Forests Commission Victoria

They received valued support from Governor-General Sir Ronald Munro-Ferguson during the war years over political interference in forest management, securing adequate funding, reducing waste, expanding softwood plantations and addressing growing international concern at impending timber shortages.

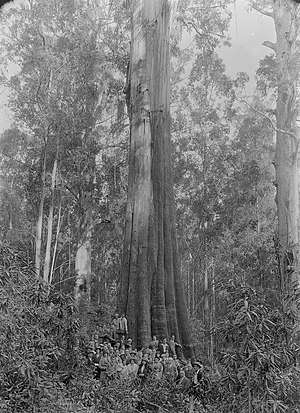

In a letter written in the Melbourne Age newspaper from Ferguson to the Assistant Commissioner of Crown Lands, Clement Hodgkinson, dated 22 February 1872 he reported trees in great number and exceptional size in the Watts River catchment but his account is often disputed as unreliable.

[30][39] The Mueller Tree[35] grew on Mount Monda north of Healesville, measured 307 feet, and was made famous after a visit in 1895 by a party including Baron Von Muller, Mr A. D. Hardy, from the State Forests and Nurseries Branch, members of the Geographical Society accompanied by renowned photographer John William Lindt[40] who also was the owner of "The Hermitage" guesthouse on the Black's Spur.

[47][48] Whether a mountain ash over 400 feet high ever existed in Victoria is now almost impossible to substantiate but the early accounts from the 1860s are still quoted in contemporary texts such as the Guinness Book of Records and Carder,[49] as well as being widely restated on the internet.

The Minister for Forests, Mr Horace Frank Richardson and a couple of the Commissioners, William James Code and Alfred Vernon Galbraith were on tour in Gippsland and were almost dangerously caught in the fires on 4 February near the Haunted Hills west of Moe.

[11] However, new controls resulted in sawmills and sleeper cutters being allocated sole rights to an area of forest to exploit but by the early 1920s this system was gradually replaced by one where royalty was paid based on the quantity of sawn timber produced.

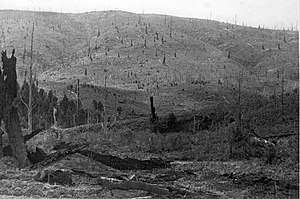

[58] By the start of the 20th century, most of the giant trees reported by Von Mueller and others were being lost to bushfires, timber splitters or clearing and efforts were mounting by local communities and conservation groups such as the Field Naturalists Club of Victoria and the ANA to set aside forests near Marysville and protect them against logging.

[59] Prominent individuals such as painter Arthur Streeton noted the "endless beauty of the green and living forest" while Professor Ernst Johannes Hartung of Melbourne University proclaimed the Valley ought to be preserved as a rare botanical and zoological sanctuary.

[15] Although revenue from timber sales declined during the Great Depression the Government channelled substantial funds to the Commission for unemployment relief works which were well suited to unskilled manual labour such as firebreak slashing, silvicultural thinning, weed spraying and rabbit control.

[15] One success story was at "Boys Camp Archived 9 August 2018 at the Wayback Machine" near Noojee which was made possible with the support of two prominent Melbourne businessmen and philanthropists, Herbert Robinson Brooks and George Richard Nicholas[61] together with the Chairman of the Forests Commission Alfred Vernon Galbraith.

Galbraith and Sir Herbert Gepp from Australian Paper Manufacturers Ltd (APM) finalised a pioneering legislated agreement which gave certain pulpwood rights to the company for fifty years over about 200,000 ha of State forest.

But World War II drew large numbers of men, led to a major escalation in Australia's heavy industry, placing urgent demands for fuel and power as well as a reduction in the supply of black coal from both New South Wales and overseas.

The assistance of an expert Advisory Panel, representing charcoal producers, manufacturers and distributors of vehicle gas equipment, the Department of Supply and Development, and the Victorian Automobile Chamber of Commerce, was enlisted under the Chairman of the Forests Commission, Alfred Vernon Galbraith.

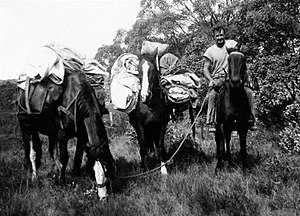

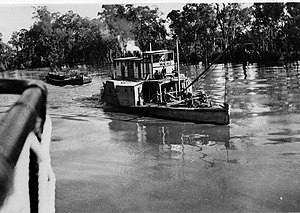

In addition to the main commodity of sawlogs and pulpwood, the Commission supplied a wide assortment of minor forest products including salt, eucalyptus oil and tea tree from the mallee deserts, wattle bark for tanneries.

