Smith Act trials of Communist Party leaders

Progressive Era Repression and persecution Anti-war and civil rights movements Contemporary The Smith Act trials of Communist Party leaders in New York City from 1949 to 1958 were the result of US federal government prosecutions in the postwar period and during the Cold War between the Soviet Union and the United States.

Leaders of the Communist Party of the United States (CPUSA) were accused of violating the Smith Act, a statute that prohibited advocating violent overthrow of the government.

While the first trial was under way, events outside the courtroom influenced public perception of communism: the Soviet Union tested its first nuclear weapon, and communists prevailed in the Chinese Civil War.

In this period, the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) had also begun conducting investigations and hearings of writers and producers in Hollywood suspected of communist influence.

Subsequent international events served to increase the apparent danger that communism posed to Americans: the Stalinist threats in the Greek Civil War (1946–1949); the Czechoslovak coup d'état of 1948; and the 1948 blockade of Berlin.

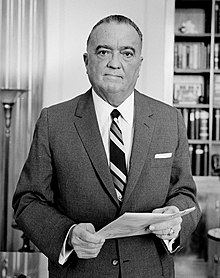

In July 1945, FBI director J. Edgar Hoover instructed his agents to begin gathering information on CPUSA members, leading to a 1,850-page report published in 1946 which outlined a case for their prosecution.

[17] John McGohey, a federal prosecutor from the Southern District of New York, was given the lead role in prosecuting the case and charged twelve leaders of the CPUSA with violations of the Smith Act.

[24][25] The trial opened on November 1, 1948, and preliminary proceedings and jury selection lasted until January 17, 1949; the defendants first appeared in court on March 7, and the case concluded on October 14, 1949.

[37] Before the trial began, supporters of the defendants decided on a campaign of letter-writing and demonstrations: the CPUSA urged its members to bombard Truman with letters requesting that the charges be dropped.

[42] The prosecution witnesses testified about the goals and policies of the CPUSA, and they interpreted the statements of pamphlets and books (including The Communist Manifesto) and works by such authors as Karl Marx and Joseph Stalin.

The ACLU was dominated by anti-communist leaders during the 1940s, and did not enthusiastically support persons indicted under the Smith Act; but it did submit an amicus brief endorsing a motion for dismissal of the charges.

[49] The defense made pre-trial motions arguing that the defendants' right to trial by a jury of their peers had been denied because, at that time, a potential grand juror had to meet a minimum property requirement, effectively eliminating the less affluent from service.

[52] The defense claimed that most of the prosecution's documentary evidence came from older texts that pre-dated the 1935 Seventh World Congress of the Comintern, after which the CPUSA rejected violence as a means of change.

[25][54] During the ten-month trial, several events occurred in America that intensified the nation's anti-communist sentiment: The Judith Coplon Soviet espionage case was in progress; former government employee Alger Hiss was tried for perjury stemming from accusations that he was a communist (a trial also held at the Foley Square courthouse); labor leader Harry Bridges was accused of perjury when he denied being a communist; and the ACLU passed an anti-communist resolution.

Three months after the trial, in January 1950, a representative of the Justice Department testified before Congress during appropriation hearings to justify an increase in funding to support Smith Act prosecutions.

[99] Their free speech arguments raised important constitutional issues: they asserted that their political advocacy was protected by the First Amendment, because the CPUSA did not advocate imminent violence, but instead merely promoted revolution as an abstract concept.

One of the major issues raised on appeal was that the defendants' political advocacy was protected by the First Amendment, because the CPUSA did not advocate imminent violence, but instead merely promoted revolution as an abstract concept.

[105][106] The Court continued to use the bad tendency test during the early twentieth century in cases such as 1919's Abrams v. United States which upheld the conviction of anti-war activists who passed out leaflets encouraging workers to impede the war effort.

Judge Hand considered the clear and present danger test, but his opinion adopted a balancing approach similar to that suggested in American Communications Association v.

The American Communist Party, of which the defendants are the controlling spirits, is a highly articulated, well contrived, far spread organization, numbering thousands of adherents, rigidly and ruthlessly disciplined, many of whom are infused with a passionate Utopian faith that is to redeem mankind....

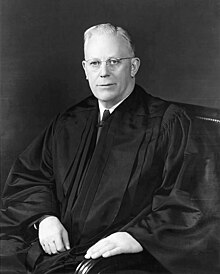

Chief Justice Fred Vinson's opinion stated that the First Amendment does not require that the government must wait "until the putsch is about to be executed, the plans have been laid and the signal is awaited" before it interrupts seditious plots.

The defendants claimed that Medina's statement that "as matter of law that there is sufficient danger of a substantive evil that the Congress has a right to prevent to justify the application of the statute under the First Amendment of the Constitution" was erroneous, but Vinson concluded that the instructions were an appropriate interpretation of the Smith Act.

There is hope, however, that, in calmer times, when present pressures, passions and fears subside, this or some later Court will restore the First Amendment liberties to the high preferred place where they belong in a free society.

I have reluctantly concluded that neither is blameless, that there is fault on each side, that we have here the spectacle of the bench and the bar using the courtroom for an unseemly demonstration of garrulous discussion and of ill will and hot tempers.

[128] The attorneys raised a variety of issues on appeal, including the purported misconduct of the judge, and the claim that they were deprived of due process because there was no hearing to evaluate the merits of the contempt charge.

[91] Jackson's opinion stated that "summary punishment always, and rightly, is regarded with disfavor, and, if imposed in passion or pettiness, brings discredit to a court as certainly as the conduct it penalizes.

[4] In a unanimous decision, the court reversed the conviction because the evidence presented at trial was not sufficient to demonstrate that the Party was advocating action (as opposed to mere doctrine) of forcible overthrow of the government.

[155] On behalf of the majority, Justice Harlan wrote:[156] The evidence was insufficient to prove that the Communist Party presently advocated forcible overthrow of the Government not as an abstract doctrine, but by the use of language reasonably and ordinarily calculated to incite persons to action, immediately or in the future....

In order to support a conviction under the membership clause of the Smith Act, there must be some substantial direct or circumstantial evidence of a call to violence now or in the future which is both sufficiently strong and sufficiently pervasive to lend color to the otherwise ambiguous theoretical material regarding Communist Party teaching and to justify the inference that such a call to violence may fairly be imputed to the Party as a whole, and not merely to some narrow segment of it.The decision did not rule the membership clause unconstitutional.

[179] Irving Potash moved to Poland after his release from prison, then re-entered the United States illegally in 1957, and was arrested and sentenced to two years for violating immigration laws.