Physics

Physics is the scientific study of matter, its fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force.

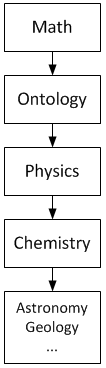

New ideas in physics often explain the fundamental mechanisms studied by other sciences[2] and suggest new avenues of research in these and other academic disciplines such as mathematics and philosophy.

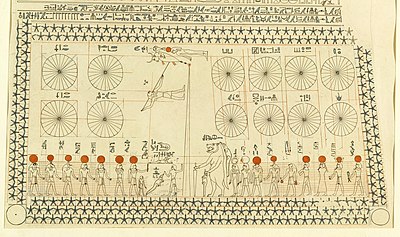

Early civilizations dating before 3000 BCE, such as the Sumerians, ancient Egyptians, and the Indus Valley Civilisation, had a predictive knowledge and a basic awareness of the motions of the Sun, Moon, and stars.

[9] Egyptian astronomers left monuments showing knowledge of the constellations and the motions of the celestial bodies,[10] while Greek poet Homer wrote of various celestial objects in his Iliad and Odyssey; later Greek astronomers provided names, which are still used today, for most constellations visible from the Northern Hemisphere.

[14] During the classical period in Greece (6th, 5th and 4th centuries BCE) and in Hellenistic times, natural philosophy developed along many lines of inquiry.

Aristotle (Greek: Ἀριστοτέλης, Aristotélēs) (384–322 BCE), a student of Plato, wrote on many subjects, including a substantial treatise on "Physics" – in the 4th century BC.

His approach mixed some limited observation with logical deductive arguments, but did not rely on experimental verification of deduced statements.

[19] In the sixth century, John Philoponus challenged the dominant Aristotelian approach to science although much of his work was focused on Christian theology.

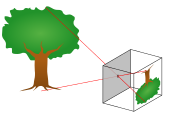

The most notable work was The Book of Optics (also known as Kitāb al-Manāẓir), written by Ibn al-Haytham, in which he presented the alternative to the ancient Greek idea about vision.

[22] His discussed his experiments with camera obscura, showing that light moved in a straight line; he encouraged readers to reproduce his experiments making him one of the originators of the scientific method[23][24] Physics became a separate science when early modern Europeans used experimental and quantitative methods to discover what are now considered to be the laws of physics.

[25][page needed] Major developments in this period include the replacement of the geocentric model of the Solar System with the heliocentric Copernican model, the laws governing the motion of planetary bodies (determined by Kepler between 1609 and 1619), Galileo's pioneering work on telescopes and observational astronomy in the 16th and 17th centuries, and Isaac Newton's discovery and unification of the laws of motion and universal gravitation (that would come to bear his name).

[28] The discovery of laws in thermodynamics, chemistry, and electromagnetics resulted from research efforts during the Industrial Revolution as energy needs increased.

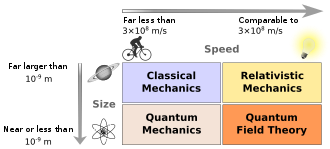

This discrepancy was corrected by Einstein's theory of special relativity, which replaced classical mechanics for fast-moving bodies and allowed for a constant speed of light.

[31] Black-body radiation provided another problem for classical physics, which was corrected when Planck proposed that the excitation of material oscillators is possible only in discrete steps proportional to their frequency.

[30]: 6 Classical physics includes the traditional branches and topics that were recognized and well-developed before the beginning of the 20th century—classical mechanics, thermodynamics, and electromagnetism.

[46] Physics covers a wide range of phenomena, from elementary particles (such as quarks, neutrinos, and electrons) to the largest superclusters of galaxies.

But even before the Chinese discovered magnetism, the ancient Greeks knew of other objects such as amber, that when rubbed with fur would cause a similar invisible attraction between the two.

The Large Hadron Collider has already found the Higgs boson, but future research aims to prove or disprove the supersymmetry, which extends the Standard Model of particle physics.

[53] Although much progress has been made in high-energy, quantum, and astronomical physics, many everyday phenomena involving complexity,[54] chaos,[55] or turbulence[56] are still poorly understood.

Complex physics has become part of increasingly interdisciplinary research, as exemplified by the study of turbulence in aerodynamics and the observation of pattern formation in biological systems.

In the 1932 Annual Review of Fluid Mechanics, Horace Lamb said:[58] I am an old man now, and when I die and go to heaven there are two matters on which I hope for enlightenment.

[65] The model accounts for the 12 known particles of matter (quarks and leptons) that interact via the strong, weak, and electromagnetic fundamental forces.

[51] The most familiar examples of condensed phases are solids and liquids, which arise from the bonding by way of the electromagnetic force between atoms.

Perturbations and interference from the Earth's atmosphere make space-based observations necessary for infrared, ultraviolet, gamma-ray, and X-ray astronomy.

The Big Bang model rests on two theoretical pillars: Albert Einstein's general relativity and the cosmological principle.

[88] Many physicists have written about the philosophical implications of their work, for instance Laplace, who championed causal determinism,[89] and Erwin Schrödinger, who wrote on quantum mechanics.

Some theorists, like Hilary Putnam and Penelope Maddy, hold that logical truths, and therefore mathematical reasoning, depend on the empirical world.

This is usually combined with the claim that the laws of logic express universal regularities found in the structural features of the world, which may explain the peculiar relation between these fields.

Fundamental physics seeks to better explain and understand phenomena in all spheres, without a specific practical application as a goal, other than the deeper insight into the phenomema themselves.

An understanding of physics makes for more realistic flight simulators, video games, and movies, and is often critical in forensic investigations.