Country towns then became the hub of activity, rather than the mills deeper in the forest that was characteristic of the earlier period, and settlements like Heyfield, Mansfield, Myrtleford, Orbost and Swifts Creek grew into busy centres based on the timber industry.

These included post war housing boom, the movement eastwards after the end of the 1939 fire salvage, larger sawmills situated in small country towns, rather than deep in the forest, combined with more powerful logging equipment and haulage trucks.

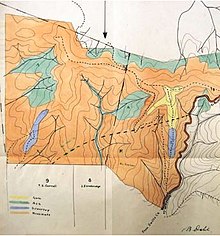

In addition to land management, conservation and fire protection the key commercial tasks involved inventory and assessment, mapping, preparing working plans, growth monitoring, calculating sustainable yield and allowable cuts, marketing and sales, licensing and approvals.

By the late 1960s regional nurseries were located at Tallangatta (Koetong), Benalla, Trentham and Rennick near Mt Gambier to produce softwood seedlings for the Commission's Plantation Extension (PX) program, Farm Forestry Agreement holders and other private land owners.

[2] History has shown that after each major bushfire, particularly if there has been a significant loss of life and property, there are loud calls from affected communities and media commentators for State and Local Governments to stop permitting land subdivision, to apply restrictive building standards and buyback high risk homes on the forest fringe.

[116] A large softwood plantation in Olinda State Forest was also burnt in 1962 and after lengthy community consultation local Commission staff and crews began replanting the area in the mid-1970s with exotic non-flammable species such as oaks and elms based on the advice of Nurseries Branch.

The State Government then established the Upper Yarra Valley and Dandenong Ranges Authority (UYVDRA) in 1976 to develop new planning schemes to assist local shires tackle the fire risk problem along with other environmental issues.

Having a good sense of direction, being able to read a map and use a measuring chain, prismatic compass and dead reckoning were essential skills, as well as a stout pair of walking boots, to somehow navigate through the bush to get back home at the end of a long day.

[123] More importantly, there was a growing recognition of the significant social and economic contribution that the Forests Commission staff, and their families, had long made simply by living in small country towns and being part of the fabric of rural society.

Along with other professionals such as school teachers, bank managers and police, foresters often volunteered for important community leadership roles in local sporting, social and civic groups such as CFA brigades or service clubs like Rotary.

Questions were also being raised over sawmill licensing levels, sustainable yield calculations, forest growth rates (MAI), wood chips and providing certainty to the timber industry as wells as contentious silvicultural techniques such as clearfelling and softwood plantation expansion dominated much of the often polarised forestry debate.

[104] Meanwhile, buoyed by their success in the Franklin Dam dispute in Tasmania in the early 1980s, groups of environmental activists later took matters into their own hands, particularly in far east Gippsland, to confront timber harvesting and mount a prolonged protest campaign and forest blockades.

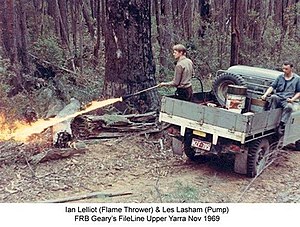

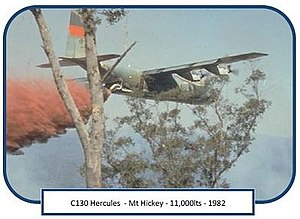

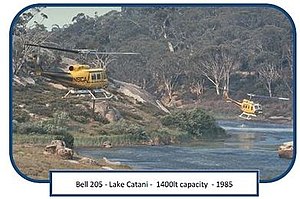

[67] These medium helicopters could also be fitted with Canadian built belly tanks, which although had a limited water bombing capacity of about 1400 litres, were still very effective in tight mountainous terrain providing close support for ground crews working near the fire edge.

The pace of change in forests management accelerated with the new State Government impatient to implement their policies and institutional reform including:[131] Also the new departmental arrangements and resources were severely tested during the summer of 1984/85 when 111 fires started from lightning in just one day.

But departmental fortunes then became increasingly tied to State political upheavals, firstly coinciding with the appointment of the new Labor Premier, Joan Kirner in August 1990 and then later when Jeff Kennett's Liberal government swept to power in October 1992.

Coupled with the cessation of a steady stream of new graduates coming from Creswick and other tertiary institutions from 1980 onwards led to shortages of experience and skills and worrying succession planning problems, particularly finding enough experienced staff to develop sound forest policy and for fire suppression.