Josephus

Flavius Josephus[a] (/dʒoʊˈsiːfəs/;[9] Ancient Greek: Ἰώσηπος, Iṓsēpos; c. AD 37 – c. 100) or Yosef ben Mattityahu (Hebrew: יוֹסֵף בֵּן מַתִּתְיָהוּ) was a Roman–Jewish historian and military leader.

Best known for writing The Jewish War, he was born in Jerusalem—then part of the Roman province of Judea—to a father of priestly descent and a mother who claimed royal ancestry.

Josephus claimed the Jewish messianic prophecies that initiated the First Jewish–Roman War made reference to Vespasian becoming Roman emperor.

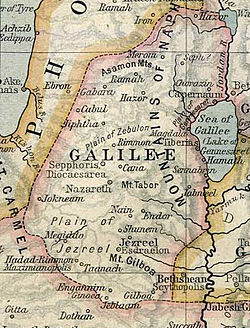

[20] His arrival in Galilee, however, was fraught with internal division: the inhabitants of Sepphoris and Tiberias opted to maintain peace with the Romans; the people of Sepphoris enlisted the help of the Roman army to protect their city,[21] while the people of Tiberias appealed to King Agrippa's forces to protect them from the insurgents.

[26] Meanwhile, Josephus fortified several towns and villages in Lower Galilee, among which were Tiberias, Bersabe, Selamin, Japha, and Tarichaea, in anticipation of a Roman onslaught.

Josephus first engaged the Roman army at a village called Garis, where he launched an attack against Sepphoris a second time, before being repulsed.

After the Jewish garrison of Yodfat fell under siege, the Romans invaded, killing thousands; the survivors committed suicide.

[31] According to his account, he acted as a negotiator with the defenders during the siege of Jerusalem in 70 AD, during which time his parents were held as hostages by Simon bar Giora.

[32] While being confined at Yodfat (Jotapata), Josephus claimed to have experienced a divine revelation that later led to his speech predicting Vespasian would become emperor.

The works of Josephus provide information about the First Jewish–Roman War and also represent literary source material for understanding the context of the Dead Sea Scrolls and late Temple Judaism.

As a Jewish scholar, as an officer of Galilee, as a military man, and a person of great experience in everything belonging to his own nation, he attained to that remarkable familiarity with his country in every part, which his antiquarian researches so abundantly evince.

[44] His writings provide a significant, extra-Biblical account of the post-Exilic period of the Maccabees, the Hasmonean dynasty, and the rise of Herod the Great.

[46] It was above aqueducts and pools, at a flattened desert site, halfway up the hill to the Herodium, 12 km south of Jerusalem—as described in Josephus's writings.

[48] Josephus's writings provide the first-known source for many stories considered as Biblical history, despite not being found in the Bible or related material.

These include Ishmael as the founder of the Arabs,[49] the connection of "Semites", "Hamites" and "Japhetites" to the classical nations of the world, and the story of the siege of Masada.

The most common motive suggested is repentance: in later life he felt so bad about the traitorous War that he needed to demonstrate … his loyalty to Jewish history, law and culture.

"[51] However, Josephus's "countless incidental remarks explaining basic Judean language, customs and laws … assume a Gentile audience.

[54] Josephus was a very popular writer with Christians in the 4th century and beyond as an independent source to the events before, during, and after the life of Jesus of Nazareth.

Improvements in printing technology (the Gutenberg Press) led to his works receiving a number of new translations into the vernacular languages of Europe, generally based on the Latin versions.

The 1544 Greek edition formed the basis of the 1732 English translation by William Whiston, which achieved enormous popularity in the English-speaking world.

[55][56] Later editions of the Greek text include that of Benedikt Niese, who made a detailed examination of all the available manuscripts, mainly from France and Spain.

Henry St. John Thackeray and successors such as Ralph Marcus used Niese's version for the Loeb Classical Library edition widely used today.

Kalman Schulman finally created a Hebrew translation of the Greek text of Josephus in 1863, although many rabbis continued to prefer the Yosippon version.

Notably, the last stand at Masada (described in The Jewish War), which past generations had deemed insane and fanatical, received a more positive reinterpretation as an inspiring call to action in this period.

"[62] His preface to Antiquities offers his opinion early on, saying, "Upon the whole, a man that will peruse this history, may principally learn from it, that all events succeed well, even to an incredible degree, and the reward of felicity is proposed by God.

In AD 78 he finished a seven-volume account in Greek known as the Jewish War (Latin Bellum Judaicum or De Bello Judaico).

He blames the Jewish War on what he calls "unrepresentative and over-zealous fanatics" among the Jews, who led the masses away from their traditional aristocratic leaders (like himself), with disastrous results.

The next work by Josephus is his 21-volume Antiquities of the Jews, completed during the last year of the reign of the Emperor Flavius Domitian, around 93 or 94 AD.

Life 430) – where the author for the most part re-visits the events of the War and his tenure in Galilee as governor and commander, apparently in response to allegations made against him by Justus of Tiberias (cf.

Some anti-Judaic allegations ascribed by Josephus to the Greek writer Apion and myths accredited to Manetho are also addressed.