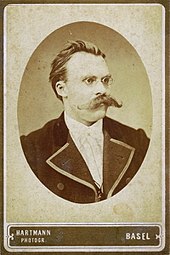

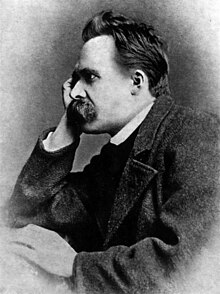

Friedrich Nietzsche

Prominent elements of his philosophy include his radical critique of truth in favour of perspectivism; a genealogical critique of religion and Christian morality and a related theory of master–slave morality; the aesthetic affirmation of life in response to both the "death of God" and the profound crisis of nihilism; the notion of Apollonian and Dionysian forces; and a characterisation of the human subject as the expression of competing wills, collectively understood as the will to power.

German conductor and pianist Hans von Bülow also described another of Nietzsche's pieces as "the most undelightful and the most anti-musical draft on musical paper that I have faced in a long time".

[26] Perhaps under Ortlepp's influence, he and a student named Richter returned to school drunk and encountered a teacher, resulting in Nietzsche's demotion from first in his class and the end of his status as a prefect.

[29] As early as his 1862 essay "Fate and History", Nietzsche had argued that historical research had discredited the central teachings of Christianity,[30] but David Strauss's Life of Jesus also seems to have had a profound effect on the young man.

Lange's descriptions of Kant's anti-materialistic philosophy, the rise of European Materialism, Europe's increased concern with science, Charles Darwin's theory of evolution, and the general rebellion against tradition and authority intrigued Nietzsche greatly.

However, in March 1868, while jumping into the saddle of his horse, Nietzsche struck his chest against the pommel and tore two muscles in his left side, leaving him exhausted and unable to walk for months.

[47][48] On returning to Basel in 1870, Nietzsche observed the establishment of the German Empire and Otto von Bismarck's subsequent policies as an outsider and with a degree of scepticism regarding their genuineness.

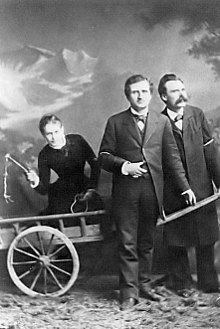

While the three spent a number of weeks together in Leipzig in October 1882, the following month Rée and Salomé left Nietzsche, leaving for Stibbe (today Zdbowo in Poland)[60] without any plans to meet again.

[61] Amidst renewed bouts of illness, living in near-isolation after a falling out with his mother and sister regarding Salomé, Nietzsche fled to Rapallo, where he wrote the first part of Also Sprach Zarathustra in only ten days.

Although Nietzsche had previously announced at the end of On the Genealogy of Morality a new work with the title The Will to Power: Attempt at a Revaluation of All Values, he seems to have abandoned this idea and, instead, used some of the draft passages to compose Twilight of the Idols and The Antichrist in 1888.

"[70] In December, Nietzsche began a correspondence with August Strindberg and thought that, short of an international breakthrough, he would attempt to buy back his older writings from the publisher and have them translated into other European languages.

[72][73] In the following few days, Nietzsche sent short writings—known as the Wahnzettel or Wahnbriefe (literally "Delusion notes" or "letters")—to a number of friends including Cosima Wagner and Jacob Burckhardt.

regard his breakdown as unrelated to his philosophy, Georges Bataille wrote poetically of his condition ("'Man incarnate' must also go mad")[83] and René Girard's postmortem psychoanalysis posits a worshipful rivalry with Richard Wagner.

"[110] Nicholas D. More states that Nietzsche's claims of having an illustrious lineage were a parody on autobiographical conventions, and suspects Ecce Homo, with its self-laudatory titles, such as "Why I Am So Wise", as being a work of satire.

In doing so, they transformed Dionysus from a figure of visceral power into a god of suffering and redemption and, in parallel, converted man from a being of flesh and instincts into a soul burdened with guilt and the need for purification.

[135] Nietzsche criticizes this Orphic reinterpretation as an early decline in Greek spiritual health, arguing that it marked the beginning of an anti-life tendency that would later manifest in Platonism and Christianity.

[150][151] Among his critique of traditional philosophy of Kant, Descartes, and Plato in Beyond Good and Evil, Nietzsche attacked the thing in itself and cogito ergo sum ("I think, therefore I am") as unfalsifiable beliefs based on naive acceptance of previous notions and fallacies.

By denying the inherent inequality of people—in success, strength, beauty, and intelligence—slaves acquired a method of escape, namely by generating new values on the basis of rejecting master morality, which frustrated them.

[168]In Ecce Homo Nietzsche called the establishment of moral systems based on a dichotomy of good and evil a "calamitous error",[169] and wished to initiate a re-evaluation of the values of the Christian world.

[171] An Israeli historian who performed a statistical analysis of everything Nietzsche wrote about Jews claims that cross-references and context make clear that 85% of the negative comments are attacks on Christian doctrine or, sarcastically, on Richard Wagner.

[181] Milne has argued against such interpretations on the grounds that such thinkers from Western and Eastern religious traditions strongly emphasise the divestment of will and the loss of ego, while Nietzsche offers a robust defence of egoism.

He wants a kind of spiritual evolution of self-awareness and overcoming of traditional views on morality and justice that stem from the superstitious beliefs still deeply rooted or related to the notion of God and Christianity.

"[citation needed] In contrast to these examples, Nietzsche's close friend Franz Overbeck recalled in his memoirs, "When he speaks frankly, the opinions he expresses about Jews go, in their severity, beyond any anti-Semitism.

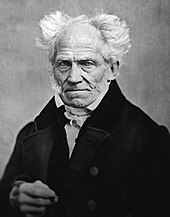

He read Kant, Plato, Mill, Schopenhauer and Spir,[217] who became the main opponents in his philosophy, and later engaged, via the work of Kuno Fischer in particular, with the thought of Baruch Spinoza, whom he saw as his "precursor" in many respects[218][219] but as a personification of the "ascetic ideal" in others.

However, Nietzsche referred to Kant as a "moral fanatic", Plato as "boring", Mill as a "blockhead", and of Spinoza, he asked: "How much of personal timidity and vulnerability does this masquerade of a sickly recluse betray?

[269][270][271] A similar notion was espoused by W. H. Auden who wrote of Nietzsche in his New Year Letter (released in 1941 in The Double Man): "O masterly debunker of our liberal fallacies ... all your life you stormed, like your English forerunner Blake.

[275] Writers and poets influenced by Nietzsche include André Gide,[276] August Strindberg,[277] Robinson Jeffers,[278] Pío Baroja,[279] D. H. Lawrence,[280] Edith Södergran[281] and Yukio Mishima.

Nietzsche has influenced philosophers such as Martin Heidegger, Jean-Paul Sartre,[333] Oswald Spengler,[334] George Grant,[335] Emil Cioran,[336] Albert Camus,[337] Ayn Rand,[338] Jacques Derrida,[339] Sarah Kofman,[340] Leo Strauss,[341] Max Scheler, Michel Foucault,[342] Bernard Williams,[343] and Nick Land.

[351] His deepening of the romantic-heroic tradition of the nineteenth century, for example, as expressed in the ideal of the "grand striver" appears in the work of thinkers from Cornelius Castoriadis to Roberto Mangabeira Unger.

[352] For Nietzsche, this grand striver overcomes obstacles, engages in epic struggles, pursues new goals, embraces recurrent novelty, and transcends existing structures and contexts.