1917 French Army mutinies

The term "mutiny" does not precisely describe events; soldiers remained in trenches and were willing to defend but refused orders to attack.

Nivelle was sacked and replaced by General Philippe Pétain, who restored morale by talking to the men, promising no more suicidal attacks, providing rest and leave for exhausted units and moderating discipline.

The catalyst for the mutinies was the extreme optimism and dashed hopes of the Nivelle offensive, pacifism (stimulated by the Russian Revolution and the trade union movement) and disappointment at the non-arrival of American troops.

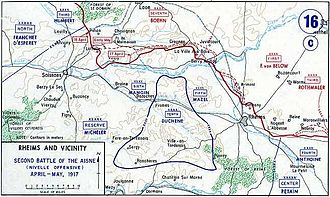

He proposed to work closely with the British Army to break through the German lines on the Western Front by a great attack against the German-occupied Chemin des Dames, a long and prominent ridge that runs east to west, just north of the Aisne River.

Nivelle applied a tactic that he had used with success at the First and Second Offensive Battles of Verdun in October and December 1916, a creeping barrage in which French artillery fired its shells to land just in front of the advancing infantry to keep the Germans under cover until they had been overrun.

News on the February Revolution in Russia was being published in French socialist newspapers and anonymous pacifist propaganda leaflets were very widely distributed.

[10] In 1967, Guy Pedroncini examined French military archives and discovered that 49 infantry divisions were destabilised and experienced episodes of mutiny.

Branches such as the heavy artillery, which was located far behind the front lines and those cavalry regiments that were still mounted, remained unaffected by the mutinies and provided detachments to round up deserters and restore order.

When an order from Russia to elect soviets was received on 16 April, the French Army whisked the Russians away from the front and moved them to central France.

[15] Along with the deterrent of military justice, Pétain offered more regular and longer leave and an end to grand offensives "until the arrival of tanks and Americans on the front".

Pétain restored morale by a combination of rest periods, frequent rotations of the front-line units and regular home furloughs.

[1] The most persistent episodes of collective indiscipline involved a relatively small number of French divisions; the mutinies did not threaten a complete military collapse.

[18] He had the support of Georges Clemenceau, who told President Woodrow Wilson in June 1917 that France planned "to wait for the Americans & meanwhile not lose more....

[20] Christopher Andrew and Kanya-Forster wrote in 1981 "Even after Petain's skilful mixture of tact and firmness had restored military discipline, the French army could only remain on the defensive and wait for the Americans".

The French government suppressed news of the mutinies to avoid alerting the Germans or harming morale on the home front.

His project had been made possible by the opening of most of the military archives, fifty years after the events, a delay that was in conformity with French War Ministry procedure.

Concurrently, that policy saved the appearance of absolute authority exercised by the Grand Quartier Général, the French high command.