Franco American literature

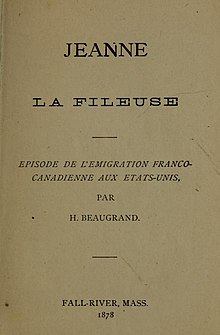

[4][10]: 34 [11] After stints as a journalist in St. Louis and New Orleans, Beaugrand founded La République in Fall River in 1875, by that time already a prominent figure in the French-Canadian cultural societies of that city.

[13] Even among many other accomplishments, including writing down the French-Canadian folk legend of La Chasse-galerie, and his Montréal mayoralty, the Dictionary of Canadian Biography has described Beaugrand's novel as "his most important work".

[12][14]: 46 In many ways the novel was also a censure of the economics of Canada, whose government Beaugrand regarded as apathetic to the causes of agriculture and industry, unnecessarily creating conditions which led to the migration to New England.

Although unremarkable in its writing style, Rémi Tremblay's autobiographical novel represents a unique account of the American Civil War as seen through the eyes of a Québécois foreign national, enlisted in the Union Army.

One of the first woman to publish a feuilleton in the genre was Anna-Marie Duval-Thibault, whose novel Les Deux Testaments was structured as a French soap opera, but sought to capture the customs of the New World.

Duval-Thibault would publish the feuilleton in her husband's Fall River newspaper L'Independente in 1888, noting in the paper's preface that the novel was inspired by a desire to contrast "the pens of French writers [which] offer us a picture of different customs unknown to most of our readers.

This effort was documented in a large tome called La Croisade Franco-Américaine ("The Franco-American Crusade") published at the end of the Congress with numerous proposals, poetry, and histories of the French-Canadians who had long embraced the identity of New Englanders.

Written in feuilleton form in 1936 for the French newspaper Le Messager of Lewiston, Maine and set in Lowell, Massachusetts, at the time of its publication, its author managed the paper's women's section "Chez-Nous".

[31] Besides its subject matter and setting, the novel is also unique in that its protagonist, Dr. Lanoie, in his dialogue, reflects on the issues of social questions in both Quebec and the United States, describing the work of medicine as literally and metaphorically "l'œuvre de reconstruction".

[34] His audience too was originally American in scope, as he had initially planned to publish the novel as a feuilleton in a Boston Haitian-American newspaper, following the establishment of a committee of Francophones between Canada and the island nation.

Dantin however saw the novel as too controversial for the time, as its subject matter concerned a black woman from the South who settles in Roxbury and falls in love with a young Frenchman who she works for as a housekeeper.

[38] A period of monolinguism emerged; while New England French endured in the regional poetry of the era,[39] the most successful Franco American novels were entirely in English and generally stood as rejections of la survivance, emphasizing a traumatic postwar acculturation.

Though of Franco origins, her famous succès de scandale, Peyton Place, did not so explicitly address a rejection of Franco-American life and values as did her 1967 novel No Adam in Eden.

[48] Though her books were successful, they were also seen as a scandal in themselves for their debaucherous and taboo themes, depicting premarital sex and adultery, standing in contrast with Catholic traditions and other works of La Survivance.

[49] While Metalious sought to distance herself from her ethnic upbringing, in recent years, her work has been embraced in the context of her heritage by groups like the Franco-American Women's Institute in Brewer, Maine.

Echoing in some ways the motifs of Ducharme's The Delusson Family, Gérard Robichaud's Papa Martel represented a departure from the melancholic overtones of the mainstream authors of this era.

A series of English-language short stories that have since been described as definitive Maine literature, Papa Martel portrays the Franco American family as accommodating, between French-Canadian Habitant culture and the assimilative influence of postwar America.

[54] Similarly, though less famous or fictional, was the 1954 As I Live and Dream by Gertrude Coté; a memoir of family history which enjoyed success in her native Maine, it was also written in English, accessible to wider audience.

[57] While the third generation of Franco-American authors had in some sense finally reached a national audience outside the trappings of literary regionalism, it had become removed from its source material, and bilingualism had, for several decades, given way solely to English.

Those who had acculturated into the American mainstream built on the legacy of the third generation in English, such as critically-acclaimed author Robert Cormier and his successful young adult novels, The Chocolate War and I Am the Cheese.

Similarly the group would also print Richard Santerre's compiled Anthologie de la littérature franco-américaine de la Nouvelle-Angleterre ("Anthology of the Franco-American Literature of New England"), which would include fictional works by Honoré Beaugrand, Louis Dantin, Rosaire Dion-Lévesque [fr], Edouard Fecteau, Camille Lessard-Bissonnette, Yvonne Le Maître, Emma Dumas, and Anna Duval-Thibault, among others.

In contrast, those who did, such as Jack Kerouac or Grace Metalious, and later Cathie Pelletier and Robert Cormier, did so as part of other literary movements— distinct from Franco American literature but clearly shaped by it.

[66][69][70][71] At the time of its publication however, Ducharme noted those at his publisher Harper, in New York City, were completely unaware of a French presence, in language or culture, in New England, despite being within a morning's drive of numerous Franco-American institutions.

In reviewing The Delusson Family in the July 1939 issue of Le Jour, Dantin would use the term "Franco-American" to frame the novel, but would also ask of author Jacques Ducharme, "has he come to the point of taking part in the intellectual life, in the literature of his adopted soil?

"[75]: 27–28 [e] And even as Ducharme was criticized as a traitor for writing his debut volume in English, he would recount pessimistically in French before a conference of the Société Historique Franco-Américaine— "Let us count our poets today.

[77] Another prominent example of overlap between the two genres also include books like Thirty Acres (Trente arpents), considered one of the most influential romans du terror ("rural novels") in Quebec literature, it is also a commentary on the industrialization of New England.

The son of its protagonist abandons the family's thirty acres of farmland to seek a new life working in textile mills in America, and ultimately expresses doubts as to the ability for such Québecois identities to remain in the country's Little Canadas, standing in contrast with the optimism of Canuck and Jeanne la Fileuse.

[74] In New England literature, the French remained excluded to a degree in a way the Irish initially were, as Catholics, and ergo outsiders not allowed into Protestant institutions for generations.

[81] In contrast Huguenot-descended New England author Sarah Orne Jewett expressed a certain solidarity with her Catholic neighbors, featuring a Franco-American family, the Bowdens, in her most notable work The Country of the Pointed Firs.

While she portrays the family as having Americanized and speaking the New England English vernacular of Maine, their customs, as well as those of Mrs. Captain Tolland in her story The Foreigner (1900) are unmistakably Catholic and Franco-American.