French nobility

From 1808[1] to 1815 during the First Empire the Emperor Napoléon bestowed titles[2] that were recognized as a new nobility by the Charter of 4 June 1814 granted by King Louis XVIII of France.

[4][failed verification][5][6][7] However, the former authentic titles transmitted regularly can be recognized as part of the name after a request to the Department of Justice.

[14] Among the French nobility, two classes were distinguished:[9] In the 18th century, the comte de Boulainvilliers, a rural noble, posited the belief that French nobility had descended from the victorious Franks, while non-nobles descended from the conquered Gallo-Romans and subdued Germanic tribes that had also attempted to seize Gaul before the Franks, such as the Alemanni and Visigoths.

[9] Different principles of ennoblement can be distinguished: Depending on the office, the acquisition of nobility could be done in one generation or gradually over several generations: Once acquired, nobility was hereditary in the legitimate male line for all male and female descendants, with some exceptions of noblesse uterine (through the female line) recognized as valid in the provinces of Champagne and Lorraine.

[18] Wealthy families found ready opportunities to pass into the nobility: although nobility itself could not, legally, be purchased, lands to which noble rights and/or title were attached could be and often were bought by commoners who adopted use of the property's name or title and were henceforth assumed to be noble if they could find a way to be exempted from paying the taille to which only commoners were subject.

Henry IV began to enforce the law against usurpation of nobility, and in 1666–1674 Louis XIV mandated a massive program of verification.

Many documents such as notary deeds and contracts were forged, scratched or overwritten resulting in rejections by the crown officers and more fines.

[19] During the same period Louis XIV, in dire need of money for wars, issued blank letters-patent of nobility and urged crown officers to sell them to aspiring squires in the Provinces.

They were required to go to war and fight and die in the service of the king, so called impôt du sang ("blood tax").

Before Louis XIV imposed his will on the nobility, the great families of France often claimed a fundamental right to rebel against unacceptable royal abuse.

The Wars of Religion, the Fronde, the civil unrest during the minority of Charles VIII and the regencies of Anne of Austria and Marie de' Medici are all linked to these perceived loss of rights at the hand of a centralizing royal power.

Lesser families would send their children to be squires and members of these noble houses, and to learn in them the arts of court society and arms.

Economic studies of nobility in France at the end of the 18th century, reveal great differences in financial status at this time.

Guy Chaussinand-Nogaret divides the nobility of France into five distinct wealth categories, based on research into the capitation tax, which nobles were also subject to.

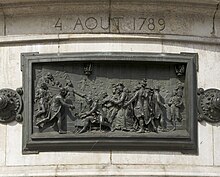

[25] At the beginning of the French Revolution, on 4 August 1789, the dozens of small dues that a commoner had to pay to the lord, such as the banalités of manorialism, were abolished by the National Constituent Assembly; noble lands were stripped of their special status as fiefs; the nobility were subjected to the same taxation as their co-nationals, and lost their privileges (the hunt, seigneurial justice, funeral honors).

[26] The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen had adopted by vote of the Assembly on 26 August 1789, but the abolition of nobility did not occur at that time.

From 1808 to 1815 during the First Empire the Emperor Napoléon bestowed titles, which the ensuing Bourbon Restoration acknowledged as a new nobility by the Charter of 4 June 1814 granted by King Louis XVIII of France.

Through contact with the Italian Renaissance and their concept of the perfect courtier (Baldassare Castiglione), the rude warrior class was remodeled into what the 17th century would come to call l'honnête homme ('the honest or upright man'), among whose chief virtues were eloquent speech, skill at dance, refinement of manners, appreciation of the arts, intellectual curiosity, wit, a spiritual or platonic attitude in love, and the ability to write poetry.

[citation needed] The château of Versailles, court ballets, noble portraits, and triumphal arches were all representations of glory and prestige.

Nobles were required to be "generous" and "magnanimous", to perform great deeds disinterestedly (i.e. because their status demanded it – whence the expression noblesse oblige – and without expecting financial or political gain), and to master their own emotions, especially fear, jealousy, and the desire for vengeance.

Nobles indebted themselves to build prestigious urban mansions (hôtels particuliers) and to buy clothes, paintings, silverware, dishes, and other furnishings befitting their rank.

[29] Conversely, social parvenus who took on the external trappings of the noble classes (such as the wearing of a sword) were severely criticised, sometimes by legal action; laws on sumptuous clothing worn by the bourgeois existed since the Middle Ages.

Traditional aristocratic values began to be criticised in the mid-17th century: Blaise Pascal, for example, offered a ferocious analysis of the spectacle of power and François de La Rochefoucauld posited that no human act – however generous it pretended to be – could be considered disinterested.

Precedence at the royal court was based on the family's ancienneté, its alliances (marriages), its hommages (dignities and offices held) and, lastly, its illustrations (record of deeds and achievements).

[31][32] Noble hierarchies were further complicated by the creation of chivalric orders – the Chevaliers du Saint-Esprit (Knights of the Holy Spirit) created by Henry III in 1578; the Ordre de Saint-Michel created by Louis XI in 1469; the Order of Saint Louis created by Louis XIV in 1696 – by official posts, and by positions in the Royal House (the Great Officers of the Crown of France), such as grand maître de la garde-robe ('grand master of the wardrobe', the royal dresser) or grand panetier (royal bread server), which had long ceased to be actual functions and had become nominal and formal positions with their own privileges.