July Crisis

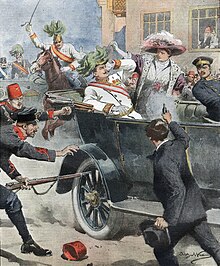

The crisis began on 28 June 1914, when Gavrilo Princip, a Bosnian Serb nationalist, assassinated Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir presumptive to the Austro-Hungarian throne, and his wife Sophie, Duchess of Hohenberg.

Following the murder, Austria-Hungary sought to inflict a military blow on Serbia, to demonstrate its own strength and to dampen Serbian support for Yugoslav nationalism, viewing it as a threat to the unity of its multi-national empire.

[11] The next day, Austro-Hungarian chargé d'affaires Count Otto von Czernin proposed to Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Sazonov that the instigators of the plot against Ferdinand needed to be investigated within Serbia, but he too was rebuffed.

[38] After meeting with Szögyény on 5 July, the German Emperor informed him that his state could "count on Germany's full support", even if "grave European complications" ensued, and that Austria-Hungary "ought to march at once" against Serbia.

[47] Austro-Hungarian policy based upon pre-existing plans to destroy Serbia involved not waiting to complete judicial inquiries to strike back immediately and not to strain its credibility in the coming weeks as it would become more and more clear that Austria-Hungary was not reacting to the assassination.

[61] On 7 July, Bethmann Hollweg told his aide and close friend Kurt Riezler that "action against Serbia can lead to a world war" and that such a "leap in the dark" was justified by the international situation.

[66][g] On 12 July, Berchtold showed Tschirschky the contents of his ultimatum containing "unacceptable demands", and promised to present it to the Serbs after the Franco-Russian summit between President Raymond Poincaré and Tsar Nicholas II was over.

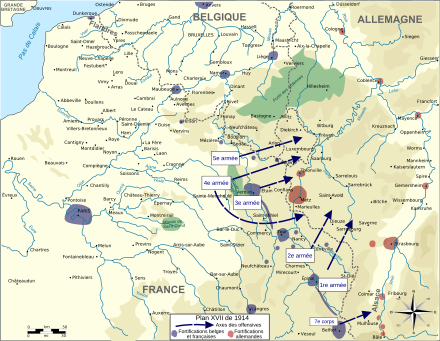

[72] Moltke argued that due to the alleged superiority of German weaponry and training, combined with the recent change in the French Army from a two-year to a three-year period of service, Germany could easily defeat both France and Russia in 1914.

[74] On 16 July, Bethmann Hollweg told Siegfried von Roedern, the State Secretary for Alsace-Lorraine, that he couldn't care less about Serbia or alleged Serbian complicity in the assassination of Franz Ferdinand.

[77] On 17 July, Berchtold complained to Prince Stolberg [de] of the German Embassy that though he thought his ultimatum would probably be rejected, he was still worried that it was possible for the Serbs to accept it, and wanted more time to re-phrase the document.

[89] Riezler's diary states Bethmann Hollweg saying on 20 July that Russia with its "growing demands and tremendous dynamic power would be impossible to repel in a few years, especially if the present European constellation continues to exist".

[82] In private, Zimmermann wrote that the German government "entirely agreed that Austria must take advantage of the favourable moment, even at the risk of further complications", but that he doubted "whether Vienna would nerve herself to act".

[102] Political scientist James Fearon argues from this episode that the Germans believed Russia were expressing greater verbal support for Serbia than they would actually provide, in order to pressure Germany and Austria-Hungary to accept some Russian demands in negotiation.

[o] An appendix listed various details from "the crime investigation undertaken at court in Sarajevo against Gavrilo Princip and his comrades on account of the assassination", which allegedly demonstrated the culpability and assistance provided to the conspirators by various Serbian officials.

"[117] Jagow ordered Lichnowsky to tell Grey of the supposed German ignorance of the Austro-Hungarian ultimatum, and that Germany regarded Austro-Serbian relations as "an internal affair of Austria-Hungary, in which we had no standing to intervene".

