French expedition to Korea

However, it did not entirely succeed in sealing itself off from foreign contact, and Catholic missionaries had shown interest in Korea as early as the 16th century with their arrival in China and Japan.

Though the Heungseon Daewongun's authority at court was not official, stemming in fact from the traditional imperative in Confucian societies for sons to obey their fathers, he quickly seized the initiative and began to control state policy.

With the aged dowager regent's blessing, the Heungseon Daewongun set out upon a dual campaign of both strengthening central authority and isolation from the disintegrating traditional order outside its borders.

By the time the Heungseon Daewongun assumed de facto control of the government in 1864, there were twelve French Jesuit priests living and preaching in Korea, and an estimated 23,000 native Korean converts.

Perhaps the most obvious was the lesson provided by China, that it had apparently reaped nothing but hardship and humiliation from its dealing with the western powers – seen most recently in its disastrous defeat during the Second Opium War.

No doubt also fresh in the Heungseon Daewongun's mind was the example of the Taiping Rebellion in China, which had been infused with Christian doctrines, and in 1858, he saw the conquest of Vietnam by the French.

An untold number of Korean Catholics also met their end (estimations run around 10,000),[11] many being executed at a place called Jeoldu-san in Seoul on the banks of the Han River.

In late June 1866, one of the three surviving French missionaries, Father Félix-Claire Ridel, managed to escape via a fishing vessel, thanks to 11 Korean converts, and made his way to Yantai, China in early July 1866.

In response to the event, the French chargé d'affaires in Beijing, Henri de Bellonet, took a number of initiatives without consulting Quai d'Orsay.

"[12]: 21 Though the French diplomatic and naval authorities in China were eager to launch an expedition, they were stymied by the almost total absence of any detailed information on Korea, including any navigational charts.

The treacherous nature of these waters, however, also convinced Roze that any movement against the fortified Korean capital with his limited numbers and large-hulled vessels was impossible.

Instead, he opted to seize and occupy Ganghwa Island, which commanded the entrance to the Han River, in the hopes of blockading the waterway to the capital during the important harvest season and thus forcing demands and reparations on the Korean court.

In Peking, the French consul Bellonet had made outrageous (and as it turned out unofficial)[citation needed] demands that the Korean monarch forfeit his crown and cede sovereignty to France.

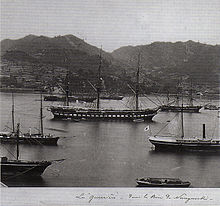

[citation needed] On 11 October, Admiral Roze left Yantai with one frigate (Guerrière), two avisos (Kien–Chan and Déroulède), two gunboats (Le Brethon and Tardif) and two corvettes (Laplace and Primauguet), as well as almost 300 Naval Fusiliers from their post in Yokohama, Japan.

[12]: 22 Roze knew it was impossible for him to lead a fleet of limited force up the treacherous and shallow Han River to the Korean capital and satisfied himself with a "coup de main" on the coast from his earlier exploratory expedition.

[14] On the mainland across the narrow channel from Ganghwa Island, however, the French offensive was met with stiff resistance from the troops of General Yi Yong-Hui, to whom Roze sent several letters asking for reparation, without success.

[20] In the course of these events, in August 1866, the U.S. civilian merchant ship, SS General Sherman foundered on the coast of Korea during an illegal trade mission.

[22] The Korean government finally agreed to open the country in 1876, when a fleet of the Imperial Japanese Navy was sent under the orders of Kuroda Kiyotaka, leading to the Treaty of Ganghwa.