Friction

Friction is the force resisting the relative motion of solid surfaces, fluid layers, and material elements sliding against each other.

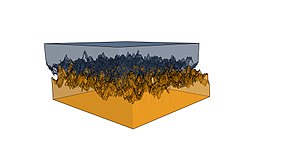

[5][6] As briefly discussed later, there are many different contributors to the retarding force in friction, ranging from asperity deformation to the generation of charges and changes in local structure.

The complexity of the interactions involved makes the calculation of friction from first principles difficult and it is often easier to use empirical methods for analysis and the development of theory.

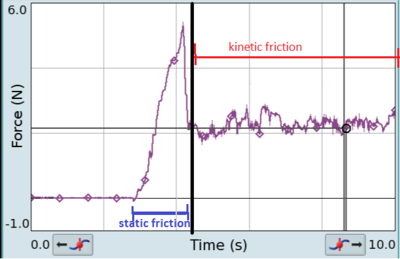

This view was further elaborated by Bernard Forest de Bélidor[23] and Leonhard Euler (1750), who derived the angle of repose of a weight on an inclined plane and first distinguished between static and kinetic friction.

[16] Coulomb further considered the influence of sliding velocity, temperature and humidity, in order to decide between the different explanations on the nature of friction that had been proposed.

John Leslie (1766–1832) noted a weakness in the views of Amontons and Coulomb: If friction arises from a weight being drawn up the inclined plane of successive asperities, then why is it not balanced through descending the opposite slope?

Leslie was equally skeptical about the role of adhesion proposed by Desaguliers, which should on the whole have the same tendency to accelerate as to retard the motion.

[16] In Leslie's view, friction should be seen as a time-dependent process of flattening, pressing down asperities, which creates new obstacles in what were cavities before.

In 1842, Julius Robert Mayer frictionally generated heat in paper pulp and measured the temperature rise.

[27] In 1845, Joule published a paper entitled The Mechanical Equivalent of Heat, in which he specified a numerical value for the amount of mechanical work required to "produce a unit of heat", based on the friction of an electric current passing through a resistor, and on the friction of a paddle wheel rotating in a vat of water.

This completed the classic empirical model of friction (static, kinetic, and fluid) commonly used today in engineering.

The friction coefficient is an empirical (experimentally measured) structural property that depends only on various aspects of the contacting materials, such as surface roughness.

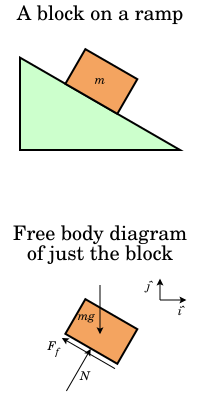

In general, process for solving any statics problem with friction is to treat contacting surfaces tentatively as immovable so that the corresponding tangential reaction force between them can be calculated.

An anti-lock braking system operates on the principle of allowing a locked wheel to resume rotating so that the car maintains static friction.

[57] This was reported in the journal Nature in October 2012 and involved the friction encountered by an atomic force microscope stylus when dragged across a graphene sheet in the presence of graphene-adsorbed oxygen.

Even its most simple expression encapsulates the fundamental effects of sticking and sliding which are required in many applied cases, although specific algorithms have to be designed in order to efficiently numerically integrate mechanical systems with Coulomb friction and bilateral or unilateral contact.

[67] In particular, friction-related dynamical instabilities are thought to be responsible for brake squeal and the 'song' of a glass harp,[68][69] phenomena which involve stick and slip, modelled as a drop of friction coefficient with velocity.

A connection between dry friction and flutter instability in a simple mechanical system has been discovered,[71] watch the movie Archived 2015-01-10 at the Wayback Machine for more details.

Adequate lubrication allows smooth continuous operation of equipment, with only mild wear, and without excessive stresses or seizures at bearings.

When lubrication breaks down, metal or other components can rub destructively over each other, causing heat and possibly damage or failure.

There are two ways to decrease skin friction: the first is to shape the moving body so that smooth flow is possible, like an airfoil.

Internal friction is the force resisting motion between the elements making up a solid material while it undergoes deformation.

As a consequence of light pressure, Einstein[73] in 1909 predicted the existence of "radiation friction" which would oppose the movement of matter.

[75] One of the most common examples of rolling resistance is the movement of motor vehicle tires on a road, a process which generates heat and sound as by-products.

[76] Any wheel equipped with a brake is capable of generating a large retarding force, usually for the purpose of slowing and stopping a vehicle or piece of rotating machinery.

Mountain climbers and sailing crews demonstrate a standard knowledge of belt friction when accomplishing basic tasks.

Superlubricity, a recently discovered effect, has been observed in graphite: it is the substantial decrease of friction between two sliding objects, approaching zero levels.

Since heat quickly dissipates, many early philosophers, including Aristotle, wrongly concluded that moving objects come to rest spontaneously.

Excessive erosion or wear of mating sliding surfaces occurs when work due to frictional forces rise to unacceptable levels.

Harder corrosion particles caught between mating surfaces in relative motion (fretting) exacerbates wear of frictional forces.