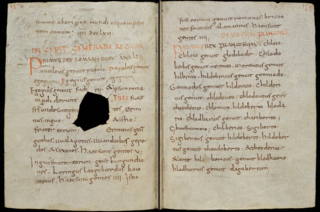

Frankish Table of Nations

The nations are the Ostrogoths, Visigoths, Vandals, Gepids, Saxons, Burgundians, Thuringians, Lombards, Bavarians, Romans, Bretons, Franks and Alamanni.

Although it survives in over ten manuscripts, the only medieval work to make use of it was the 9th-century Historia Brittonum, which nonetheless assured it a wide diffusion.

In 1851, Karl Müllenhoff assigned the text the name by which it is now generally known—Frankish Table of Nations, or fränkische Völkertafel—because he thought it was written from the perspective of a Frank of about the year 520.

[1] Georg Heinrich Pertz, in the first published notice of the text from 1824, called it Populorum Germanorum generatio ("generation of the peoples of the Germans").

[2] Müllenhoff himself, in his edition of Tacitus' Germania, included it in an appendix as the Generatio regum et gentium ("generation of kings and peoples").

[3] Bruno Krusch calls the addition to manuscript D containing the Table De gentilium et barbarorum generationibus ("on the generations of peoples and barbarians").

[4] David Dumville, in an appendix to his edition of the Historia Brittonum, calls it the Genealogiae Gentium ("genealogies of nations").

[5] Walter Goffart in his edition based on all surviving manuscripts places it under the title Generatio Gentium ("generation of peoples").

A chronicle falsely attributed to Jerome is found in manuscript F.[7] Müllenhoff dated the Table to around 520, while Krusch favoured the late 7th or early 8th century, since he believed that the list of Roman kings that accompanies the text in some manuscripts was an integral part of it and could not be earlier than the late Merovingian period.

[11] The content of the text provides evidence of a Byzantine origin, and its purpose is readily related to the interest of the emperors Justin I and Justinian I in a restoration of Roman rule in the West in the 520s.

Although there have been many past attempts to determine his ethnicity or nationality from internal evidence, the Table does not obviously glorify or denigrate any people in particular.

[11] In favour of the Byzantine hypothesis, Goffart argues that the Table represents "the ethnic panorama of the current West as seen from a metropolitan angle of vision".

[27] The texts of the Table in E and M are identical,[7] probably because M was the model for E.[21] According to Walter Pohl, the manuscripts CEM are all the product of a strategy of identity-building at Monte Cassino.

[27] It follows the generations of Noah from Genesis, of which the Table itself may be an imitation,[29] and is followed by a genealogy tracing the three brothers' descent from Adam.

[37][38] In the 12th century, Lambert of Saint-Omer incorporated the text of the Table from a copy of the Historia into his encyclopaedic Liber Floridus.

[39] Another 12th-century writer, Geoffrey of Monmouth, was also influenced by the genealogical material in the Historia, including the Frankish Table.

The Excerpta latina barbari is another originally Greek work that travelled west and survives only in a Latin translation made in the Merovingian kingdom.

[45] Inguo may be spelled Tingus or Nigueo; Istio becomes Scius or Hostius; the Gepids are sometimes Brigidos or Cybedi; the Thuringians are Loringus or Taringi; in one the Goths and Walagoths become Butes and Gualangutos.

The nations descended from Istio are the same, but Erminus' Vandals and Saxons are swapped with Inguo's Burgundians and Lombards.

[30][51] The latter may be explained as the work of a Welsh copyist for whom m and b were interchangeable,[52] but more probably reflects another modernization or updating of the Table to better reflect the reality known to a scribe working in northern Wales between 857 and 912, who would have been more familiar with the land and people of Alba (Scotland), a kingdom just forming at that time, than Alemannia.

[53][54] Patrich Wadden sets out tables displaying all the variations in the different recensions of the Historia and its Gaelic descendants.

[14] Müllenhoff once mooted that the Table was the work of a West Germanic compiler familiar with the same folk history—still thus a living tradition in the 6th century—which had informed Tacitus' account several hundred years earlier.

Possibly the author considered Germani to be synonymous with Westerners or Europeans, although the Vandals lived in Africa at the time.

It is probable that a Germanic-speaking editor in the Frankish kingdom replaced the by then rare term Visigoths with a Germanic gloss.

Procopius in On the Wars defines the Goths, Vandals, Visigoths and Gepids as the "Gothic nations" that "all came originally from one tribe".

[46] Besides the Table, Theophanes the Confessor (c. 800), Landolfus Sagax (c. 1000) and Nikephoros Kallistos (c. 1320) all preserve this quartet of nations from early Byzantine historiography.

It is possibly significant that the Table was composed shortly after the death of Clovis I (511), founder of the Merovingian Frankish kingdom when its continued cohesion was in question and its component peoples may have appeared more independent.

Willa and Gemma, the daughters of Prince Landulf IV of Benevento and Capua (r. 981–982), married prominent members of the Tuscan families Aldobrandeschi and Cadolingi.

[64] The Gaelic versions of the Table derived from the Historia drop the nations entirely, retaining only the brothers and their sons.

[65] Dumville argues that the Italian city of Alba Longa, whose inhabitants are called Albani elsewhere in the Historia, is meant.