place, referred to as tumbling.

Tumbling results in a stochastic reorientation of the cell, causing it to change the direction of its forward swimming.

In the model describing chemotaxis ("movement on purpose") the clockwise rotation of a flagellum is suppressed by chemical compounds favorable to the cell (e.g. food).

The radial spoke is thought to be involved in the regulation of flagellar motion, although its exact function and method of action are not yet understood.

These include: These differences support the theory that the bacterial flagella and archaella are a classic case of biological analogy, or convergent evolution, rather than homology.

Nine interconnected props attach the kinetosome to the plasmalemma, and a terminal plate is present in the transitional zone.

An inner ring-like structure attached to the tubules of the flagellar doublets within the transitional zone has been observed in transverse section.