Fractal dimension

In mathematics, a fractal dimension is a term invoked in the science of geometry to provide a rational statistical index of complexity detail in a pattern.

It has a topological dimension of 1, but it is by no means rectifiable: the length of the curve between any two points on the Koch snowflake is infinite.

No small piece of it is line-like, but rather it is composed of an infinite number of segments joined at different angles.

[3][9] Fractal dimensions are used to characterize a broad spectrum of objects ranging from the abstract[1][3] to practical phenomena, including turbulence,[5]: 97–104 river networks,: 246–247 urban growth,[10][11] human physiology,[12][13] medicine,[9] and market trends.

[1][2][5][9][14][16] Fractal dimensions were first applied as an index characterizing complicated geometric forms for which the details seemed more important than the gross picture.

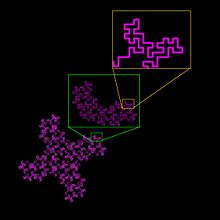

2, convoluted and space-filling, has a fractal dimension of 1.67, compared to the perceptibly less complex Koch curve in Fig.

[5] The self-similarity lies in the infinite scaling, and the detail in the defining elements of each set.

[19] Every smaller piece is composed of an infinite number of scaled segments that look exactly like the first iteration.

These are not rectifiable curves, meaning that they cannot be measured by being broken down into many segments approximating their respective lengths.

However, their fractal dimensions can be determined, which shows that both fill space more than ordinary lines but less than surfaces, and allows them to be compared in this regard.

The two fractal curves described above show a type of self-similarity that is exact with a repeating unit of detail that is readily visualized.

These include, as examples, strange attractors, for which the detail has been described as in essence, smooth portions piling up,[17]: 49 the Julia set, which can be seen to be complex swirls upon swirls, and heart rates, which are patterns of rough spikes repeated and scaled in time.

Various historical authorities credit him with also synthesizing centuries of complicated theoretical mathematics and engineering work and applying them in a new way to study complex geometries that defied description in usual linear terms.

[15][21][22] The earliest roots of what Mandelbrot synthesized as the fractal dimension have been traced clearly back to writings about nondifferentiable, infinitely self-similar functions, which are important in the mathematical definition of fractals, around the time that calculus was discovered in the mid-1600s.

[5]: 405 There was a lull in the published work on such functions for a time after that, then a renewal starting in the late 1800s with the publishing of mathematical functions and sets that are today called canonical fractals (such as the eponymous works of von Koch,[19] Sierpiński, and Julia), but at the time of their formulation were often considered antithetical mathematical "monsters".

[15][22] These works were accompanied by perhaps the most pivotal point in the development of the concept of a fractal dimension through the work of Hausdorff in the early 1900s who defined a "fractional" dimension that has come to be named after him and is frequently invoked in defining modern fractals.

[24][25] The value of D for the Koch fractal discussed above, for instance, quantifies the pattern's inherent scaling, but does not uniquely describe nor provide enough information to reconstruct it.

Many fractal structures or patterns could be constructed that have the same scaling relationship but are dramatically different from the Koch curve, as is illustrated in Fig.

Mean surface roughness, usually denoted RA, is the most commonly applied surface descriptor, however, numerous other descriptors including mean slope, root-mean-square roughness (RRMS) and others are regularly applied.

It is found, however, that many physical surface phenomena cannot readily be interpreted with reference to such descriptors, thus fractal dimension is increasingly applied to establish correlations between surface structure in terms of scaling behavior and performance.

[31] The concept of fractal dimension described in this article is a basic view of a complicated construct.

The examples discussed here were chosen for clarity, and the scaling unit and ratios were known ahead of time.

Practically, measurements of fractal dimension are affected by various methodological issues and are sensitive to numerical or experimental noise and limitations in the amount of data.

Nonetheless, the field is rapidly growing as estimated fractal dimensions for statistically self-similar phenomena may have many practical applications in various fields, including astronomy,[35] acoustics,[36][37] geology and earth sciences,[38] diagnostic imaging,[39][40][41] ecology,[42] electrochemical processes,[43] image analysis,[44][45][46][47] biology and medicine,[48][49][50] neuroscience,[51][13] network analysis, physiology,[12] physics,[52][53] and Riemann zeta zeros.

[54] Fractal dimension estimates have also been shown to correlate with Lempel–Ziv complexity in real-world data sets from psychoacoustics and neuroscience.

[51][36] An alternative to a direct measurement is considering a mathematical model that resembles formation of a real-world fractal object.

In this case, a validation can also be done by comparing other than fractal properties implied by the model, with measured data.

To describe these systems, it is convenient to speak about a distribution of fractal dimensions and, eventually, a time evolution of the latter: a process that is driven by a complex interplay between aggregation and coalescence.

, ,

, ,

, , [ 23 ]