Foraging

The payoff for many of these models is the amount of energy an animal receives per unit time, more specifically, the highest ratio of energetic gain to cost while foraging.

[2] Foraging theory predicts that the decisions that maximize energy per unit time and thus deliver the highest payoff will be selected for and persist.

Their goal was to quantify and formalize a set of models to test their null hypothesis that animals forage randomly.

[3] Since an animal's environment is constantly changing, the ability to adjust foraging behavior is essential for maximization of fitness.

One measure of learning is 'foraging innovation'—an animal consuming new food, or using a new foraging technique in response to their dynamic living environment.

[5] A higher ability to innovate has been linked to larger forebrain sizes in North American and British Isle birds according to Lefebvre et al.

[6] In this study, bird orders that contained individuals with larger forebrain sizes displayed a higher amount of foraging innovation.

Examples of innovations recorded in birds include following tractors and eating frogs or other insects killed by it and using swaying trees to catch their prey.

[7] This type of learning has been documented in the foraging behaviors of individuals of the stingless bee species Trigona fulviventris.

Studies using quantitative trait loci (QTL) mapping have associated the following loci with the matched functions; Pln-1 and Pln-4 with onset of foraging age, Pln-1 and 2 with the size of the pollen loads collected by workers, and Pln-2 and pln-3 were shown to influence the sugar concentration of the nectar collected.

In a study using fruit fly larvae (Drosophila melanogaster), there were two types of foraging strategies: rovers and sitters.

[13] Interactions with the environment significantly influence foraging behavior by dictating the availability of resources, the competition among others, the presence of predators, and the complexity of the landscape.

These factors can affect the strategies animals use to find food, the risks they're willing to take, and the efficiency of their foraging patterns.

[15] For instance, Blepharida rhois differ in their behavior based on the food resources available in their environment.

For example, Bolas spiders attack their prey by luring them with a scent identical to the female moth's sex pheromones.

An example of an exclusive solitary forager is the South American species of the harvester ant, Pogonomyrmex vermiculatus.

They remain motionless for long durations as they wait on the prey to pass by, therefore initiating the ambusher to attack.

Optimal foraging theory (OFT) was first proposed in 1966, in two papers published independently, by Robert MacArthur and Eric Pianka,[25] and by J. Merritt Emlen.

Departures from optimality often help to identify constraints either in the animal's behavioral or cognitive repertoire, or in the environment, that had not previously been suspected.

It is likely that an individual will settle for a trade off between maximizing the intake rate while eating and minimising the search interval between prey.

[27] The biological behavior also inspired the development of Artificial Intelligence algorithms that try to follow the main concepts of group foraging by autonomous agents.

The first situation is frequently thought of and occurs when foraging in a group is beneficial and brings greater rewards known as an aggregation economy.

These workers can utilize many different methods of communicating while foraging in a group, such as guiding flights, scent paths, and "jostling runs", as seen in the eusocial bee Melipona scutellaris.

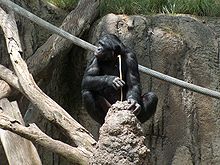

The chimps have also been observed implying rules with their foraging, where there is a benefit to becoming involved through allowing successful hunters first access to their kills.

They make decisions that reflect a balance between obtaining food, defending their territory and protecting their young.

They are not behaving optimally with respect to foraging because they have to defend their territory and protect young so they hunt in small groups to reduce the risk of being caught alone.

[37] 'Foraging arenas' are the areas in which a juvenile fish can forage closer to their home while also providing an easier escape from potential predators.

This theory predicts that feeding activity should be dependent upon the density of juvenile fishes, and the risk of predation within the area.