Foreign policy of the Russian Empire

Russia played a major role in the eventual defeat of Napoleon and in setting conservative terms for the restoration of aristocratic Europe during the period of 1815 to 1848 as the Holy Alliance.

For three centuries, from the days of Ivan the Terrible (ruled 1547 to 1584), Russia expanded in all directions at a rate of 18,000 square miles per year, becoming by far the largest power in terms of contiguous land area.

Russia expanded influence in East Asia during this time as did other Western powers and Japan, joining to suppress the Boxer Rebellion, acquiring concessions in China and invading Manchuria.

There resulted two revolutions in 1917 which destroyed the Russian Empire and led to independence for the Baltic states, Finland, Poland and (briefly) Ukraine and a host of smaller nation-states such as Georgia.

After sharp fighting in the Russian Civil War of 1917–1922 with international involvement, a new regime of Communism under Lenin secured control and established the Soviet Union (USSR) in 1922.

Although some Russian settlers were sent into Kazakhstan, generally leading local elites were left in power as long as it was clear that Russia controlled foreign and military policies.

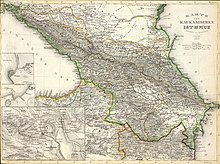

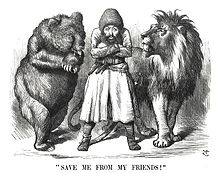

[3] The mainstream of expansion finally reached Afghanistan in the middle of the 19th century, leading to the Great Game with repeated wars against the Afghan tribes, and increasingly involved threats and counterthreats with the British, who were determined to protect their large holdings on the Indian subcontinent.

In these wars superior Russian forces often outnumbered the Swedish, which however often stood their ground in battles such as those of Narva (1700) and Svensksund (1790) due to Sweden's capable military organisation.

From the 1720s Peter invited British engineers to Saint Petersburg, leading to the establishment of a small but commercially influential Anglo-Russian expatriate merchant community from 1730 to 1921.

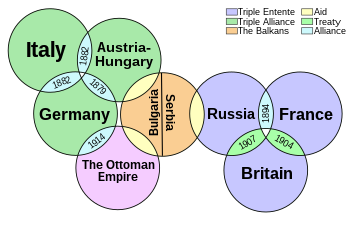

However, Britain became alarmed when Russia threatened Afghanistan, with the implicit threat to India, and decades of diplomatic maneuvering finally ended with an Anglo-Russian Entente in 1907.

At last the Crimean war at the end of his reign demonstrated to the world what no one had previously realized: Russia was militarily weak, technologically backward, and administratively incompetent.

It gave West European powers the nominal duty of protecting Christians living in the Ottoman Empire, removing that role from Russia, which had been designated as such a protector in the 1774 Treaty of Kuchuk-Kainarji.

Once the forces of Aleksandr Baryatinsky had captured the legendary Chechen rebel leader Shamil in 1859, the army resumed the expansion into Central Asia that had begun under Nicholas I.

To avoid alarming Britain, which had strong interests in protecting nearby India, Russia left the Bukhoran territories directly bordering Afghanistan and Persia nominally independent.

[47] In the 1870s, Russian nationalist opinion became a serious domestic factor in its support for liberating Balkan Christians from Ottoman rule and making Bulgaria and Serbia quasi-protectorates of Russia.

From 1875 to 1877, the Balkan crisis escalated with the rebellion in Bosnia and Herzegovina, and insurrection in Bulgaria, which the Ottoman Turks suppressed with such great cruelty that Serbia, but none of the West European powers, declared war.

Russia's nationalist diplomats and generals persuaded Alexander II to force the Ottomans to sign the Treaty of San Stefano in March 1878, creating an enlarged, independent Bulgaria that stretched into the southwestern Balkans.

Russian nationalists were furious with Austria-Hungary and Germany for failing to back Russia, but the tsar accepted a revived and strengthened League of the Three Emperors as well as Austro-Hungarian hegemony in the western Balkans.

Russia desired warm-water ports on the Indian Ocean while Britain wanted to prevent Russian troops from gaining a potential invasion route to India.

However Russia's foreign minister Nikolay Girs and its ambassador to London Baron de Staal set up an agreement in 1887 which established a buffer zone in Central Asia.

[61] Diplomat Nikolay Girs, scion of a rich and powerful family of Scandinavian descent, served as Foreign Minister, 1882–1895, during the reign of Alexander III.

Tsar Alexander took credit for peaceful policies but according to Margaret Maxwell, historians have underrated his success in a diplomacy that featured numerous negotiated settlements, treaties and conventions.

[62] Girs was usually successful in restraining the aggressive inclinations of Tsar Alexander III, convincing him that the very survival of the czarist system depended on avoiding major wars.

With a deep insight into the tsar's moods and views, Girs typically shaped the final decisions by outmaneuvering hostile journalists, ministers, and even the czarina, as well as his own ambassadors.

Most international observers expected Russia to win easily over upstart Japan—and were astonished when Japan sank the main Russian fleet and won the war, marking the first great Asian victory over a modern European power.

Japan was worried by Russia's long march east through Siberia and central Asia, and offered to recognize Russian dominance in Manchuria in exchange for recognition of Korea as being within the Japanese sphere of influence.

While the Russian decision makers were confused, Japan worked to isolate them diplomatically, especially by signing the Anglo-Japanese Alliance in 1902, (even though it did not require Britain to enter a war.)

[67] However, there was a brief war scare in October 1905 when the Russian battle fleet headed to fight Japan mistakenly engaged a number of British fishing vessels in the North Sea.

The Anglo-Russian Convention of 1907 ended the long-standing rivalry in central Asia, and then enabled the two countries to outflank the Germans, who were threatening to connect Berlin in Baghdad by new railroad that would probably align the Turkish Empire with Great Britain.

[74][75] A relatively new factor influencing Russian policy was the growth of Pan-Slavic spirit that identified Russia's duty to all Slavic speaking peoples, especially those who are Orthodox in religion.