Foot plough

Before the widespread use of metal farm tools from Europe, the Māori people used the kō, a version of the foot plough made entirely of wood.

Just below the crook or angle, there must be a hole wherein a straight peg must be fixed, for the workman’s right foot in order to push the instrument into the earth; while in the mean time, standing on his left foot, and holding the shaft firmly with both hands, when he has in this manner driven the head into the earth, with one bend of his body he raises the clod by the iron-headed part of the instrument, making use of the ‘heel’ or hind part of the head as a fulcrum.

[4] No other indigenous tool utilized the pressure of the foot in digging up the sod which made it different from all farming implements known elsewhere in the Americas in pre-Columbian times.

[5] Although Chakitaqlla is a relatively simple instrument, it has persisted long after more sophisticated technology was introduced into the Central Andes, and its enduring presence demonstrates that more advanced innovations do not necessarily displace primitive forms that under certain conditions may be more efficient.

[4] With the expansion of the Inca Empire, the taklla was carried north to Ecuador and south to Bolivia where early colonial writings confirmed its presence.

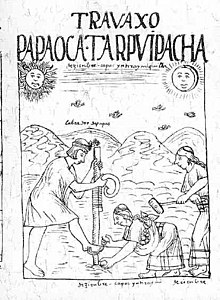

It was made of a pole about 2 metres (6 ft 7 in) long with a pointed end of wood or bronze, a handle or curvature at the top, and a foot rest lashed near the bottom.

[10] The Inca Emperor and accompanying provincial lords used foot ploughs in the "opening of the earth" ceremony at the beginning of the agricultural cycle.