Royal Flying Corps

Because of its potential for the 'devastation of enemy lands and the destruction of industrial and populous centres on a vast scale', he recommended a new air service be formed that would be on a level with the Army and Royal Navy.

With the growing recognition of the potential for aircraft as a cost-effective method of reconnaissance and artillery observation, the Committee of Imperial Defence established a sub-committee to examine the question of military aviation in November 1911.

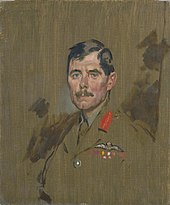

Additionally, although the Royal Flying Corps in France was never titled as a division, by March 1916 it comprised several brigades and its commander (Trenchard) had received a promotion to major-general, giving it in effect divisional status.

Each flight contained on average between six and ten pilots (and a corresponding number of observers, if applicable) with a senior sergeant and thirty-six other ranks (as fitters, riggers, metalsmiths, armourers, etc.).

[citation needed] Following Sir David Henderson's return from France to the War Office in August 1915, he submitted a scheme to the Army Council which was intended to expand the command structure of the Flying Corps.

Officers would be billeted to local country houses,[11] or commandeered châteaux when posted abroad, if suitable accommodation had not been built on the Station.

Air Stations were established in southern Ontario at the following locations: The RFC was also responsible for the manning and operation of observation balloons on the Western front.

This aggressive, if costly, doctrine did however provide the Army General Staff with vital and up-to-date intelligence on German positions and numbers through continual photographic and observational reconnaissance throughout the war.

The crew – pilot Second Lieutenant Vincent Waterfall and observer Lt. Charles George Gordon Bayly, of 5 Squadron – flying an Avro 504 over Belgium, were killed by infantry fire.

After the Great Retreat from Mons, the Corps fell back to the Marne where in September, the RFC again proved its value by identifying von Kluck's First Army's left wheel against the exposed French flank.

By late 1915, therefore, the RFC had adopted a modified version of the French cockade (or roundel) marking, with the colours reversed (the blue circle outermost).

Later in September, 1914, during the First Battle of the Aisne, the RFC made use of wireless telegraphy to assist with artillery targeting and took aerial photographs for the first time.

This led to concerns as to who had responsibility for them and in November 1916 squadron commanders had to be reminded "that it is their duty to keep in close touch with the operators attached to their command, and to make all necessary arrangements for supplying them with blankets, clothing, pay, etc" (Letter from Headquarters, 2nd Brigade RFC dated 18 November 1916 – Public Records Office AIR/1/864) The wireless operators' work was often carried out under heavy artillery fire in makeshift dug-outs.

[citation needed] The obvious potential for aerial bombardment of the enemy was not lost on the RFC, and despite the poor payload of early war aircraft, bombing missions were undertaken.

Days later, Lieutenant William Barnard Rhodes-Moorhouse of No 2 Squadron was posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross after bombing Courtrai station in a BE2c.

Aircraft were increasingly engaged in ground attack operations as the war wore on, aimed at disrupting enemy forces at or near the front line and during offensives.

Ground attack sorties were carried out at very low altitude and were often highly effective, in spite of the primitive nature of the weaponry involved, compared with later conflicts.

Although most squadrons only used Saint-Omer as a transit camp before moving on to other locations, the base grew in importance as it increased its logistic support to the RFC.

Although this belief was widely held by senior British commanders, the RFC's offensive posture resulted in the loss of many men and machines and some doubted its effectiveness.

By the end of the Somme offensive in November 1916, the RFC had lost 800 aircraft and 252 aircrew killed (all causes) since July 1916, with 292 tons of bombs dropped and 19,000 Recce photographs taken.

By the summer of 1917, the introduction of the next generation of technically advanced combat aircraft (such as the SE5, Sopwith Camel and Bristol Fighter) ensured losses fell and damage inflicted on the enemy increased.

Despite their relatively small numbers the RFC gave valuable assistance to the Army in the eventual defeat of Ottoman forces in Palestine, Trans Jordan and Mesopotamia (Iraq).

The battle reached its peak on 12 April, when the newly formed RAF dropped more bombs, and flew more missions than any other day during the war.

Because of its potential for the 'devastation of enemy lands and the destruction of industrial and populous centres on a vast scale', he recommended a new air service be formed that would be on a level with the Army and Royal Navy.

The formation of the new service would make underused RNAS resources available for the Western Front, as well as ending the inter-service rivalry that at times had adversely affected aircraft procurement.

Between April 1917 and January 1919, Camp Borden in Ontario hosted instruction on flying, wireless, air gunnery and photography, training 1,812 RFC Canada pilots and 72 for the United States.

During winter 1917–18, RFC instructors trained with the Aviation Section, US Signal Corps on three airfields in the United States accommodating about six thousand men, at Camp Taliaferro near Fort Worth, Texas.

The parachutes of the time were also heavy and cumbersome, and the added weight was frowned upon by some experienced pilots as it adversely affected aircraft with already marginal performance.

Eventually, however, public interest and the newspapers' demand for heroes led to this policy being abandoned, with the feats of aces such as Captain Albert Ball raising morale in the service as well as on the "home front".

For a short time after the formation of the RAF, pre-RAF ranks such as Lieutenant, Captain and Major continued to exist, a practice that officially ended on 15 September 1919.