Quantum harmonic oscillator

denotes a real number (which needs to be determined) that will specify a time-independent energy level, or eigenvalue, and the solution

[5] Then solve the differential equation representing this eigenvalue problem in the coordinate basis, for the wave function

The expectation values of position and momentum combined with variance of each variable can be derived from the wavefunction to understand the behavior of the energy eigenkets.

Second, these discrete energy levels are equally spaced, unlike in the Bohr model of the atom, or the particle in a box.

This is consistent with the classical harmonic oscillator, in which the particle spends more of its time (and is therefore more likely to be found) near the turning points, where it is moving the slowest.

Moreover, special nondispersive wave packets, with minimum uncertainty, called coherent states oscillate very much like classical objects, as illustrated in the figure; they are not eigenstates of the Hamiltonian.

The "ladder operator" method, developed by Paul Dirac, allows extraction of the energy eigenvalues without directly solving the differential equation.

Note these operators classically are exactly the generators of normalized rotation in the phase space of

In this case, subsequent applications of the lowering operator will just produce zero, instead of additional energy eigenstates.

Finally, by acting on |0⟩ with the raising operator and multiplying by suitable normalization factors, we can produce an infinite set of energy eigenstates

[12] Explicitly connecting with the previous section, the ground state |0⟩ in the position representation is determined by

The quantum harmonic oscillator possesses natural scales for length and energy, which can be used to simplify the problem.

For example, the fundamental solution (propagator) of H − i∂t, the time-dependent Schrödinger operator for this oscillator, simply boils down to the Mehler kernel,[13][14]

They are eigenvectors of the annihilation operator, not the Hamiltonian, and form an overcomplete basis which consequentially lacks orthogonality.

Since coherent states are not energy eigenstates, their time evolution is not a simple shift in wavefunction phase.

and via the Kermack-McCrae identity, the last form is equivalent to a unitary displacement operator acting on the ground state:

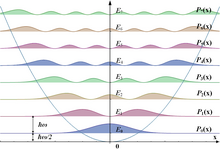

The frequency of oscillation at x is proportional to the momentum p(x) of a classical particle of energy En and position x.

Furthermore, the square of the amplitude (determining the probability density) is inversely proportional to p(x), reflecting the length of time the classical particle spends near x.

The system behavior in a small neighborhood of the turning point does not have a simple classical explanation, but can be modeled using an Airy function.

Using properties of the Airy function, one may estimate the probability of finding the particle outside the classically allowed region, to be approximately

The Wigner quasiprobability distribution for the energy eigenstate |n⟩ is, in the natural units described above,[citation needed]

By an analogous procedure to the one-dimensional case, we can then show that each of the ai and a†i operators lower and raise the energy by ℏω respectively.

There is one further difference: in the one-dimensional case, each energy level corresponds to a unique quantum state.

Formula for general N and n [gn being the dimension of the symmetric irreducible n-th power representation of the unitary group U(N)]:

The Schrödinger equation for a particle in a spherically-symmetric three-dimensional harmonic oscillator can be solved explicitly by separation of variables.

This procedure is analogous to the separation performed in the hydrogen-like atom problem, but with a different spherically symmetric potential

This result is in accordance with the dimension formula above, and amounts to the dimensionality of a symmetric representation of SU(3),[17] the relevant degeneracy group.

In analogy to the photon case when the electromagnetic field is quantised, the quantum of vibrational energy is called a phonon.

The particle-like properties of the phonon are best understood using the methods of second quantization and operator techniques described elsewhere.

, whilst the location index i (not the displacement dynamical variable) becomes the parameter x argument of the scalar field,