Free Soil Party

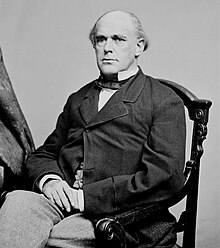

Led by Salmon P. Chase of Ohio, John P. Hale of New Hampshire, and Charles Sumner of Massachusetts, the Free Soilers strongly opposed the Compromise of 1850, which temporarily settled the issue of slavery in the Mexican Cession.

The 1854 Kansas–Nebraska Act repealed the long-standing Missouri Compromise and outraged many Northerners, contributing to the collapse of the Whigs and spurring the creation of a new, broad-based anti-slavery Republican Party.

[5] Support for the party grew in the North, especially among evangelical former Whigs in New England, upstate New York, Michigan, and Ohio's Western Reserve.

[12] To the surprise of Clay and other Whigs, the 1844 Democratic National Convention rejected Van Buren in favor of James K. Polk, and approved a platform calling for the acquisition of both Texas and Oregon Country.

[15] After a skirmish known as the Thornton Affair broke out on the northern side of the Rio Grande,[16] Polk convinced Congress to declare war against Mexico.

[18] Meanwhile, former Democratic Representative John P. Hale had defied party leaders by denouncing the annexation of Texas, causing him to lose re-election in 1845.

[23] Unlike some Northern Whigs, Wilmot and other anti-slavery Democrats were largely unconcerned by the issue of racial equality, and instead opposed the expansion of slavery because they believed the institution was detrimental to the "laboring white man.

[25] Several Northern congressmen subsequently defeated an attempt by President Polk and Senator Lewis Cass to extend the Missouri Compromise line to the Pacific.

"[37] With mix of Democratic, Whig, and Liberty Party attendees, the National Free Soil Convention convened in Buffalo early August.

Anti-slavery leaders made up a majority of the attendees, but the convention also attracted some Democrats and Whigs who were indifferent on the issue of slavery but disliked the nominee of their respective party.

[38] Salmon Chase, Preston King, and Benjamin Franklin Butler led the drafting of a platform that not only endorsed the Wilmot Proviso but also called for the abolition of slavery in Washington, D.C., and all U.S. territories.

[47] In January 1850, Senator Clay introduced a separate proposal which included the admission of California as a free state, the cession by Texas of some of its northern and western territorial claims in return for debt relief, the establishment of New Mexico and Utah territories, a ban on the importation of slaves into the District of Columbia for sale, and a more stringent fugitive slave law.

[55] Enforcement of the Fugitive Slave Act damaged Fillmore's standing among Northerners and, with the backing of Senator Seward, General Winfield Scott won the presidential nomination at the 1852 Whig National Convention.

[59] At the August 1852 Free Soil Convention, held in Pittsburgh, the party nominated a ticket consisting of Senator John P. Hale of New Hampshire and former Representative George Washington Julian of Indiana.

The party adopted a platform that called for the repeal of the Fugitive Slave Act and described slavery as "a sin against God and a crime against man.

"[60] Free Soil leaders strongly preferred Scott to Pierce, and Hale focused his campaign on winning over anti-slavery Democratic voters.

[63] Though much of this drop in support was caused by the return of Barnburners to the Democratic Party, many individuals who had voted for Van Buren in 1848 sat out the 1852 election.

[65] Hoping to spur the creation of a transcontinental railroad, in 1853 Senator Douglas proposed a bill to create an organized territorial government in a portion of the Louisiana Purchase that was north of the 36°30′ parallel, and thus excluded slavery under the terms of the Missouri Compromise.

After pro-slavery Southern senators blocked the passage of the proposal, Douglas and other Democratic leaders agreed to a bill that would repeal the Missouri Compromise and allow the inhabitants of the territories to determine the status of slavery.

[66] In response, Free Soilers issued the Appeal of the Independent Democrats, a manifesto that attacked the bill as the work of the Slave Power.

[68] The act deeply angered many Northerners, including anti-slavery Democrats and conservative Whigs who were largely apathetic towards slavery but were upset by the repeal of a thirty-year-old compromise.

Many of the larger conventions agreed to nominate a fusion ticket of candidate opposed to the Kansas–Nebraska Act, and some adopted portions of the Free Soil platform from 1848 and 1852.

Though Chase and Seward were the two most prominent members of the nascent party, the Republicans instead nominated John C. Frémont, the son-in-law of Thomas Hart Benton and a political neophyte.

[43] In New England, many trade unionists and land reformers supported the Free Soil Party, though others viewed slavery as a secondary issue or were hostile to the anti-slavery movement.

[92] In September 1851, Julian, Congressman Joshua Reed Giddings, and Lewis Tappan organized a national Free Soil convention that met in Cleveland, Ohio.

[95] The Republicans combined the Free Soil stance on slavery with Whig positions on economic issues, such as support for high tariffs and federally-funded infrastructure projects.

[103] Many of the leading Radical Republicans, including Giddings, Chase, Hale, Julian, and Sumner, had been members of the Free Soil Party.

Radical Republicans exercised an important influence during the subsequent Reconstruction era, calling for ambitious reforms designed to promote the political and economic equality of African Americans in the South.

Aside from defeating Grant, the party's central goals were the end of Reconstruction, the implementation of civil service reform, and the reduction of tariff rates.

[106] Former Free Soiler Charles Francis Adams led on several presidential ballots of the 1872 Liberal Republican convention, but was ultimately defeated by Horace Greeley.