Fractionation of carbon isotopes in oxygenic photosynthesis

The degree of carbon isotope fractionation is influenced by several factors, including the metabolism, anatomy, growth rate, and environmental conditions of the organism.

Understanding these variations in carbon fractionation across species is useful for biogeochemical studies, including the reconstruction of paleoecology, plant evolution, and the characterization of food chains.

This pathway converts inorganic carbon dioxide from the atmosphere or aquatic environment into carbohydrates, using water and energy from light, then releases molecular oxygen as a product.

The lighter isotope has a higher energy state in the quantum well of a chemical bond, allowing it to be preferentially formed into products.

The light-dependent reactions capture light energy to transfer electrons from water and convert NADP+, ADP, and inorganic phosphate into the energy-storage molecules NADPH and ATP.

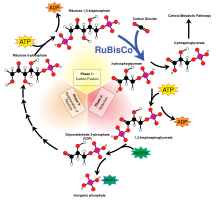

The overall general equation for the light-independent reactions is the following:[11]3 CO2 + 9 ATP + 6 NADPH + 6 H+ → C3H6O3-phosphate + 9 ADP + 8 Pi + 6 NADP+ + 3 H2OThe 3-carbon products (C3H6O3-phosphate) of the Calvin cycle are later converted to glucose or other carbohydrates such as starch, sucrose, and cellulose.

The large fractionation of 13C in photosynthesis is due to the carboxylation reaction, which is carried out by the enzyme ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase oxygenase, or RuBisCO.

[13][14] RuBisCO causes a kinetic isotope effect because 12CO2 and 13CO2 compete for the same active site and 13C has an intrinsically lower reaction rate.

[15] In addition to the discriminating effects of enzymatic reactions, the diffusion of CO2 gas to the carboxylation site within a plant cell also influences isotopic fractionation.

Such factors include the competing oxygenation reaction of RuBisCO, anatomical and temporal adaptations to enzyme activity, and variations in cell growth and geometry.

The isotope fractionations in C3 carbon fixation arise from the combined effects of CO2 gas diffusion through the stomata of the plant, and the carboxylation via RuBisCO.

[2] The wide range of variation in delta values expressed in C3 plants is modulated by the stomatal conductance, or the rate of CO2 entering, or water vapor exiting, the small pores in the epidermis of a leaf.

[1] The δ13C of C3 plants depends on the relationship between stomatal conductance and photosynthetic rate, which is a good proxy of water use efficiency in the leaf.

[19] C4 plants have developed the C4 carbon fixation pathway to conserve water loss, thus are more prevalent in hot, sunny, and dry climates.

In contrast, C3 plants directly perform the Calvin Cycle in mesophyll cells, without making use of a CO2 concentration method.

This pathway allows C4 photosynthesis to efficiently shuttle CO2 to the RuBisCO enzyme and maintain high concentrations of CO2 within bundle sheath cells.

These cells are part of the characteristic kranz leaf anatomy, which spatially separates photosynthetic cell-types in a concentric arrangement to accumulate CO2 near RuBisCO.

[21] These chemical and anatomical mechanisms improve the ability of RuBisCO to fix carbon, rather than perform its wasteful oxygenase activity.

The RuBisCO oxygenase activity, called photorespiration, causes the RuBP substrate to be lost to oxygenation, and consumes energy in doing so.

[24][25][26] Types of plants which use C4 photosynthesis include grasses and economically important crops, such as maize, sugar cane, millet, and sorghum.

This enables RuBisCO to perform catalysis while internal CO2 is sufficiently high to avoid the competing photorespiration reaction.

[1][5] However, a portion of the isotopically heavy carbon that is fixed by PEP carboxylase leaks out of the bundle sheath cells.

[4] Plants that use Crassulacean acid metabolism, also known as CAM photosynthesis, temporally separate their chemical reactions between day and night.

[28] During the night, CAM plants open stomata to allow CO2 to enter the cell and undergo fixation into organic acids that are stored in vacuoles.

This carbon is released to the Calvin cycle during the day, when stomata are closed to prevent water loss, and the light reactions can drive the necessary ATP and NADPH production.

[29] This pathway differs from C4 photosynthesis because CAM plants separate carbon by storing fixed CO2 in vesicles at night, then transporting it for use during the day.

The distribution of plants which use CAM photosynthesis includes epiphytes (e.g., orchids, bromeliads) and xerophytes (e.g., succulents, cacti).

At night, when temperature and water loss are lower, the CO2 diffuses through the stomata and produce malate via phosphenolpyruvate carboxylase.

The difference between intracellular and extracellular CO2 concentrations reflects the CO2 demand of a phytoplankton cell, which is dependent on its growth rate.

[37] More specifically, phytoplankton improve the efficiency of their primary carbon-fixing enzyme, RuBisCO, with carbon concentrating mechanisms (CCM), just as C4 plants accumulate CO2 in the bundle sheath cells.