Foundations of geometry

The completeness and independence of general axiomatic systems are important mathematical considerations, but there are also issues to do with the teaching of geometry which come into play.

Based on ancient Greek methods, an axiomatic system is a formal description of a way to establish the mathematical truth that flows from a fixed set of assumptions.

Euclid's axioms seemed so intuitively obvious (with the possible exception of the parallel postulate) that any theorem proved from them was deemed true in an absolute, often metaphysical, sense.

Euclid's systematic development of his subject, from a small set of axioms to deep results, and the consistency of his approach throughout the Elements, encouraged its use as a textbook for about 2,000 years.

[17] Modern attitudes towards, and viewpoints of, an axiomatic system can make it appear that Euclid was in some way sloppy or careless in his approach to the subject, but this is an ahistorical illusion.

Mathematician and historian W. W. Rouse Ball put these criticisms in perspective, remarking that "the fact that for two thousand years [the Elements] was the usual text-book on the subject raises a strong presumption that it is not unsuitable for that purpose.

[23] He does not go astray and prove erroneous things because of this, since he is making use of implicit assumptions whose validity appears to be justified by the diagrams which accompany his proofs.

[24] For example, in the first construction of Book 1, Euclid used a premise that was neither postulated nor proved: that two circles with centers at the distance of their radius will intersect in two points.

The German mathematician Moritz Pasch (1843–1930) was the first to accomplish the task of putting Euclidean geometry on a firm axiomatic footing.

[27] In his book, Vorlesungen über neuere Geometrie published in 1882, Pasch laid the foundations of the modern axiomatic method.

He originated the concept of primitive notion (which he called Kernbegriffe) and together with the axioms (Kernsätzen) he constructs a formal system which is free from any intuitive influences.

[29] The Italian mathematician Mario Pieri (1860–1913) took a different approach and considered a system in which there were only two primitive notions, that of point and of motion.

At the University of Göttingen, during the 1898–1899 winter term, the eminent German mathematician David Hilbert (1862–1943) presented a course of lectures on the foundations of geometry.

At the request of Felix Klein, Professor Hilbert was asked to write up the lecture notes for this course in time for the summer 1899 dedication ceremony of a monument to C.F.

Hilbert's axiom system is constructed with six primitive notions: point, line, plane, betweenness, lies on (containment), and congruence.

Moore independently proved that this axiom is redundant, and the former published this result in an article appearing in the Transactions of the American Mathematical Society in 1902.

In a radical departure from the synthetic approach of Hilbert, Birkhoff was the first to build the foundations of geometry on the real number system.

In 1904, George Bruce Halsted published a high school geometry text based on Hilbert's axiom set.

Saunders Mac Lane (1909–2005), a mathematician,[43] wrote a paper in 1959 in which he proposed a set of axioms for Euclidean geometry in the spirit of Birkhoff's treatment using a distance function to associate real numbers with line segments.

[42] In Mac Lane's system there are four primitive notions (undefined terms): point, distance, line and angle measure.

[46] The increased number of axioms has the pedagogical advantage of making early proofs in the development easier to follow and the use of a familiar metric permits a rapid advancement through basic material so that the more "interesting" aspects of the subject can be gotten to sooner.

[51] Although much of the New math curriculum has been drastically modified or abandoned, the geometry portion has remained relatively stable in the United States.

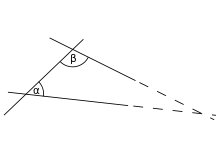

[52] Oswald Veblen (1880 – 1960) provided a new axiom system in 1904 when he replaced the concept of "betweeness", as used by Hilbert and Pasch, with a new primitive, order.

[53] Forder also gives, by combining axioms from different systems, his own treatment based on the two primitive notions of point and order.

Pieri claimed that even though he wrote in the traditional language of geometry, he was always thinking in terms of the logical notation introduced by Peano, and used that formalism to see how to prove things.

In view of the role which mathematics plays in science and implications of scientific knowledge for all of our beliefs, revolutionary changes in man's understanding of the nature of mathematics could not but mean revolutionary changes in his understanding of science, doctrines of philosophy, religious and ethical beliefs, and, in fact, all intellectual disciplines.

[57] For over two thousand years, starting in the time of Euclid, the postulates which grounded geometry were considered self-evident truths about physical space.

Circa 1813, Carl Friedrich Gauss and independently around 1818, the German professor of law Ferdinand Karl Schweikart[63] had the germinal ideas of non-Euclidean geometry worked out, but neither published any results.

Given this plenitude, one must be careful with terminology in this setting, as the term parallel line no longer has the unique meaning that it has in Euclidean geometry.

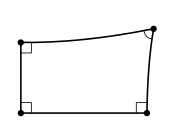

[77] There is an undefined (primitive) relation between four points, A, B, C and D denoted by (A,C|B,D) and read as "A and C separate B and D",[78] satisfying these axioms: Since the Hilbert notion of "betweeness" has been removed, terms which were defined using that concept need to be redefined.