Foam

[2]: 4 The word derives from the medieval German and otherwise obsolete veim, in reference to the "frothy head forming in the glass once the beer has been freshly poured" (cf.

[citation needed] In closed-cell foam, the gas forms discrete pockets, each completely surrounded by the solid material.

A bath sponge is an example of an open-cell foam:[not verified in body] water easily flows through the entire structure, displacing the air.

[not verified in body] In general, gas is present, so it divides into gas bubbles of different sizes (i.e., the material is polydisperse[not verified in body])—separated by liquid regions that may form films, thinner and thinner when the liquid phase drains out of the system films.

[5][page needed] When the principal scale is small, i.e., for a very fine foam, this dispersed medium can be considered a type of colloid.

[citation needed] At larger sizes, the study of idealized foams is closely linked to the mathematical problems of minimal surfaces and three-dimensional tessellations, also called honeycombs.

[citation needed] The Weaire–Phelan structure is reported in one primary philosophical source to be the best possible (optimal) unit cell of a perfectly ordered foam,[6][better source needed] while Plateau's laws describe how soap-films form structures in foams.

[citation needed] Most of the time this interface is stabilized by a layer of amphiphilic structure, often made of surfactants, particles (Pickering emulsion), or more complex associations.

One of the ways foam is created is through dispersion, where a large amount of gas is mixed with a liquid.

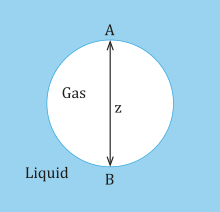

A more specific method of dispersion involves injecting a gas through a hole in a solid into a liquid.

If this process is completed very slowly, then one bubble can be emitted from the orifice at a time as shown in the picture below.

is substituted in to the equation above, separation occurs at the moment when Examining this phenomenon from a capillarity viewpoint for a bubble that is being formed very slowly, it can be assumed that the pressure

[7] The stabilization of foam is caused by van der Waals forces between the molecules in the foam, electrical double layers created by dipolar surfactants, and the Marangoni effect, which acts as a restoring force to the lamellae.

For laplace pressure of a curved gas liquid interface, the two principal radii of curvature at a point are R1 and R2.

In addition, as z increases, this causes the difference in RA and RB too, which means the bubble deviates more from its shape the larger it grows.

First, gravitation causes drainage of liquid to the foam base, which Rybczynski and Hadamar include in their theory; however, foam also destabilizes due to osmotic pressure causes drainage from the lamellas to the Plateau borders due to internal concentration differences in the foam, and Laplace pressure causes diffusion of gas from small to large bubbles due to pressure difference.

In addition, films can break under disjoining pressure, These effects can lead to rearrangement of the foam structure at scales larger than the bubbles, which may be individual (T1 process) or collective (even of the "avalanche" type).

They often have lower nodal connectivity[jargon] as compared to other cellular structures like honeycombs and truss lattices, and thus, their failure mechanism is dominated by bending of members.

[11][12] The strength of foams can be impacted by the density, the material used, and the arrangement of the cellular structure (open vs closed and pore isotropy).

The stiffness of the material can be calculated from the linear elastic regime [14] where the modulus for open celled foams can be defined by the equation:

Another important property which can be deduced from the stress strain curve is the energy that the foam is able to absorb.

This equation is derived from assuming an idealized foam with engineering approximations from experimental results.

Most energy absorption occurs at the plateau stress region after the steep linear elastic regime.

[citation needed] The isotropy of the cellular structure and the absorption of fluids can also have an impact on the mechanical properties of a foam.

At high enough cell resolutions, any type can be treated as continuous or "continuum" materials and are referred to as cellular solids,[23] with predictable mechanical properties.

Wheat gluten/TEOS bio-foams have been produced, showing similar insulator properties as for those foams obtained from oil-based resources.

However, closed-cell foams are also, in general more dense, require more material, and as a consequence are more expensive to produce.

The earliest known engineering use of cellular solids is with wood, which in its dry form is a closed-cell foam composed of lignin, cellulose, and air.

An example of the use of azodicarbonamide[26] as a blowing agent is found in the manufacture of vinyl (PVC) and EVA-PE foams, where it plays a role in the formation of air bubbles by breaking down into gas at high temperature.

Examples of items produced using this process include arm rests, baby seats, shoe soles, and mattresses.