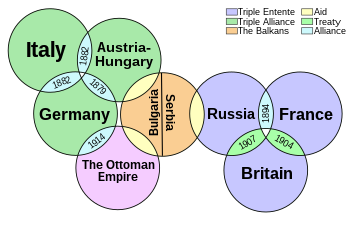

"[117] At the same time, Grey met with opposition from the Russian ambassador who warned that a conference with Germany, Italy, France, and Britain serving as the mediators between Austria-Hungary and Russia would break apart the informal Triple Entente.

[88] That same day, Grey, who was worried by the tone of the ultimatum (which he felt seemed designed to be rejected), warned Lichnowsky of the dangers of "European war à quatre" (involving Russia, Austria, France and Germany) if Austro-Hungarian troops entered Serbia.

[s] To stop a war, the Permanent Secretary of the British Foreign Office, Arthur Nicolson, suggested again that a conference be held in London chaired by Britain, Germany, Italy, and France to resolve the dispute between Austria-Hungary and Serbia.

The Russian Agriculture Minister Alexander Krivoshein, who was especially trusted by Tsar Nicholas II, argued that Russia was not militarily ready for a conflict with Germany and Austria-Hungary, and that it could achieve its objectives with a cautious approach.

[140] On 26 July, Berchtold rejected Grey's mediation offer, and wrote that if a localisation should not prove possible, then the Dual Monarchy was counting, "with gratitude", on Germany's support "if a struggle against another adversary is forced on us".

[145] On 26 July, in St. Petersburg, the German ambassador Friedrich von Pourtalès told Sazonov to reject Grey's offer of a summit in London,[126] stating that the proposed conference was "too unwieldy", and if Russia were serious about saving the peace, they would negotiate directly with the Austro-Hungarians.

[147] Philippe Berthelot, the political director of the Quai d'Orsay, told Wilhelm von Schoen, the German ambassador in Paris that "to my simple mind Germany’s attitude was inexplicable if it did not aim at war".

[149] The French Foreign Minister informed the German ambassador in Paris, Schoen, that France was anxious to find a peaceful solution, and was prepared to do his utmost with his influence in St. Petersburg if Germany should "counsel moderation in Vienna, since Serbia had fulfilled nearly every point".

[158] Jagow went on to state he was "absolutely against taking account of the British wish",[158] because "the German government point of view was that it was at the moment of the highest importance to prevent Britain from making common cause with Russia and France.

[158] Szögyény ended his telegram: "If Germany candidly told Grey that it refused to communicate England’s peace plan, that objective [ensuring British neutrality in the coming war] might not be achieved.

[ab] The Austro-Hungarian ambassador in Paris, Count Nikolaus Szécsen von Temerin, reported to Vienna: "The far-reaching compliance of Serbia, which was not regarded as possible here, has made a strong impression.

[143] At 1:00 a.m. on 29 July 1914 the first shots of the First World War were fired by the Austro-Hungarian monitor SMS Bodrog, which bombarded Belgrade in response to Serbian sappers blowing up the railway bridge over the river Sava which linked the two countries.

[183] After Goschen left the meeting, Bethmann Hollweg received a message from Prince Lichnowsky saying that Grey was most anxious for a four power conference, but that if Germany attacked France, then Britain would have no other choice but to intervene in the war.

[citation needed] In the evening of Thursday, 30 July, with Berlin's strenuous efforts to persuade Vienna to some form of negotiation, and with Bethmann Hollweg still awaiting a response from Berchtold, Russia gave the order for full mobilisation.

[179] At 9:00 p.m. on 30 July, Bethmann Hollweg gave in to Moltke and Falkenhayn's repeated demands and promised them that Germany would issue a proclamation of "imminent danger of war" at noon the next day regardless of whether Russia began a general mobilisation or not.