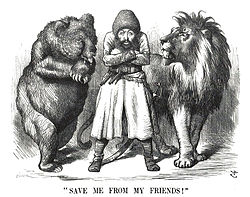

Great Game

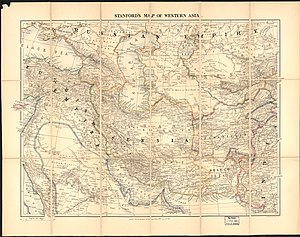

[7] Russia and Britain's 19th-century rivalry in Asia began with the planned Indian March of Paul and Russian invasions of Iran in 1804–1813 and 1826–1828, shuffling Persia into a competition between colonial powers.

He wrote to the Ataman of the Don Cossacks Troops, Cavalry General Vasily Petrovich Orlov, directing him to march to Orenburg, conquer the Central Asian Khanates, and from there invade India.

[23] The British public learned about the incident years later, but it firmly imprinted on the popular consciousness, contributing to feelings of mutual suspicion and distrust associated with the Great Game.

In response, Britain sent its own diplomatic missions in 1808, with military advisers, to Persia and Afghanistan under the capable Mountstuart Elphinstone, averting the possible French and Russian threat to India.

Fath-Ali then lent a promise to Napoleon in 1807 to theoretically invade British India in exchange for French military assistance (Gardane's mission) which fell through despite the Treaty of Finckenstein.

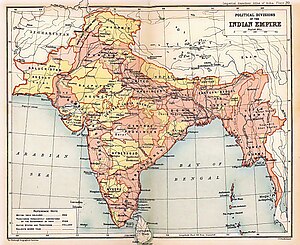

Britain believed that it was the world's first free society and the most industrially advanced country, and therefore that it had a duty to use its iron, steam power, and cotton goods to take over Central Asia and develop it.

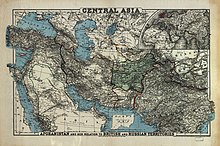

[3] Historian Alexandre Andreyev argued that the rapid advance of the Russian Empire in Central Asia, while mainly serving to extend the southern frontier, was aimed to keep British eyes off of the January uprising in Poland.

In 1831, Captain Alexander Burnes and Colonel Henry Pottinger's surveys of the Indus river would prepare the way for a future assault on the Sind to clear a path towards Central Asia.

[48] Dost Mohammad is reported to have said:I have been struck by the magnitude of your resources, your ships, your arsenals, but what I cannot understand is why the rulers of so vast and flourishing an empire should have gone across the Indus to deprive me of my poor and barren country.

In 1864, a circular was sent to the consular officers abroad by Gorchakov, the Russian Chancellor, patiently explaining the reasons for expansion centering on the doctrines of necessity, power and spread of civilisation.

[35] Gorchakov went to great lengths to explain that Russia's intentions were meant not to antagonize the British but to bring civilised behavior and protect the traditional trade routes through the region.

[70] In the 1880s, Przhevalsky advocated for the "forcible annexation of western China, Mongolia, and Tibet, and their colonization by Cossacks", although the plan received some pushback from Tsar Alexander III who favoured influence rather than an invasion.

Andreyev mentions that in 1893, Tsar Alexander III financed an adventurist project by a Tibetan medicine practitioner, Piotr Aleksandrovich Badmaev, which aimed to annex Mongolia, Tibet, and China to the Russian Empire.

Although not very successful, various agents were sent out to conduct espionage in Tibet in regards to British influence, investigate trade and attempted to foment rebellion in Mongolia against the Qing dynasty.

[76][77] The Russian General Staff wanted on-the-ground intelligence about reforms and activities by the Qing dynasty, as well as the military feasibility of invading Western China: a possible move in their struggle with Britain for control of inner Asia.

Tsar Nicholas II would be a staunch supporter of the Mohammad Ali Shah Qajar against the revolutionaries, in a large scale intervention that involved both regular Russian troops and the Persian Cossacks.

