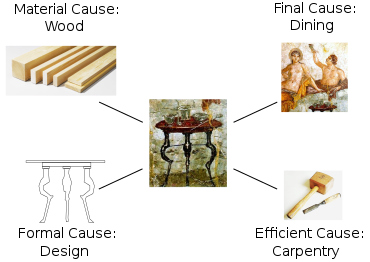

Four causes

"[1][2] While there are cases in which classifying a "cause" is difficult, or in which "causes" might merge, Aristotle held that his four "causes" provided an analytical scheme of general applicability.

[10] In his philosophical writings, Aristotle used the Greek word αἴτιον (aition), a neuter singular form of an adjective.

The Greek word had meant, perhaps originally in a "legal" context, what or who is "responsible," mostly but not always in a bad sense of "guilt" or "blame."

About a century before Aristotle, the anonymous author of the Hippocratic text On Ancient Medicine had described the essential characteristics of a cause as it is considered in medicine:[15]We must, therefore, consider the causes of each [medical] condition to be those things which are such that, when they are present, the condition necessarily occurs, but when they change to another combination, it ceases.Aristotle used the four causes to provide different answers to the question, "because of what?"

(The word "nature" for Aristotle applies to both its potential in the raw material and its ultimate finished form.

Nevertheless, he argued that simple natural bodies such as earth, fire, air, and water also showed signs of having their own innate sources of motion, change, and rest.

In this traditional terminology, 'substance' is a term of ontology, referring to really existing things; only individuals are said to be substances (subjects) in the primary sense.

[20] Like the form, this is a controversial type of explanation in science; some have argued for its survival in evolutionary biology,[21] while Ernst Mayr denied that it continued to play a role.

George Holmes Howison highlights "final causation" in presenting his theory of metaphysics, which he terms "personal idealism", and to which he invites not only man, but all (ideal) life:[30] Here, in seeing that Final Cause – causation at the call of self-posited aim or end – is the only full and genuine cause, we further see that Nature, the cosmic aggregate of phenomena and the cosmic bond of their law which in the mood of vague and inaccurate abstraction we call Force, is after all only an effect...

[31] When a match is rubbed against the side of a matchbox, the effect is not the appearance of an elephant or the sounding of a drum, but fire.

In their biosemiotic study, Stuart Kauffman, Robert K. Logan et al. (2007) remark:[34] Our language is teleological.

In The New Organon, Bacon divides knowledge into physics and metaphysics:[47] From the two kinds of axioms which have been spoken of arises a just division of philosophy and the sciences, taking the received terms (which come nearest to express the thing) in a sense agreeable to my own views.

Thus, let the investigation of forms, which are (in the eye of reason at least, and in their essential law) eternal and immutable, constitute Metaphysics; and let the investigation of the efficient cause, and of matter, and of the latent process, and the latent configuration (all of which have reference to the common and ordinary course of nature, not to her eternal and fundamental laws) constitute Physics.

And to these let there be subordinate two practical divisions: to Physics, Mechanics; to Metaphysics, what (in a purer sense of the word) I call Magic, on account of the broadness of the ways it moves in, and its greater command over nature.Explanations in terms of final causes remain common in evolutionary biology.

The latter wrote that "the most remarkable service to the philosophy of Biology rendered by Mr. Darwin is the reconciliation of Teleology and Morphology, and the explanation of the facts of both, which his view offers.

[21] Contrary to Ayala's position, Ernst Mayr states that "adaptedness... is a posteriori result rather than an a priori goal-seeking.

For example, S. H. P. Madrell writes that "the proper but cumbersome way of describing change by evolutionary adaptation [may be] substituted by shorter overtly teleological statements" for the sake of saving space, but that this "should not be taken to imply that evolution proceeds by anything other than from mutations arising by chance, with those that impart an advantage being retained by natural selection.

The validity or invalidity of such statements depends on the species and the intention of the writer as to the meaning of the phrase "in order to."

[51] Some biology courses have incorporated exercises requiring students to rephrase such sentences so that they do not read teleologically.