[96] However, Bismarck through the Three Emperors' League also aided Russia, by pressuring the Ottoman Empire to block the Bosporus from British naval access, compelling an Anglo-Russian negotiation regarding Afghanistan.

Durand reinforced the fort and accelerated the road construction to it, causing Nagar and Hunza to see this as an escalation and so they stopped mail from the British Resident in Chinese Turkmenistan through their territory.

[111] For a time, the British and Russian Empires moved together against potential German entrance into the Great Game, and against a constitutional movement in Iran that threatened to dispel the two-way sphere of influence.

[28][117] Hopkirk views "unofficial" British support for Circassian anti-Russian fighters in the Caucasus (c. 1836 – involving David Urquhart and (for example) the Vixen affair – in the context of the Great Game.

"[124][125] Authors Andrei Znamenski and Alexandre Andreyev also describe the continuation of elements of the Great Game by the Soviet Union until the 1930s, focused on secret diplomacy and espionage in Tibet and Mongolia.

[147] In the following year he wrote to Rawlinson, a member of the Council of India, "Our engagement with Russia with respect to the frontier of Afghanistan precludes us from promoting the incorporation of the Turkomans of Merv in the territories subject to the Ameer of Kabul".

Their problem could be solved if Mohammad Ali Jinnah, the leader of the Muslim League Party, would succeed in his plan to detach the northwest of India abutting Iran, Afghanistan and Sinkiang and establish a separate state there – Pakistan.

He states in the book:The report emphasized that 'Britain must retain its military connection with the subcontinent so as to ward off the Soviet Union's threat to the area', citing four reasons for the 'strategic importance of India to Britain'—India's 'value as a base from which forces could be suitably deployed within the Indian Ocean area, in the Middle East and the Far East'; it serving as 'a transit point for air and sea communications'; it being 'a large reserve of manpower of good fighting quality'; and the strategic importance of the northwest region to threaten the Soviet Union.[152]A.

[157] Malcolm Yapp proposed that some Britons had used the term "The Great Game" in the late 19th century to describe several different things in relation to its interests in Asia, but the primary concern of British authorities in India was the control of the indigenous population and not preventing a Russian invasion.

Robert Irwin summarizes the expeditions as "William Moorcroft, the horse doctor with a mission to find new stock for the cavalry in British India; Charles Metcalfe, the advocate of a forward policy on the frontier in the early 19th century; Alexander 'Bokhara' Burnes, the foolhardy political officer, who perished at the hands of an Afghan mob; Sir William Hay Macnaghten, the head of the ill-fated British Mission in Kabul (and a scholar who produced an important edition of The Arabian Nights); Nikolai Przhevalsky, the explorer who gave his name to a hard-to-spell horse; Francis Younghusband, the mystical imperialist; Aurel Stein, the manuscript hunter; Sven Hedin, the Nazi sympathiser who seems to have regarded Asian exploration as a proving ground for the superman; Nicholas Roerich, the artist and barmy quester after the fabled hidden city of Shambhala.

Blavatsky would be referenced by the poet Velimir Khlebnikov, who argued that Britain and Russia had both taken traits from the Kazan Khanate and Mongol Empire respectively, in their colonial struggle over Asia.

Scholar Anindita Banerjee argued this shows a "deconstruction" of national identities by identifying with a "religious, geographic, and ethnic other", relevant to the diversity of Central Asia and India and the frontier that existed between the British and Russian Empires.

[163] According to the scholar Andrei Znamenski, Soviet Communists of the 1920s aimed to extend their influence over Mongolia and Tibet, using the mythical Buddhist kingdom of Shambhala as a form of propaganda to further this mission, in a sort of "great Bolshevik game".

That led Roerich to formulate his "Great Plan," which envisaged the unification of millions of Asian peoples through a religious movement using the Future Buddha, or Maitreya, into a "Second Union of the East."